The Cultural Evolution of Suffering

B.Contestabile First version 2007 Last version 2023

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Basics

2.1 Suffering

2.2 Cultural Evolution

3.1 Suffering as an Adaptive Trait

3.2 Non-Adaptive Suffering

3.3 Evolution without Suffering

4.1 Intensity

4.2 Quantity

4.3 Distribution

5.1 The Scientific Revolution

5.2 Technological Progress

5.3 Social Progress

5.4 Objective Progress

6. Skepticism towards Progress

6.1 The Ambivalence of Science

6.2 The Ambivalence of Technology

6.3 Social Illusions

6.4 The Threat of Human Extinction

7. Conclusion

Starting point

The level of pain increases (discontinuously) with biological evolution and seems not to be limited

(see The Biological Evolution of Pain).

Type of Problem

- Does suffering increase with cultural evolution as well as with biological evolution?

- To what extent can culture overrule the biological mechanisms?

- How will suffering end?

Result

There is no empirical data about the suffering in historical periods, but there is no doubt that the absolute number of extremely suffering people is greater than it was at any point in history until the 20th century. The number of happy people is greater as well; but suffering cannot be compensated by happiness across individuals.

At the present state of knowledge, it is impossible to foresee, if there is a technological solution to the problem of suffering [Bostrom 2005, 16]. In many areas technology works like an amplifier of the biological mechanisms. The counterproductive mechanisms of technological and social change are largely unknown or repressed. The technological improvement of welfare may have to be “paid for” by new risks. As a consequence, the historical trend could continue, but there is also a fair chance that human suffering will end by the extinction of the human species.

Starting point

The level of pain increases (discontinuously) with biological evolution and seems not to be limited

(see The Biological Evolution of Pain).

Type of Problem

- Does suffering increase with cultural evolution as well as with biological evolution?

- To what extent can culture overrule the biological mechanisms?

- How will suffering end?

Definition

Suffering is a basic affective experience of unpleasantness and aversion associated with harm or threat of harm in an individual. It constitutes the negative basis of affective states (emotions, feelings, moods, sentiments) (Suffering, Wikipedia).

Suffering and pain

- Suffering is not a mere sensation, like pain. Neither is it merely an emotion, like sadness or fear. It's a state that encompasses our whole mind that is made not just of negative emotions but also of thoughts, beliefs, and the quality of our consciousness itself (Speaking of Research, The difference between pain and suffering).

- The term suffering includes all kinds of negative experiences, such as hunger, sexual deprivation etc. whereas the term pain is often restricted to physical suffering like tissue and nerve damage.

- The concept of suffering can be applied to all sorts of areas, such as social suffering, mental suffering, existential suffering, and captures the human being as a whole person, while pain draws an especially physical reference [Stefan, 112].

For more information on pain see The Biological Evolution of Pain.

The relation between pain and suffering can be complex:

- In the Broken Heart Syndrome emotional suffering turns into pain (Broken Heart, Wikipedia)

- Persons with pain asymbolia have the conscious sensory experience of pain, but they lack the corresponding emotional experience (they do not flinch, grimace, or express distress). In masochism some kinds of pain can even be transformed into pleasure.

Assessment

Objective indirect measures

- The International Human Suffering Index relies on the statistic of the World Bank, UN and other readily available resources [Camp]. It was originally published by the Population Crisis Committee in 1987 (see Population Action International). Natural disasters are excluded in order to limit the measure to preventable suffering.

- A different index measures the suffering caused by calamities (natural and man-made disasters) and precipitous conditions out of the UNDP Human Development Report and associated data files [Anderson, 7-9].

- List of wars and anthropogenic disasters

Objective indirect measures discard the suffering caused by technological progress, including increased control, competition and unnatural ways of living. Car accidents, for example, are not included in calamities; they are in particular not included in Anderson’s “violent death rate”.

Objective direct measures

Pain intensity can now be measured from the outside, say researchers using a technique for analyzing MRI scans [Hamzelou]. Their claim reopens the debate over whether pain can be measured objectively.

Recently a method has been proposed which uses probabilistic models and machine learning to infer pain levels from sequences of physiological measures [Panaggio]. Both methods could possibly be extended to the phenomenon of suffering. But they cannot be applied in many critical situations, so that the majority of the most suffering people are excluded from the statistics.

Subjective measures

Measures for subjective happiness (e.g. the Life Satisfaction Index) can be transformed into measures for subjective suffering [Anderson, 5-6]. They can be criticized, however, on various grounds:

- Comparing the suffering of different people is an immense problem. All methods that consider suffering from an external standpoint are problematic [Stefan, 99-102]. In many cases it is even difficult to describe feelings by language. Surveys on subjective life satisfaction attempt to circumvent this problem by using point scales or percentages.

- How is it possible to know, if a person suffers? We can never unlock its inner perspective. In many cases (e.g. brain damage, young children) there is no language for communication. Even if there is a communication the investigator might be deluded by fraud or semantic differences.

- Again, the majority of the most suffering people are excluded from the statistics. People who are directly involved in accidents, wars, crimes, severe diseases, strokes, natural catastrophes etc., as well as dying people, do not participate in surveys on subjective life satisfaction.

Conclusion

We are far from a reliable measure for global suffering.

It is not even clear to what extent the different measures correlate.

Definition

Cultural evolution is an evolutionary theory of social change.

Historically, there have been a number of different approaches to the study of cultural evolution, including dual inheritance theory, sociocultural evolution, memetics, cultural evolutionism and other variants on cultural selection theory (Cultural evolution, Wikipedia).

Today most anthropologists reject 19th-century notions of progress and instead call attention to the Darwinian notion of "adaptation", arguing that all societies had to adapt to their environment in some way. A prominent example is Marvin Harris’s cultural materialism (Sociocultural evolution, Wikipedia).

Cultural evolution, in the Darwinian sense of variation and selective inheritance, could be said to trace back to Darwin himself. He argued for both customs and "inherited habits" as contributing to human evolution, grounding both in the innate capacity for acquiring language (Cultural evolution, Wikipedia).

Memetics

Richard Dawkins' 1976 book The Selfish Gene proposed the concept of the meme, which is analogous to that of the gene. A meme is an idea-replicator which can reproduce itself, by jumping from mind to mind via the process of learning from another via imitation. Along with the "virus of the mind" image, the meme might be thought of as a "unit of culture" (an idea, belief, pattern of behaviour, etc.), which spreads among the individuals of a population. The variation and selection in the copying process enables Darwinian evolution among memeplexes and therefore is a candidate for a mechanism of cultural evolution (Cultural evolution, Wikipedia).

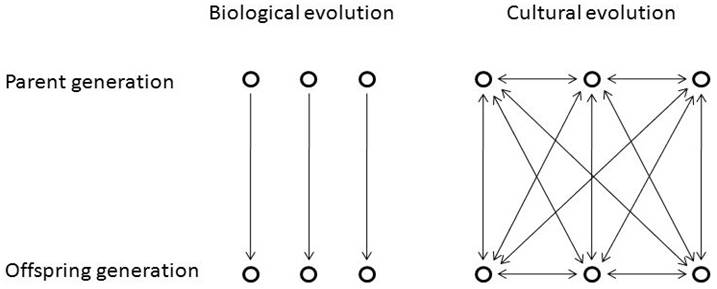

In biological evolution, the transfer of information is unidirectional and vertical, whereas in cultural evolution it is bidirectional, and vertical, horizontal or oblique – in other words, network-like [Portin]:

Random versus goal-directed evolution

Human society evolves. Change in technology, language, mortality and society is incremental, inexorable, gradual and spontaneous. It follows a narrative, going from one stage to the next; it creeps rather than jumps; it has its own spontaneous momentum rather than being driven from outside; it has no goal or end in mind; and it largely happens by trial and error – a version of natural selection [Ridley].

Is evolution a random process indeed?

On the biological level randomness is disputed. Richard Dawkins, for example, insists that although mutations may be random, evolution is not. If we look at how evolution has turned out on neighboring islands, then we see the constraints to randomness. There are only limited ways of flying and swimming, for instance, which is why wings and fins have independently evolved on many occasions; see Convergent evolution [Holmes, 2015].

Similarly, if we compare evolution in isolated cultures, we observe that there are only limited ways of managing competition and cooperation, constructing weapons, developing languages and dealing with the human condition. A concern which has independently evolved in all cultures is the desire to avoid or reduce suffering.

A conflict between biological and cultural evolution

As memes are “selfish” in that they are only “interested” in their own success, then that could well be in conflict with their biological host’s genetic interests (Cultural evolution, Wikipedia).

In this paper we focus on the conflict between the cultural interest to reduce suffering (example of a memeplex) and the biological interest to survive and reproduce (the host’s genetic interests):

- On the biological level pain has an adaptive function (see The Biological Evolution of Pain), i.e. the hedonic system serves the biological goal. The most consequent cultural implementation of this principle is Social Darwinism. But even in unsuspicious political systems the long-term success of a cultural goal may be defined by the influence it has on the genetic success of its supporters. If that is true then cultural goals serve the biological goal or they disappear. It is known, for example, that religiosity has a positive influence on the fertility rate of a population [Blume] and that the cultural criteria for human mating are strongly influenced by the biological utility function [Buss 2007].

- Nevertheless, the range of biological forces is disputed. According to Bob Holmes cultural evolution is a goal-directed activity and has even an effect on the human genome [Holmes 2013, 35]. But attempts to invert the priorities and put the reduction of suffering on top have a hard stand. Can cultural evolution ever reverse the biological trend towards a higher level of suffering? That largely depends on the role of suffering in cultural evolution.

3.1 Suffering as an Adaptive Trait

Biological mechanism

Pain is an adaptive trait if it enhances the probability of that organism to reproduce (see The Biological Evolution of Pain). Individuals with “the capability to feel pain” have a higher biological fitness than those without this capability. The importance of pain can be shown by people who suffer from analgesia. Those people have a very low life expectancy because they lack the protective function of pain [Stefan, 96].

Cultural analogue

Suffering is an adaptive trait, if it enhances the probability of that person to reproduce. Adaptive suffering informs humans about experiences that have been recognized as destructive and harmful [Stefan, 94]. It indicates limits that we, as such, do not always know beforehand. Suffering calls for changes and the urgency to get rid of it pushes us further to find solutions [Stefan, 97].

It is not uncommon that suffering is at the beginning of a process of change. And although such changes involve painful and sad experiences, they can sometimes lead to psychic and spiritual growth of human beings. So we colloquially say that we are emerging strengthened from a life crisis [Stefan, 96].

There are at least eight different functions of suffering which have a potential to improve the biological fitness:

1. Orientation function, if suffering indicates that something is wrong, has become problematic, harmful, or somehow dysfunctional.

2. Protective function, if suffering warns about a possible harm (in analogy to pain).

3. Communicative function, if the suffering of a mourning person indicates that he/she should be spared or protected.

4. Expressive function, in particular if suffering is represented in artistic forms.

5. Knowledge function, if suffering leads to discoveries and inventions.

|

Suffering precedes thinking.

[Feuerbach, 62] . |

6. Developmental function, if suffering contributes to decisive changes in lifestyle.

7. Existential-philosophical function, if suffering leads to deeper reflection.

8. Ethical function, if suffering motivates to think about one’s way of living

[Stefan, 149-152]

Paul Bloom points to the human appetites for spicy foods, hot baths, horror movies, sad songs, BDSM, and hate reading. It turns out that people often seek out pain and suffering – in pursuits such as art, ritual, sex, and sports, and in longer-term projects, such as training for a marathon or signing up to go to war. Drawing on research from developmental psychology, anthropology, and behavioral economics, Paul Bloom argues that these seemingly paradoxical choices show that we are driven by non-hedonistic goals; we revel in difficult practice, we aspire towards moral goodness, and we seek out meaningful lives. Every religious culture has explained suffering as somehow the will of God and part of the divine plan (Paul Bloom, The pleasures of suffering).

Many of these examples improve (indirectly) the biological fitness – which is the natural non-hedonistic goal. Spicy food kills food-borne bacteria and fungi; hot baths improve immunity and relieve the symptoms of cold. Horror movies prepare the psyche for real world horror, and so on.

In other cases (e.g. rituals, going to war, and moral goodness) the non-hedonistic goal is the survival of the community or culture. Evolution cannot be explained solely with mechanisms on the individual level; it also works on the group level:

Kin selection or inclusive fitness is accepted as an explanation for cooperative behavior in many species, but some behavior is difficult to explain with only this approach. In particular, it does not seem to explain the rapid rise of human civilization (Multilevel selection theory, Wikipedia).

What is commonly designated as progress in many areas is directly related to human suffering, though it is often forgotten. Many inventions have been made to facilitate the hard struggle for survival and the sufferings caused by the hard and laborious need to work. The same applies to advances in medicine. Thanks to medical achievements, many forms of suffering can be alleviated or even completely eliminated [Stefan, 96].

An obvious example for the improved biological fitness is the significant decline in preventable child deaths. Medical progress is strongly motivated by the suffering from mortality.

The adaptive role of suffering plays an important role in the long-term increase in suffering; see chapter 4. The question if technological and social progress can overrule this mechanism is discussed in chapters 5 and 6.

Biological mechanism

Some kinds of pain are not adaptive (or at least no longer directly adaptive) because natural selection is a poor designer:

1. The most discussed example is chronic pain:

Chronic pain of different causes has been characterized as a disease that affects brain structure and function. MRI studies have shown abnormal anatomical and functional connectivity, even during rest involving areas related to the processing of pain. Also, persistent pain has been shown to cause grey matter loss, which is reversible once the pain has resolved (…). People with chronic pain tend to have higher rates of depression (…). Chronic pain can contribute to decreased physical activity due to fear of making the pain worse (Chronic Pain, Wikipedia).

For information on the evolution of chronic pain see The Biological Evolution of Pain.

2. Idiopathic pain (pain that persists after the trauma or pathology has healed, or that arises without any apparent cause), may be an exception to the idea that pain is helpful to survival (Pain, Wikipedia).

3. Compromise is inherent in every biological adaptation. If a mutation offers a net reproductive advantage, it will tend to increase in frequency in a population, even if it causes vulnerability to disease [Nesse].

Cultural analogue

1. Chronic depression, as well as chronic pain affects brain structure and function. Whereas a temporary depression can be given an adaptive interpretation [Hell], chronic depression has definitively a negative effect on the patient’s biological fitness.

2. In analogy to idiopathic pain there are traumatic forms of suffering that persists after the trauma, so that the person is handicapped in his/her social life.

3. Compromise is inherent in every cultural adaptation. A higher sensitivity of the nervous system, for example, is a benefit in adapting to complex cultures. If the higher sensitivity offers a net reproductive advantage, it will tend to increase in frequency in the culture, even if it increases the probability of mental disorders.

Non-adaptive suffering without biological analogue

- One can easily realize that, just as the fear of dying soon is (biologically) functional for survival, likewise the fear of dying once (in the future) would be dysfunctional, since it would only have a paralyzing effect on the will to live [Tugendhat 2007]. The suffering from future death is a peculiarity of humans and belongs to the non-adaptive forms of suffering. The older (unconscious) parts of the brain, however, dispose of powerful mechanisms to repress the fear from future death.

- The existential-philosophical function of suffering (chapter 3.1) includes the reasoning about the causes and therapies of suffering. It is non-adaptive, if it leads to childlessness or to the retreat from social activity. Childlessness and retreat are not necessarily signs of depression; Buddhist monks, for example, just pursue a different kind of happiness.

3.3 Evolution without Suffering

Biological mechanism

The painless evolution of prokaryotes, insects etc. is the original and most probable type of evolution. A flexible brain can improve the biological fitness but it does not necessarily lead to superiority over other creatures; see The Biological Evolution of Pain.

Cultural analogue

Evolutionary Computation is a subfield of artificial intelligence which is inspired by biological evolution.

The problem-solving performance of evolutionary algorithms has advanced significantly in the past decade or so, to the extent that human-competitive results have recently been achieved in several areas of science and engineering (…). In any event the prevailing assumption that general artificial intelligence can only be (or should only be) designed by intelligent human designers is flawed and should be rejected (…). Not only should the AI systems of the future grow and learn, but their developmental and learning processes should be crafted by the most powerful designer of adaptive complexity known to science: natural selection [Spector, 1252-1253].

Efforts are underway to prevent the advancement of AI from being based on synthetic phenomenology, strictly banning all research that directly aims at or knowingly risks the emergence of artificial consciousness [Metzinger 2021]. Without consciousness there is no suffering [Metzinger 2017, 246-249].

The capability to suffer

Biological mechanism

The increasing capability to feel pain has to do with the increasing importance of learning mechanisms. The importance of learning mechanisms increases with the lifetime of the creatures and with the complexity of the environment. The behaviour of long-lived creatures is shaped by painful experiences acting on these learning mechanisms. A wide range and differentiation of emotions enhances the capability to respond to the environment. A wide range of emotions implies a high level (intensity and duration) of pain. Intensity and duration measure the importance of the event and induce a corresponding long-term storage in the memory. Under these premises the capability to feel a high level of pain is superior with regard to biological fitness (see The Biological Evolution of Pain).

Cultural analogue

Cultural evolution so far prolongs the lifetime of humans. It also adds to the complexity of the environment and increases the need for adaptation so that learning mechanisms become more important. Humans with a higher sensitivity are better equipped to master the challenges of adaptation. As a consequence, the survival value of sensitivity increases. Higher sensitivity implies the capability to experience a higher degree of suffering. As long as suffering remains an adaptive trait there is also a possibility that its intensity continues to increase [Metzinger 2021].

The infliction of suffering

Biological mechanism

There's a considerable literature on violence and cannibalism among non-human primates, and some of what goes on looks awfully like torture. Some of this has to do with enforcement of dominance hierarchies (Richard Saxton, Can animals experience sadistic glee? Ask a Biologist).

As far as the infliction of suffering has to do with the enforcement of dominance hierarchies, it could be called adaptive, because it contributes to the biological fitness of the dominant person.

Cultural analogue

As far as the history of torture is related to the enforcement of dominance hierarchies, it has a biological root. One could argue that nowadays torture is outlawed by the signers of the human rights convention (Article 5), but in practice many of these signers just outsource the dirty work. Furthermore, torture continues to exist in violent gangs (e.g. The refugee kidnapping in Sinai), in drug cartels (e.g. The Mexican drug war), in the territory of war lords (e.g. The 2014 Syrian detainee report) and – exercised by pathological individuals – in the middle of civilized communities (e.g. the report about Ian Brady).

The fact that natural selection can be a poor designer explains not only glitches like supernormal stimuli (see Pain), but also glitches in the infliction of suffering, like sadistic behavior which is not, or at least no longer directly adaptive. Culture produced (and still produces) higher degrees of suffering than nature. The biological trend towards a qualitative increase in suffering cannot be broken by culture (so far). And, because of the overall increase in population size, the absolute number of victims is greater than it was at earlier times.

The repression of suffering

Biological mechanism

From an evolutionary perspective compassion is only useful, if it serves (directly or indirectly) the proliferation of one’s genes. Beyond this context it makes sense to repress the suffering of fellow human beings.

Cultural analogue

The following asymmetry in the acceptance of suffering and happiness has been observed:

- It is more difficult to take part in other people’s suffering than to take part in other people’s joy [Smith, chapter 1, section 3].

Other people’s suffering reminds us of our own vulnerability, it pulls us down or frightens.

- Compassion and tears are considered to be a sign of weakness. Conversely happiness is interpreted as a sign of strength so that people don’t hesitate to show it [Smith, chapter 1, section 3].

In her novel The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas Ursula K. LeGuin describes a city where the good fortune of the citizens requires that an innocent child is tortured in a secret place [LeGuin]. The child stands symbolically for the innocence of extreme sufferers. The actuality of this metaphor is perplexing. Thanks to human rights organizations the Hoeryong camp, for example, was known to the world community. But the suffering of these prisoners was repressed by the majority in much the same way as the Holocaust was repressed during World War II.

Although human suffering cannot be compared to animal suffering, the Omelas metaphor also recalls the French movie Le Sang des Bêtes (The Blood of the Beasts) where peaceful scenes of Parisian suburbia contrast with scenes from a slaughterhouse. The monstrosity of animal slaughter is hidden from public view.

The repression of mortality

Biological mechanism

Just as the fear of dying soon is biologically functional for survival, likewise the fear of dying once (in the future) would be dysfunctional, since it would only have a paralyzing effect on the will to live [Tugendhat, 165].

Cultural analogue

There is a tendency to separate old, ill and dying people from the rest of society in age homes and nursing homes. Nobody wants to see the images of emaciated cancer patients and victims of stroke. The awareness of these people’s helplessness and mortality reminds us of our own vulnerability. The repression of their existence, in contrast, has a positive effect on the majority’s will and joy to live.

Overpopulation

Biological mechanism

There is a biological pressure to expand populations at the cost of the quality of life:

- Populations grow faster than resources

- Nature cares about species, not about individuals.

The expansion of sentient life is tied to an expansion of pain. Pleasure expands as well, but pain cannot be compensated by pleasure across individuals; see The Biological Evolution of Pain.

Cultural analogue

A cultural analogue to the biological mechanism was described by Thomas Malthus in his Essay on the Principle of Population and renewed by ecological thinkers like Garret Hardin and Safa Motesharrei et al. in Human and Nature Dynamics. Its validity in high-tech societies, however, is disputed, see

Although the percentage of hungry people decreases, the growing world population brings about that the absolute number of hungry people is still greater than it was at any point in history until the 20th century.

In 2013, the Food and Agriculture Organization estimated that 842 million people are undernourished (12% of the global population). Malnutrition is a cause of death for more than 3.1 million children under 5 every year. UNICEF estimates 300 million children go to bed hungry each night; and that 8000 children under the age of 5 are estimated to die of malnutrition every day (Hunger, Wikipedia).

According to the 2016 Global Hunger Index, levels of hunger are still serious or alarming in 50 countries.

According to some projections, the world population will continue to grow until at least 2050; reaching 9 billion in 2040. These projections are disputed:

- The theory of demographic transition holds that, after the standard of living and life expectancy increase, family sizes and birth rates decline. Urbanization makes children’s labor less valuable and feminism encourages woman to pursue education and careers [Bricker].

- However, as new data has become available, it has been observed that after a certain level of economic development the fertility increases again. Latest projections are 11.2 instead of 9.1 billion for 2100 [Engelman].

Depending on which estimate is used, human overpopulation may or may not have already occurred

(Wikipedia, Overpopulation).

Finally, the quantitative expansion of suffering could continue because of lifetime prolongation, space colonization and artificial suffering [Metzinger 2021], even if the world population starts to decrease.

Ecological destruction

Biological mechanism

Biological evolution is not only short-sighted, but absolutely blind with regard to the future: the design of the organisms is adapted to a "race in the here and now". Genetic reproductive success – the ultimate biological measure – is based to a large extent on efficient resource utilization [Voland, 145].

Cultural analogue

Right knowledge and right action are not the necessary result of a natural development as evolutionary epistemology and evolutionary ethics suggest. The Darwinian train is a train to nowhere [Hampe]. Ecological behavior is in the interests of the whole of humanity, but it is thwarted by an unconscious (biological) mentality of depletion [Voland, 145].

Current ecological risks concern, among others, acid oceans, fresh water, nitrogen and phosphorus cycles, land use, aerosol loading, chemical pollution, biodiversity and climate change caused by carbon dioxide technology [Pearce]:

In contrast to ozone depletion, global warming due to the so-called greenhouse effect is an environmental problem for which there is no quick fix [Rees, 108].

Power struggles and wars

Biological mechanism

- Evolution by selection has produced competitive mechanisms that function to benefit one person at the expense of others [Buss 2000].

- Human violence has a biological origin [Buss 2006] [Miles]. Killing the competition means more bounty for your own genes [Hooper]. Example: Gombe Chimpanzee War.

- The proportion of human deaths phylogenetically predicted to be caused by interpersonal violence is similar to the one phylogenetically inferred for the evolutionary ancestor of primates and apes, indicating that a certain level of lethal violence arises owing to our position within the phylogeny of mammals. It is also similar to the percentage seen in prehistoric bands and tribes, indicating that we were as lethally violent then as common mammalian evolutionary history would predict [Gomez].

Cultural analogue

Traces of human violence were found in the Jebel Sahaba Conflict, which dates back as early as 13’000 BC. The massacre at Talheim supports evidence of warfare between settlements and the massacre of Schletz shows proof of genocide ca. 5000 BC.

No utopia has ever existed. Large human societies tend to be governed by coercion. The instinct of warfare has been a driving force in nearly every civilization of the last five millennia, from ancient Mesopotamia to the British Empire [Robinson].

A possible exception is the Indus civilization that flourished from about 2600 to 1900 before BC. The Indus script, however, is not deciphered and it remains unclear, if there were battles, sacrifice, torture, and slavery as e.g. in the ancient Maya culture, which was once thought to be exceptionally peace-loving – until their hieroglyphs were deciphered [Robinson].

There are about 80 smaller ethnic groups which disapprove violence and war – for example the Semai and Batek in Malaysia, the Siriono in Bolivia, and the Piraoa in Venezuela – but they face 350 million people from indigenous groups for whom violence and war are commonplace [Husemann, 58].

For historical data about wars see:

For information about the actual situation see:

- SIPRI Yearbook: Armaments, Disarmament, and International Security

A third world war was – so far – prevented by the MAD doctrine and not by ethical progress.

Since 1945, there have been relatively few large interstate wars, especially compared to the preceding 30 years, which included both World Wars. This pattern, sometimes called the long peace, is highly controversial. Does it represent an enduring trend caused by a genuine change in the underlying conflict-generating processes? Or is it consistent with a highly variable but otherwise stable system of conflict? Using the empirical distributions of interstate war sizes and onset times from 1823 to 2003, we parameterized stationary models of conflict generation that can distinguish trends from statistical fluctuations (…). The models indicate that the postwar pattern of peace would need to endure at least another 100 to 140 years to become a statistically significant trend [Clauset 2018].

|

I don’t know with what weapons World War III will be fought. But World War IV will be fought with sticks and stones.

|

But military action is just one of many ways to enforce one’s interests at the cost of others. Oligarchies and nepotism are hard to control (even in socialism, communism and theocracies) and conspiracy theory is still alive. It is even possible that a decrease in physical violence must be “paid for” by an increase in psychological and structural forms of violence [Galtung].

In the first two decades of the 21st century only about 10% of the world population lived in full democracies. About 40% lived in flawed democracies, 15% in hybrid regimes and 35% in authoritarian regimes (Democracy-Index, Wikipedia).

Biological mechanism

Biological evolution is a process of increasing differentiation, implying increasing inequalities. Not only are the various forms of life unequal, but also the individual members within each form. Complex organisms differ more from each other than simple organisms. Evolution creates unequal distributions within all dimensions of life, including the dimensions (quality and quantity) of pain.

Cultural analogue

Cultural evolution, as well as biological evolution is a process of increasing differentiation, implying increasing inequalities. Even if the average suffering in the population decreases, higher levels may emerge in minorities. Reasons are, among others, the aberration from statistical normality and the exclusion from benefits.

Aberration from statistical normality:

For every technological and social change there are winners and losers. Undesired side-effects of cultural progress are tolerated (and reported as daily sensational news) as long as they concern a minority of the population only. Often chance decides who becomes a victim. Following some examples:

- The higher velocity in transportation tends to increase the cruelty of accidents. The more cruel the accident, the bigger the headlines.

- Economic pressure motivates people to spend organs for money or subject themselves to medical experiments. The more cruel the story, the bigger the headlines.

- In 2015 there was a refugee tragedy near Parndorf, where 71 refugees, men, women and children climbed into a refrigerated truck in Hungary and suffocated in it because the traffickers, although they heard the cries for help, did not open the door.

- In 2017 at the outbreak of a fire in the Grenfell Tower the families on the upper floors were told by telephone not to enter the stairs, to lock all doors and windows and to calm their children with the promise that rescue would arrive soon. The rescue never arrived.

This list could be extended almost infinitely.

Exclusion from benefits:

For almost every kind of suffering which is culturally defeated, there remains a fraction of the population which is excluded from the benefits. Following two examples:

1. According to anti-slavery-organizations the actual number of slaves exceeds the number of slaves that were shipped from Africa to America. From the 16th to 19th century ca. 12 million slaves were shipped across the Atlantic (Atlantic slave trade, Wikipedia). The International Labor Organization estimated that about 21 million people suffer from contemporary forms of slavery (2015). For information about slavery by nation, see Global Slavery Index, Wikipedia.

2. Discussions on extreme human suffering frequently evoke examples of torture and overlook untreated medical suffering. Unalleviated medical suffering is comparably severe to torture and significantly more common (…). I cannot find good estimates, but it is reasonable to assert that the number of people tortured every year is dwarfed by the millions dying in unmet need of palliative care. Without giving an exhaustive illustration, metastatic cancers alone slowly but surely splinter limb bones, destroy vertebrae; tear contiguous tissue, necrosis in breasts, cause severe and unremitting head pain, and more. When they are capable, some patients take their own lives or attempt to (…). In 2011, it was estimated that 5.5 billion (83%) people live in countries with low or non-existent access to adequate pain management [Sharkey].

Because of the growing world population the absolute number of extremely suffering individuals is greater than it was at any point in history until the 20th century.

The belief in progress arose in the Age of Enlightenment.

The Age of Enlightenment was an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries. The Enlightenment included a range of ideas centered on the sovereignty of reason and the evidence of the senses as the primary sources of knowledge and advanced ideals such as liberty, progress, toleration, fraternity, constitutional government and separation of church and state.

The Enlightenment emerged out of a European intellectual and scholarly movement known as Renaissance humanism (14-16th century) and the Scientific Revolution (16-17th century). French historians traditionally date its beginning with the outbreak of the French Revolution (Age of Enlightenment, Wikipedia).

The Scientific Revolution was built upon the foundation of ancient Greek learning and science in the Middle Ages, as it had been elaborated and further developed by Roman/Byzantine science (5th –15th century) and medieval Islamic science (8th –13th century). Among the most conspicuous of the revolutions was the transition from an implicit trust in the internal powers of man's mind to a professed dependence upon external observation; and from an unbounded reverence for the wisdom of the past, to a fervid expectation of change and improvement. Under the scientific method as conceived in the 17th century, systematic experimentation was slowly accepted by the scientific community (Scientific Revolution, Wikipedia).

It was assumed that the success of critical-rational thinking in science will spread out to the public sphere and that the majority will turn away from irrational (religious) arguments in ethics and political philosophy. An ethics of reason could overrule the primitive biological mechanisms (chapter 4), and finally reduce global suffering:

- Technological progress was expected to improve the quality of health care and the security of nutrition (chapter 5.2)

- Social progress should reduce, among others, the suffering from wars and social injustice (chapter 5.3).

In the following we will investigate the arguments for optimism (chapter 5) and for skepticism (chapter 6) towards the project of Enlightenment.

Empirical facts

The two most important benefits of technological progress concern the level of health care and nutrition.

Following World War II, universal health care systems began to be set up around the world. From the 1970s to the 2000s, Southern and Western European countries began introducing universal coverage, most of them building upon previous health insurance programs to cover the whole population. Beyond the 1990s, many countries in Latin America, the Caribbean, Africa, and the Asia-Pacific region, including developing countries, took steps to bring their populations under universal health coverage, including China which has the largest universal health care system in the world (Universal Health Care, Wikipedia).

World hunger is declining, thanks (in part) to technologically advanced farming and harvesting methods.

Agricultural technologies such as nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides, new seed varieties and new irrigation methods have dramatically reduced food shortages in modern times by boosting yields past previous constraints.

World Bank data shows that the percentage of the population living in households with consumption or income per person below the poverty line has decreased in each region of the world except Middle East and North Africa since 1990 (Poverty, Wikipedia):

Rapid progress has resulted in a significant decline in preventable child deaths since 1990, with the global under-5 mortality rate declining by over half between 1990 and 2016 (Child mortality, Wikipedia).

Until the middle of the 20th century, infant mortality was approximately 40–60% of the total mortality.

The following table shows the development of life expectancy since the 19th century (Life Expectancy, Wikipedia):

|

Era |

Life expectancy at birth in years |

|

19th-century world average |

28.5–32 |

|

1900 world average |

31–32 |

|

1950 world average |

45.7–48 |

|

2019–2020 world average |

72.6–73.2 |

Beliefs and speculations

The current situation is unique in history. Technological progress could eradicate suffering one day, whereas otherwise it persists or increases forever. Even if human suffering were to end by global voluntary childlessness, suffering continues to increase in other species. Humans are the only species that has at least a chance to liberate all sentient beings from suffering. If this project succeeds, then the accumulated suffering up to this point may be the least among all possible paths of evolution. Suffering could be seen as a limited, intermediary state associated with the birth of a new world, similar to the pain that goes with the birth of a child.

The technological liberation from suffering is a goal of Transhumanism and is sometimes called paradise-engineering (David Pearce). There are basically two paths to paradise:

1. The Hedonistic Imperative outlines how genetic engineering and nanotechnology will abolish suffering in all sentient life. This project is hugely ambitious but technically feasible. It is also instrumentally rational and morally urgent. The metabolic pathways of pain and malaise evolved because they served the fitness of our genes in the ancestral environment. They will be replaced by a different sort of neural architecture - a motivational system based on heritable gradients of bliss. States of sublime well-being are destined to become the genetically pre-programmed norm of mental health. It is predicted that the world's last unpleasant experience will be a precisely dateable event. Two hundred years ago, powerful synthetic pain-killers and surgical anesthetics were unknown. The notion that physical pain could be banished from most people's lives would have seemed absurd. Today most of us in the technically advanced nations take its routine absence for granted. The prospect that what we describe as psychological pain, too, could ever be banished is equally counter-intuitive. The feasibility of its abolition turns its deliberate retention into an issue of social policy and ethical choice (David Pearce, Hedonistic Imperative).

Example organization: Invincible Wellbeing's mission is to alleviate the root biological cause of pain and suffering (www.invinciblewellbeing.com)

2. Consciousness may not depend on biological substance. If this proves to be true, then the motivational system could be designed in such a way that pain is felt informational and not phenomenal. Life could then be transformed into a spiritual form free from suffering.

In both approaches there is a chance to besiege aging and death. It may be possible to replace the evolutionary adaptation thru new generations by eternally living, but permanently adapting organisms. A permanent renewal in small steps is not experienced as death.

Empirical facts

In The Better Angels of Nature Stephen Pinker argues that violence, including tribal warfare, homicide, cruel punishments, child abuse, animal cruelty, domestic violence, lynching, pogroms, and international and civil wars, has decreased over multiple scales of time and magnitude [Pinker 2011]. In Enlightenment Now he uses statistics to argue that health, prosperity, safety, peace, and happiness are on the rise, both in the West and worldwide [Pinker 2018].

- The world is not divided into rich and poor. Three quarters of all people belong to the middle-income class.

- Most governments have recognized the value of education. Illiteracy is on the decline

- In the industrialized countries social welfare systems and psychotherapies have reached a previously unknown prevalence.

- Currently there is an increasing interest in ethical issues; theoretical and applied ethics get more funds and improve in quality.

- The number and quality of charitable organizations has reached a level never seen before.

The economist Max Roser at the University of Oxford has published extensive graphics about social progress on the website "Our world in data," (https://ourworldindata.org). Most of these statistics give reason for optimism.

Evaluations

In Factfulness Hans Rosling comes to a similar conclusion and offers an explanation for pessimistic world views: Our guesses are informed by unconscious and predictable biases. It turns out that the world, for all its imperfections, is in a much better state than we might think [Rosling 2018].

Why do we have so much trouble acknowledging progress? Some of Pinker’s answers are the following:

- News media focus almost entirely on of-the-moment crises and systematically underreport positive, long-term trends

- The “availability heuristic”: People tend to estimate the probability of an event by means of “the ease with which instances come to mind”. They get the impression that mass shootings are more common than medical breakthroughs.

- The “sin of ingratitude”: We like to complain, and we don’t know much about the heroic problem-solvers of the past.

[Rothman, 27]:

Finally, there could be a fundamental psychological law, which prevents us from feeling improvements:

Many psychologists now subscribe to the “set point” theory of happiness, according to which mood is, so some extent, homeostatic: at first, our new cars, houses, or jobs make us happy, but eventually we adapt to them, returning to our “set points” and ending up roughly as happy or unhappy as we were before. Some researchers say that we run on hedonic treadmills [Rothman, 29].

Beliefs and speculations

Survival strategies conflict with strategies to combat suffering. The philosophical hopes to reduce global suffering are based on the increase in knowledge. In accordance with the philosophers of the Enlightenment, it is assumed that the success of reason in science and technology will spread out to ethics and political philosophy. The majority will turn away from irrational (religious) arguments in the context of suffering, in particular with regard to palliative care, voluntary euthanasia, population ethics, (religious) wars and social justice. Following some arguments supporting this thesis:

- The increasing complexity of the living environment asks for an increasingly intense reflection. This in turn drives behavior away from its primitive biological roots.

- The increasing lifespan implies increasing experience with suffering. Experience with suffering enforces risk-aversion. Modern societies preserve painful experiences better than historical predecessors.

- Technological progress created writing, mass literacy and finally the current information technology. Each step in this process extends social networks and, in turn, induces an extension of empathy [Rifkin].

Possibly the world community passes thru a learning process which leads to a global consensus on a high degree of risk-aversion with regard to suffering, according to the German saying “Durch Schaden wird man klug” (“Being hurt, makes you wiser”).

Stephen Jay Gould wrote in his classic book Wonderful Life: “Life is a copiously branching bush, continually pruned by the grim reaper of extinction, not a ladder of predictable progress”. He thought that humanity is just another product of contingency, far from being the pinnacle of evolution. Gould’s view has become the orthodoxy of evolutionary theory [Chorost, 35].

There is a group of theorists, however, who tries to rehabilitate the concept of evolutionary progress. They think that it will be possible to define progress in objective terms and explain why it must happen [Chorost, 36-37]. Following the main arguments against the contingency of evolution:

Eric Chaisson disclosed that evolution is characterized by growing energy rate density. He argues that energy rate density is a universal measure of the complexity of all ordered systems, from planets and stars to animals and societies. Complexity is created through the bifurcations of systems far from equilibrium, together with a generalized principle of natural selection [Ellis].

Physical, biological, and cultural evolution over 12 billion years [Chaisson, 28]

At first the growing energy rate density seems to contradict the second law of thermodynamics. The second law, however, applies only to isolated systems, and not to our universe, which is open and expanding. Energy gradients provide a loophole in the second law. Where energy gradients exist, pockets of complexity can arise even as the system as a whole decays into disorder. As a consequence local increases in complexity are not merely permitted by the second law, but required by it, and order can and does emerge spontaneously from chaos. The emergence of order from chaos is explored in synergetics (an enhancement of classical thermodynamics).

The second argument against contingency is the phenomenon of convergent evolution. Many outcomes of evolution are not accidental but inevitable. These outcomes include not just organs but brains, minds, societies, and technologies. Intelligence may be another convergent property. While primates and crows are far apart on the evolutionary tree and have very different brain structures, they have independently evolved many similar kinds of cognition, including tool use, deception and complex social groupings. A radical thesis based on this argument says that whatever catastrophe hits, the tape of life would probably run more or less the same way. It might delay the developmental process by reversing an advance, but the advance would eventually happen again. Or it might accelerate the process by opening up an environmental niche. In either case, the outcome would not change substantially; only the timing would.

Obviously, while the outcome of evolution is not fully determined, it is powerfully constrained. Direction and constraint, however, do not imply design and purpose [Chorost, 37]. A growing energy rate density does not guarantee the kind of progress that was targeted by the philosophers of the Enlightenment. In the following we investigate some of the reasons, why it is so difficult to reduce suffering on the global level.

6. Skepticism towards Progress

6.1 The Ambivalence of Science

The biological sense in life is survival and procreation, but this sense is inextricably tied to suffering and mortality (chapter 4). Religions convey sense in life by promising salvation in a spiritual world. The Scientific Revolution (16-17th century) and the Age of Enlightenment (17-18th century) destroyed religious hopes without creating an equivalent compensation (so far).

The loss of meaning

Pessimism is certainly much older than the scientific revolution but the demystification of the world in the 16th and 17th century suggested for the first time – with scientific authority – that the suffering in this world might be without a sense. Most commonly, nihilism is presented in the form of existential nihilism which argues that life is without objective meaning, purpose, or intrinsic value (Nihilism, Wikipedia)

|

Questions A man asks the waves What is the meaning of man? Whence did he come? Whither does he go? Who dwells up there on the golden stairs?

In response the waves murmur their eternal murmur, the wind blows, the clouds fly, the stars twinkle, indifferent and cold and a fool waits for an answer.

Heinrich Heine [Barash, 165]

|

Nietzsche’s God is dead was inspired by empirical sciences in the 19th century. Nietzsche replaced the metaphysical speculation about otherworlds by the scientific speculation about eternal recurrence, a controversial issue among the physicists at the time. In a revised form, the speculation is still going on. Following some recent theories, which suggest that the universe does not require a Creator:

1. Quantum theory has become the most successful, peerlessly predictive theory of basic reality ever devised. Wave functions define the quantum world in terms of probabilities and the transformation of possible states into concrete states may be a question of probabilities as well. A recent theory promoted by Daniel Sudarsky suggests that wave functions are real entities – rather than just knowledge about the quantum world – and that they collapse randomly, by themselves. Under these premises, in the early universe it was only a question of time before the wave functions of matter collapsed into an uneven distribution from which stars and galaxies could form [Cartwright].

2. The zero-energy universe hypothesis proposes that the total amount of energy in the universe is exactly zero. The theory originated in 1973, when Edward Tryon proposed in the Nature journal that the universe emerged from a large-scale quantum fluctuation of vacuum energy, resulting in its positive mass-energy being exactly balanced by its negative gravitational potential energy (Zero-energy universe, Wikipedia)

3. Pantheists like Spinoza and Einstein believed that physical laws are identical with divinity, but they imagined physical laws as something beautiful, universal and eternal. The competing vision of an absolutely contingent world emerged with the discovery that the gas laws are of a statistical nature, a discovery which inspired Alfred North Whitehead’s work in metaphysics:

Laws are observed orders of succession. This doctrine defines laws as little more than the observation of the persistence of patterns. Laws are merely ‘statistical facts. Each observed fact is a contingently new moment. There is no underlying principle of reason or a principle of causation [Dunham, 4].

The thesis that all physical laws are merely statistical facts could not be confirmed so far. On the other hand the history of physics has shown that more and more laws that seemed to be universal and eternal are in fact contingent [Scheibe]. According to Quentin Meillassoux there is truly no reason for anything:

Meillassoux claims that mathematics is what reaches the primary qualities of things as opposed to their secondary qualities as manifested in perception. He tries to show that the agnostic scepticism of those who doubt the reality of cause and effect must be transformed into a radical certainty that there is no such thing as causal necessity at all. This leads Meillassoux to proclaim that it is absolutely necessary that the laws of nature be contingent (Quentin Meillassoux, Wikipedia).

|

It takes a long time to understand nothing

Author unknown

|

The loss of paradises

The loss of faith is tied to a loss of hope, in particular the loss of a possible paradise. There are several types of paradises:

- The paradise in the Book of Genesis is a repetition of daily life without its painful conditions. It is the ideal of an agricultural society, i.e. a life undisturbed by crop failure, famine, illness and death [Hahn, 110]. Different concepts of paradises mirror different societies.

- Some paradises represent better states in the here and now, i.e. they represent memories of better times or expectations of a better future. In societies with a complex structure, the concepts can even differ within the same society. The general rule is the following: Social classes in decline glorify the past and vice-versa. The belief in progress, which is typical for the age of enlightenment, mirrors the collective advancement of the bourgeoisie; the romantic glorification of the past is the swan song of the disempowered aristocracy [Hahn, 115]. Happiness is located in a place where society hasn’t arrived yet or in a place where society was long time ago.

- The New Testament says: “No one has seen the paradise that is afforded to those who love the Lord”. This kind of paradise is abstract to an extent which makes it impossible to even attempt a falsification. On the other hand it is hardly attractive for non-philosophers and non-theologians which are deeply in sorrow about their daily life. Abstract paradises are made for religious virtuosos (Max Weber) [Hahn, 119].

All paradises have one thing in common: once they are unmasked as wishful thinking, they are lost forever.

Humiliations

Mythical gods turned (and still turn) into scientific gods who continue to humiliate people:

Freud said that there had been three great humiliations in human history (The Interpretation of Dreams, Paul Brians)

1. Galileo's discovery that we are not the center of the universe

2. Darwin's discovery that we are not the crown of creation

3. Freud’s discovery that we are not in control of our own minds.

Gerhard Vollmer describes up to nine humiliations, resulting from nine different disciplines of science [Vollmer 1994].

The philosophers of Enlightenment thought that the elimination of religious forms of guilt (sin) would be an immense relief and liberation. But knowledge soon proved to produce new forms of guilt. In a contemporary philosophical debate suffering cannot be charged to a divine creator any more, but (indirectly) to all individuals who procreate. If humans put themselves in the position of god, then the theodicy falls back on them.

|

Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.

|

The ambivalence of utopias

A utopia is a community or society possessing highly desirable or near perfect qualities. The word was coined by Sir Thomas More in Greek for his 1516 book Utopia (in Latin), describing a fictional island society in the Atlantic Ocean. The term has been used to describe both intentional communities that attempt to create an ideal society, and imagined societies portrayed in fiction (Utopia, Wikipedia)

An utopia is usually described as a goal that is hard (if not impossible) to reach: Example: Franz Hohler Die Insel Utopia (1985).

Utopias have a certain potential to replace above paradises, but they encounter a paradox: The more a utopian society improves our living conditions, the more painful death becomes. Death is bearable

- if it sets an end to suffering

- if we identify ourselves with a group and the group survives

- if we feel that we have seen whatever there is to see

All these conditions are satisfied in simple societies, but not in the current individualistic high-tech societies [Hahn, 121-124].

A hypothetical victory over death leads to paradoxical consequences as well:

- Things do not gain meaning by going on for a very long time, or even forever. Indeed, they lose it. A piece of music, a conversation, even a glance of adoration or a moment of unity have their allotted time. Too much and they become boring. An infinity and they would be intolerable." (Simon Blackburn, Wikipedia, Immortality)

- Immortality creates the risk of hell on earth, i.e. the risk of eternal suffering.

6.2 The Ambivalence of Technology

- In many areas technology works like an amplifier of the biological mechanisms, so that the ambivalence of technology can be illustrated with empirical facts (see chapter 4).

- Furthermore technological evolution, as well as biological evolution, removes certain kinds of suffering (respectively risk) and creates new forms. Following some speculations:

The prolongation of suffering

The progress in the realm of health care and nutrition is uncontested (chapter 5.2). However, if cancer, Parkinson’s disease and dementia replace death from bacterial and viral infections, then the prolongation of lifetime goes with a prolongation of suffering [Barash, 122]. The defeat of the mentioned diseases will hardly be the end of medical research and nobody knows if the trend from quickly killing diseases to long-term agonies can be broken. New forms of ecstasy create new risks of deprivation (drug withdrawal). Death becomes more threatening by the same degree, as life can be made more attractive. New technologies to prolong lifetime may be unjustly distributed and increase the suffering from early death.

Increasing complexity

In an ancestral environment risk-tolerance improved the biological fitness [Birnbacher, 37]; in a modern environment it might be fatal. New risks include, among others, nuclear technology, bio-technology and environmental risks [Leslie][Rees]:

- Access to modern technology can exert huge “leverage”. We are entering an era when a single person can, by one clandestine act, cause millions of deaths or render a city uninhabitable for years [Rees 61-63].

- It is often impossible to get “familiar” with risks because the power of contingency only reveals in a unique event:

- Technologies involving unfamiliar risks (like new weapons and genetic mutations) are often imposed by threats of war and competition. The struggle for (economic) survival explains why technological innovation accelerates even in areas of high risk.

- The undesirable side effects of new technologies are often hard to estimate because they show up with a delay. The most discussed examples of this kind are ecological destruction (chapter 4.2) and artificial intelligence (chapter 6.2).

The mentioned new risks are aspects of an increasing complexity. According to chaos theory complex systems can break down in an unpredictable way [Leslie, 6]. Examples are the Bhopal disaster and the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. The worst case, i.e. the interaction of several areas of risk may be incalculable, especially if human error, irrationality and destructive potential is involved. Interestingly the immense efforts to control complexity by means of systems theory create a new source of risk because the (imperfect or deficient) indicators and computer models are mistaken as reality [Gugerli].

Universal surveillance

The higher the risk of terror and pandemics, the more likely a restriction of privacy will be accepted by the majority. This in turn increases the risk to be controlled by dubious governments.

Universal surveillance is becoming technically feasible and could plainly be a safeguard against unwelcome clandestine activities. Techniques such as surgically implanted transmitters are already being seriously mooted to monitor criminals. If the threats escalated, we might become resigned to the need for such measures.(…) A “transparent” society in which deviant behavior couldn’t escape notice, may be accepted by its members in preference to the alternatives [Rees, 67].

Facial recognition techniques underpins China’s “sharp eyes” program, which collects surveillance footage from some fifty-five cities and will likely factor in the nation’s nascent Social Credit System. By 2020, the system will render a score for each of its 1.4 billion citizens, based on their observed behavior, down to how carefully they cross the street [Friend, 49].

Autocratic regimes could readily exploit the ways in which AIs are beginning to jar our sense of reality. AIs can generate entirely fake video synched up to real audio. Such tech could shape reality so profoundly that it would explode our bedrock faith in “seeing is believing” and hasten the advent of a full-time-surveillance / full-on-paranoia state (…) A psychopathic leader in control of a sophisticated AI portends a far greater risk in the near term than a fully autonomous AI [Friend, 49].

Human inferiority

Individuals are increasingly controlled by artificial intelligence [Revell]. And there is a growing awareness that the physical and mental capabilities of humans are stepwise surpassed and replaced by technology. Humans are in danger to be replaced by man-machine hybrids, artificial intelligence or genetically improved versions of their own species. The supersession of human intelligence by artificial intelligence (AI) may produce more losers than winners. Humans will be inferior to AI in much the same way as animals are inferior to humans [Bostrom, 2014]. Who guarantees that AI will not abuse technology? Once an AI surpasses us, there is no reason to believe it will feel grateful to us for inventing it [Friend, 44].

Max Tegmark observes that a woke AI may well find the goal of protecting us “as banal or misguided as we find compulsive reproduction.” He lays out twelve potential AI Aftermath Scenarios. Even the nominally preferable outcomes seem worse than the status quo [Friend, 51].

|

“We only have to look at ourselves to see how intelligent life might develop into something we wouldn’t want to meet.”

Stephen Hawking [Friend, 50]

|

Basic mechanisms

There are at least three mechanisms, which perpetuate suffering:

(1) Suffering can have a survival value as well as happiness; see chapter 3.1

(2) A large part of human decisions is based on unconscious motives (see An Interdisciplinary Analysis of Free Will) and the biological mechanisms described in chapter 4 still play a prominent role in the unconscious. Suffering could even continue to increase because of these mechanisms.

(3) Evaluations are decisive and not (only) empirical facts.

Following some explanations on item (3)

Empirical facts

Stephen Pinker’s claim in The Better Angels of Nature and Enlightenment Now (chapter 5.3) according to which health, prosperity, safety, peace, and happiness are on the rise, does not account for the fact that risks are on the rise as well [Goldin] [MacMillan]. The technological improvement of welfare must be “paid for” by new risks. The risks are such that social progress can be destroyed by technological disasters and dystopias (see chapter 6.2). The happiness of the current generation comes at the expense of future generations.

One of Pinker’s most persistent critics is the statistician and risk analyst Nassim Nicholas Taleb, the author of The Black Swan (…). Pinker could be right in the short term but wrong in the long term [Rothman, 30-32]

Evaluations

Hans Rosling’s claim, according to which our evaluations are informed by unconscious and pessimistic biases (chapter 5.3), is disputed. According to recent discoveries in cognitive neuroscience, the human perception – with regard to personal chances and risks – is biased in favor of optimism. The neural underpinnings and the evolutionary benefit of unrealistic optimism have been investigated by various authors [Sharot]. It is even sufficient if unrealistic optimism exists during the individual’s fecund period.

The majority of secular worldviews makes an immense effort to repress suffering and mortality [Becker] [Solomon]. The most reliable information about suffering is theoretically surveys on subjective life satisfaction. In practice, however, the most suffering persons do not participate in surveys. Furthermore, the empirical data about suffering must be distinguished from its evaluation. Interpretation can make the world look positive without manipulating the survey data. Positive utilitarianism for example – Rosling’s basis for evaluating progress (chapter 5.3) – works with unweighted averages. Unweighted averages do not consider the asymmetry between happiness and suffering and make it easy to compensate the suffering of the minority with the happiness of the majority. This principle is even more disturbing, when it comes to extreme cases of suffering beyond the assessments of economics. Because of the record high world population, the absolute number of extremely suffering people is greater than it was at any point in history until the 20th century.

- Analytical arguments against unweighted averages can be found in The Denial of the World from an Impartial View.

- Empirical arguments can be found in Is There a Predominance of Suffering?

The optimistic visions in chapter 5 contrast sharply with the pessimistic visions in chapter 6. But even if the optimistic visions prevail, there will probably always be a minority who is excluded from the benefits or affected by statistically rare misfortunes (see chapter 4.3). It is unlikely that the evolutionary mechanisms, that have tormented and destroyed minorities for thousands of years will stop doing so. The result will be an even more pronounced version of the compensation problem.

Beliefs and speculations

The majority of the world population still adheres to irrational world views (see List of religious populations). Believers of the revealed religions maintain that we are not legitimated to valuate suffering or they assume that there is an omniscient god who knows the sense of suffering and doesn’t disclose it to humans. The belief in salvation and the hope that suffering will be compensated by happiness in an ulterior world contribute to the tolerance of the world “as it is”. The best known illustration of the irreconcilable antagonism between a dogmatic and a critical rational foundation of ethics is the following passage in the Book of Genesis:

“And the Lord God commanded the man, saying: Of every tree of the garden (Eden) though mayest freely eat: But of the tree of knowledge of good and evil though shalt not eat of it: for in the day that thou eatest thereof thou shalt surely die”.

Religions (except Buddhism) tolerate all kinds of suffering which are not caused by humans. Among the successful traditions are Stoicism and Christianity. Both emphasize the divine origin of nature, and both developed in times, where little could be done to influence the course of nature. A positive attitude towards natural risks therefore improved the biological fitness [Birnbacher, 37]. The capability to glorify life and endure (natural) suffering – which was promoted and awarded in both traditions – contributed to their success.

Secular worldviews use similar strategies to make suffering acceptable. The idea that suffering makes us human, for example, is borrowed from religion [Friend, 48]. Furthermore, suffering can be seen as necessary information in the development of a better society. Suffering indicates the problems to be attacked, whereas the elimination of suffering wipes the problems under the carpet [Stefan, 161-163]. But possibly the belief in Pinker’s progress or Rosling’s progress or any kind of utopia is – similar to religious promises of salvation – just another pretext to sanction the immense suffering in this world. The suffering of the past and present is justified (again) with a speculative happiness in the future.

The battle of interpretations

To deal with the negative experiences and to legitimize the status quo every culture develops epics (myths) which describe and aestheticize the natural catastrophes and the (Dionysian) power struggles from a distant (Apollonian) perspective. The truth thus has two sides:

1. The balance of happiness and suffering with a possibly negative result [Johnson]. The fact that the majority of people adheres to a belief in progress, or to the consolations of religion, indicates that the increasing awareness of vulnerability and transience (due to accidents, diseases, age, death of close persons, etc.), is difficult to cope with. The proliferation of constructions of meaning such as the eschatology, the myth of the expulsion from paradise and the longing to retrieve it (keyword: paradise engineering) speak a clear language. Interesting is also the evaluation of the world in Hinduism and Buddhism. If the highest goal of a culture is the liberation from the cycle of rebirths, then it is obvious that this cycle has a negative connotation.

2. The ability to repress suffering and risk, aestheticize the world and construct meaning with a positive result. The positive result can, if necessary, be projected to the future by means of scenarios of progress and/or salvation. Behind the positive interpretations of the world stands the will to survive, but also the fact that epics are written by winners and revelations by "Chosen Ones". The need for positive interpretations is immense, and the people who are able to find such an interpretation get a correspondingly high reward. In view of these interests, there is reason to assume that the perception is manipulated:

The need, respectively wish to believe in something is not just an inadequate reason to believe it, but it is always and in itself – if there is no independent evidence – a counter-argument to believe it [Tugendhat 2007, 191]

Escapist and life-affirming ethics are engaged in a permanent battle of interpretations. Since this battle is driven by the deepest emotions, reason plays only a subordinate role. Even if free will exists indeed, the normative force of reason could still be grossly overestimated. The fact that religiousness correlates positively with the fertility rate of a population [Blume] makes clear that reason is a means in evolution and not an end. If reason doesn’t serve survival, it is simply dismissed, control is passed to irrational forces or the semantics of the term reasonable is modified until it complies with a strategy of survival. Suffering-averse ethics like Buddhism and Antinatalism may be justified by experience, but since they reduce or eliminate the chances to survive, its adherents take themselves out of the game (see Negative Utilitarianism and Buddhist Intuition). Compassionate, risk-averse and non-violent ethics succumbs in the competition with power-seeking, risk-tolerant and expansionist ideologies (see e.g. The Decline of Buddhism in the Indian Subcontinent). Ethical concepts are subject to the forces of evolution, as well as biological and technological concepts.

|

I don’t know why we are here, but I’m pretty sure that it is not in order to enjoy ourselves.

|

6.4 The Threat of Human Extinction

Social cycle theories

Social cycle theories suggest that cultural decay is only a matter of time.

The interpretation of history as repeating cycles of Dark and Golden Ages was a common belief among ancient cultures (…). Modern social cycle theories do not deny the presence of trend dynamics and study the interaction between cyclical and trend components. Nevertheless these theories predict civilizational collapses similar to the predictions of Oswald Spengler (Social Cycle Theory, Wikipedia).

Joseph Tainter, for example, in The Collapse of Complex Societies (1988), examines the collapse of Maya and Chacoan civilizations, and of the Western Roman Empire, in terms of network theory, energy economics and complexity theory. He thinks that the globalized modern world is subject to many of the same stresses that brought older societies to ruin (Joseph Tainter, Wikipedia).

Social cycle theories which focus on our contemporary, industrial and globalized society are known under the name collapsology. The collapse of the actual civilization could lead to human extinction (see Risk Estimations below) in contrast to the collapse of earlier civilizations. Triggers could be, for example

- asteroids or volcanic eruptions

- suicide assassins who hack autonomous weapon systems

- ecological destruction

- a hostile and superior form of (artificial) intelligence

Following some more details on these triggers:

Extinction by natural forces

An asteroid measuring over 1000 meters in diameter is potentially capable of destroying human civilization. Chances of a major asteroid impact in the 21st century are a mere 0.0002 percent, although there is a 2 percent probability of Earth colliding with a 100 meter asteroid before the year 2100 (Yury Zaitsev, Deflecting Asteroids Difficult but Possible, Space Daily)

Within the framework of NASA there is a project to deflect asteroids with a space probe (Double Asteroid Redirection Test)

Volcanic eruptions include a rare class of “super-eruptions”, thousands of times larger than the eruption of Krakatoa in 1883. A super-eruption in Toba, northern Sumatra, seventy thousand years ago left a one-hundred-kilometer crater and ejected several thousand cubic kilometers of ash, enough to have blocked out the sun for a year or more [Rees, 97]

Previous super-eruptions have been linked to mass extinction events (…). A super-eruption is 5 to 10 times more likely than an asteroid strike. At least one super-volcano explodes every 100’000 years or so, the geological record suggests [Ravilious, 32].

Intentional extinction

Philosophers who identify the human race or the mechanisms of life as the cause of suffering may develop a wish to terminate humanity or life as whole. The first promoter of an intentional extinction was Eduard von Hartmann (1842-1906):

In The Self-Destruction of Christianity and the Religion of the Future (1874), Hartman predicts that humanity will come to a collective realization of the futility of their atheistic fates, and choose to bring about their collective annihilation (Investigating Atheism, University of Cambridge).

It is known that Hartmann used far eastern sources. But the old Indian philosophers, despite of their belief in the inseparable connection between life and suffering, never considered a global intentional annihilation of humanity as an option.