Short History of Welfare Economics

B.Contestabile First version 2009 Last version 2022

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Classical Economics (18th and 19th Century)

2.1 Definition

2.2 Classical Utilitarianism

2.3 Criticism of Capitalism

3. Neoclassical Economics (since ca.1870)

3.1 Basics

3.2 Old Welfare Economics

3.3 New Welfare Economics

3.4 Social Choice Theory

3.5 Micro- and Macroeconomics

3.6 Neoclassical Synthesis

4. Modern Development Economics (since ca.1950)

4.1 Definition

4.2 Neoclassical Theory

4.3 Capability Approach

5. Happiness Economics (since ca.2005)

5.1 Basics

5.2 Criticism of Neoclassical Economics

5.3 Subjective versus Objective Data

6. On the Philosophy of Economics

6.1 Positive Economics

6.2 Normative Economics

7. Conclusion

Starting point

The term welfare economics will be treated as a synonym for normative economics in this paper (Stanford). It cannot be separated from questions about justice.

Classical utilitarianism started with the slogan “The greatest happiness for the greatest number”.

Its promoters assumed that happiness correlates with economic welfare. Traditional approximations are

- Income for the welfare of the individual

- GDP (calculated by the income approach) for the welfare of society.

Type of problem

Richard A.Easterlin, professor of economics at the University of Southern California found, as expected by most economists, that, within a given country, people with higher incomes are more likely to report being happy. However, in international comparisons, the average reported level of happiness does not vary much with national income (GNI) per person, at least for countries with income sufficient to meet basic needs (Easterlin Paradox, Wikipedia).

Does welfare economics contribute to happiness?

Result

The history of welfare economics seems to confirm the following suspicion:

The mathematical maximization of welfare is extremely useful – as a form of employment for economists (author unknown).

Whereas many branches and techniques of economics are indispensable, the mathematical maximization of welfare cannot live up to its promise:

- The assumption that happiness correlates with economic welfare is only half the truth.

- The assumptions used in the mathematical models are partly flawed.

Newer strategies have given up the idea to derive happiness exclusively from economic welfare.

The Capability Approach emphasizes that – once a decent level of economic welfare is reached – human rights become a major determinant of happiness.

Happiness Economics builds on empirical data about individual happiness instead of mathematical functions and bureaucratic indicators like the GDP and GNI.

With regard to economic welfare the hope rests on simulation models, which forecast the outcome of competing economic policies. Unfortunately, however, these models did not foresee the worst economic crises since the Great Depression.

Starting point

The term welfare economics will be used as a synonym for normative economics in this paper (Stanford). It cannot be separated from questions about justice.

Classical utilitarianism started with the slogan “The greatest happiness for the greatest number”.

Its promoters assumed that happiness correlates with economic welfare. Traditional approximations are

- Income for the welfare of the individual

- GDP (calculated by the income approach) for the welfare of society.

Type of problem

Richard A.Easterlin, professor of economics at the University of Southern California found, as expected by most economists, that, within a given country, people with higher incomes are more likely to report being happy. However, in international comparisons, the average reported level of happiness does not vary much with national income (GNI) per person, at least for countries with income sufficient to meet basic needs (Easterlin Paradox, Wikipedia).

Does welfare economics contribute to happiness?

2. Classical Economics (18th and 19th Century)

The historical context of classical economics was the age of enlightenment, the French Revolution (1789-1799) and the industrial revolution.

- Classical economics is widely regarded as the first modern school of economic thought. It is the idea that free markets can regulate themselves. Its major developers include Adam Smith (1723-1790), Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832), David Ricardo (1772-1823), Thomas Malthus (1766-1834) and John Stuart Mill (1806-1873). Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations in 1776 is usually considered to mark the beginning of classical economics. The school was active into the mid 19th century and was followed by neoclassical economics in Britain beginning around 1870.

- Classical economists attempted and partially succeeded to explain economic growth and development. They produced their "magnificent dynamics" during a period in which capitalism was emerging from a past feudal society and in which the industrial revolution was leading to vast changes in society. These changes also raised the question of how a society could be organized around a system in which every individual sought his or her own (monetary) gain.

- Classical economists reoriented economics away from an analysis of the ruler's personal interests to a class-based interest. Physiocrat Francois Quesnay and Adam Smith, for example, identified the wealth of a nation with the yearly national income, instead of the king's treasury. Smith saw this income as produced by labor applied to land and capital equipment. Once land and capital equipment are appropriated by individuals, the national income is divided up between laborers, landlords, and capitalists in the form of wages, rent, and interest.

(Classical economics, Wikipedia)

Various theories attempted to explain the formation of prices:

- Adam Smith's natural prices of commodities are the sum of the natural rates of wages, rent and interest (profits) that must be paid for inputs into production.

- David Ricardo mixed this cost-of-production theory of prices with the labor theory of value. This is the theory that prices tend toward proportionality to the labor embodied in a commodity.

- Michał Kalecki distinguished between sectors with cost-determined prices (such as manufacturing and services) and those with demand-determined prices (such as agriculture and raw material extraction).

(Cost-of-production theory of value, Wikipedia)

- A notable current within classical economics was underconsumption theory, as advanced by the Birmingham School and Thomas Robert Malthus in the early 19th century. These argued for government action to mitigate unemployment and economic downturns, and were an intellectual predecessor of what later became Keynesian economics in the 1930s.

- Another notable school was Manchester capitalism, which advocated free trade, against the previous policy of mercantilism

(History of economic thought, Wikipedia).

The designation of Smith, Ricardo and some earlier economists as "classical" is due to Karl Marx, to distinguish the "greats" of economic theory from their "vulgar" successors (Classical Economics, Wikipedia).

Origin

Historically utilitarianism was inspired by Stoicism and Epicureanism [Kolm]. The ancient Stoic vision of a mystic unity still shines up in the slogan “Reclaiming Morality from Mysticism” (Felicifia).

An early precursor of utilitarianism was the British moralist Francis Hutcheson (1694–1746).

With Francis Hutcheson the criterion of right action is its tendency to promote the general welfare of mankind. He thus anticipates Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarianism not only in principle, but even in the use of the phrase "the greatest happiness for the greatest number" (Francis Hutcheson, Wikipedia).

The classical utilitarians Jeremy Bentham (1748-1832) and John Stuart Mill (1806-1873) were concerned with legal and social reform. If anything could be identified as the fundamental motivation behind the development of classical utilitarianism it would be the desire to see useless, corrupt laws and social practices changed (History of Utilitarianism, Stanford).

Bentham’s utilitarianism

Bentham’s utilitarianism is based on the following assumptions:

1. Each individual knows best what is good for him/her

2. Each individual should decide him/herself in private matters

3. The welfare of an individual does not depend on other individual’s welfare

4. The welfare of each individual can be added in order to evaluate the total welfare of the society.

5. Each individual has the same weight (rights) in collective decisions.

6. Utility is interpersonally comparable

7. The principle of competition increases welfare, if applied under the conditions of equal opportunity.

8. Economic welfare correlates with general welfare.

9. Utility can be measured by cardinal numbers and utility functions are linear.

[Kleinewefers, 37-38]

Utilitarianism was originally developed as a challenge to the status quo. The demand that everyone count for one was anathema to the elitist society of Victorian Britain (Utilitarianism, Wikipedia).

Welfare function according to Bentham

In classical utilitarianism utility is a function of consumption. Consumption is measured in terms of preferences for (economic) goods and services. Utility is associated with the happiness which is created by consumption [Bentham, 120].

Let’s assume the society consists of two persons P1 and P2, who dispose of two goods G1 and G2. The welfare function according to Bentham would look as follows:

1. Social welfare (W) is the total of the two individual utilities (U): W = U1 + U2

2. The utility functions are identical for both persons. It is assumed that the utility (usefulness) of the two goods is the same for both persons.

3. The utility depends linearly (factors a1, a2) on the quantities (q) of the goods.

U1 = (a1 x q11) + (a2 x q12)

U2 = (a1 x q21) + (a2 x q22)

where q12 = the quantity of good G2, consumed by person P1.

Under these premises social welfare should increase linearly with the Gross National Product (GNP).

[Kleinewefers, 40]

Bentham proposed an algorithm for calculating the amount of happiness that a specific action (like consuming a good or a service) is likely to cause, the so-called Felicific calculus. This algorithm never gained practical relevance and Bentham’s utilitarian project was eventually abandoned because utility was deemed impossible to measure. Since Bentham’s time, however, the social sciences have developed greatly, and armed with more sophisticated methods, 2002 Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman and his co-workers have proposed that we go ‘back to Bentham’ [Read].

Liberalism

The development into maturity of classical liberalism took place before and after the French Revolution in Britain, and was based on the following core concepts: classical economics, free trade, laissez-faire government with minimal intervention and taxation and a balanced budget. Classical liberals were committed to individualism, liberty and equal rights. The primary intellectual influences on 19th century liberal trends were those of Adam Smith and the classical economists, Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill (Liberalism, Wikipedia)

There is, however, a profound difference between liberalism and utilitarianism:

- Utilitarianism attempts to increase the total utility of the community. The individual is subordinated to this goal.

- Liberalism claims that individual actions are only restricted by the condition not to harm others.

How could Mill claim that liberalism is compatible with utilitarianism?

The key for compatibility lies in Mills interpretation of utility [Schefczyk]:

- Mill stands in the tradition of Epicurus and Bentham according to which happiness (respectively the absence of suffering) is the only rational goal of human behavior. Mill’s innovation was to introduce a ranking for different kinds of happiness. The ranking is justified by competence, i.e. by the judgment of experienced persons. The judgment if football is preferable to the opera can only be made by persons who made a positive experience with both kinds of events. People who don’t enjoy the opera (or don’t even know it) cannot morally valuate the corresponding kind of happiness; they lack a specific perception, respectively knowledge.

- Even if all competent persons accord in ranking pleasures then this ranking is still not generally relevant. The life of an individual cannot be improved by imposing an “official” ranking upon him/her.

- Most philosophers agree that the life of an unhappy human is preferable to the life of a happy pig. But Mill doesn’t conclude that we should invest all our energy in top-quality actions. All kinds of happiness reach a point of satiation and we should therefore attempt to diversify our engagements.

The liberal characteristics of Mill’s concept can be summarized as follows [Schefczyk]:

- Tolerance, accept that perception and experiences are different

- Informality

- The denial of external and internal perfectionism

On this basis Mill claims that liberty is a consequence of the utilitarian goal. Since humans are different, the pressure for conformity and the denial of individual liberty contradicts the interests of all humans. The point in Mill’s argument consists in not only seeing other people as competitors but also as enrichment. Diversified experiences produce empirical data about possible kinds of happiness. The ethical ideal according to Mill is not restricted to tolerance, it is open and affirmative; a liberal is willing to learn and profit from other person’s experiences.

Karl Marx

The main critic of capitalism was Karl Marx (1818-1883), who saw himself as the culmination of classical economics [Brewer, 371].

- Communism emerged in response to the miserable living and working conditions of the working class in the new industrial era. The economic and political theory published in The Communist Manifesto (1848) and Das Kapital (1867) combined with the dialectic theory of history inspired by Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) provide a revolutionary critique of nineteenth-century capitalism.

- Marx developed a theory of business cycles based on exploitation, alienation, capital accumulation and economic growth (see Marxian Economics). With every boom and bust, with every capitalist crisis, thought Marx, tension and conflict between the increasingly polarized classes of capitalists and workers would heighten. Ultimately, led by the Communist party, Marx envisaged a revolution and the creation of a classless society.

In 1917 Russia crumbled into revolution led by Vladimir Lenin. Lenin promoted Marxist theory and collectivized the means of production (History of economic thought, Wikipedia).

From now on there was a concrete example, how the Marxist theory could be implemented (respectively abused) in practice. Lenin’s centrally planned economy also marked the beginning of an endless competition between liberal and (partly) state-run economies. An obvious weakness of state-run economies was the inefficient allocation of the factors of production.

The Economic Calculation Problem

The Economic Calculation Problem is a criticism of using economic planning as a substitute for market-based allocation of the factors of production. It was first proposed by Ludwig von Mises in his 1920 article "Economic Calculation in the Socialist Commonwealth" and later expanded upon by Friedrich Hayek. In his first article, Mises describes the nature of the price system under capitalism and describes how individual subjective values are translated into the objective information necessary for rational allocation of resources in society. In market exchanges, prices reflect the supply and demand of resources, labor and products. In his first article, Mises focused his criticism on the inevitable deficiencies of the socialization of capital goods, but Mises later went on to elaborate on various different forms of socialism in his book, Socialism. Mises and Hayek argued that economic calculation is only possible by information provided through market prices, and that bureaucratic or technocratic methods result in an inefficient allocation of resources; see Austrian School (Economic Calculation Problem, Wikipedia).

Example:

As Paul mason writes (2016) in his book Postcapitalism there were around 24 million different products in the Soviet Union in 1980. The Moscow regime, which theoretically should have coordinated all economic activities in eleven time zones, only knew the prices and quantities of 200’000 products. And in the central plan, which set the long-term direction for the state-owned companies, just 2000 were recorded [Fuster].

The debate raged in the 1920s and 1930s, and that specific period of the debate has come to be known by economic historians as the Socialist Calculation Debate.

Market socialism

Market socialism was a response to the Economic Calculation Problem. It combines the public, cooperative, or social ownership of the means of production with the framework of a market economy (Market socialism, Wikipedia)

Market socialism combines Marxian economics with neoclassical economics (free markets) after dumping the labor theory of value (History of economic thought, Wikipedia).

Elements of market socialism were introduced in Hungary (where it was nicknamed goulash communism), Czechoslovakia and Yugoslavia (see Titoism) in the 1970s and 1980s. The contemporary Economy of Belarus has been described as a market socialist system. The Soviet Union attempted to introduce a market system in the 1980s with its perestroika reforms under Mikhail Gorbachev. The Chinese system is a mixture of market socialism and state capitalism, see Socialism with Chinese characteristics (Market Socialism, Wikipedia)

For information about the relation between political rights (democracy) and individual welfare see chapter 4.3.

3. Neoclassical Economics (since ca.1870)

Definition

Neoclassical economists defined economics as a science which is capable of studying all human rational actions. All humans can be modeled as agents who search for getting the maximal satisfaction from their actions. Firms can be modeled as rational entities striving to maximize their profit. The marginalist neoclassicals tried to develop general economic laws, imitating the rigorous methods used in physics (History of Economic Thought, Wikipedia).

Neoclassical economists assumed that people act independently on the basis of full and relevant information [Weintraub].

Origin

Neoclassical economics is conventionally dated from

1. William Stanley Jevons's Theory of Political Economy (1871)

2. Carl Menger's Principles of Economics (1871), and

3. Leon Walras's Elements of Pure Economics (1874 – 1877).

These three economists have been said to have promulgated the marginal utility revolution or Neoclassical Revolution.

1. Walras was more interested in the interaction of markets than in explaining the individual psyche through a hedonistic psychology. He suggested that economics is essentially a mathematical science.

2. Jevons saw his economics as an application and development of Jeremy Bentham's utilitarianism and never had a fully developed general equilibrium theory.

3. Menger emphasized disequilibrium and the discrete. Menger had a philosophical objection to the use of mathematics in economics, while the other two modeled their theories after 19th century mechanics.

(Neoclassical economics, Wikipedia)

The term neoclassical economics was invented by Thorstein Veblen, a heterodox institutional economist (and critic of capitalism), in the early 1900s to indicate that the marginal‐utility theory was, in virtue of utilitarianism and hedonism, essentially continuous with and so “scarcely distinguishable” from classical political economy (Neoclassical Economic Perspective, Milan Zafirovski)

The influence of science

There are heterodox theories (institutional economics, socioeconomics, evolutionary economics, etc.) as alternative meta-theoretical frameworks for constructing economic theories (…). But to the extent these schools reject the core building blocks of neoclassical economics; they are regarded by mainstream neoclassical economists as defenders of lost causes or as kooks, misguided critics, and antiscientific oddballs. The status of non-neoclassical economists in the economics departments in English-speaking universities is similar to that of flat-earthers in geography departments: it is safer to voice such opinions after one has tenure, if at all (…). How did such orthodoxy come to prevail? In brief, the success of neoclassical economics is connected to the "scientificization" or "mathematization" of economics in the twentieth century. Once neoclassical economics was associated with science, challenging the neoclassical approach was seen like challenging progress and modernity [Weintraub].

Today neoclassical economics dominates microeconomics and, together with Keynesian economics, forms the neoclassical synthesis which rules mainstream economics (Neoclassical Economics, Wikipedia)

Somewhere on the way to mainstream economics welfare economics took a separate path. Following the major steps in this development:

Definition

Major representatives of old welfare economics are Sidgwick (1838-1900), Marshall (1842-1929), and Pigou (1877-1959). They assumed that

- Utility is cardinal by observation or judgment; it can be measured in terms of money and is a measure for social welfare.

- All individuals have commensurable utility functions; utility is interpersonally comparable and summable.

- Additional consumption provides smaller and smaller increases in utility (diminishing marginal utility).

With these assumptions, it is possible to construct a social welfare function simply by summing all the individual utility functions.

(Welfare Economics, Wikipedia)

Marginal utility

The concept of diminishing marginal utility has a long history (see Marginalism, Wikipedia):

- Daniel Bernoulli (1700-1782) published a formalization of marginal utility in 1738 (Expected Utility Hypothesis, Wikipedia)

- Jevons, Menger and Walras promulgated the concept of marginal utility, but did not invent it.

- It was Gossen who found a convincing mathematical formulation and Pigou (not Bentham) who introduced it in a welfare function.

Hermann Heinrich Gossen (1810-1858) was a Prussian economist who is often regarded as the first to elaborate a general theory of marginal utility (Gossen, Wikipedia)

One of the major representatives of the Gossen-type of economics was the English economist Arthur Cecil Pigou. According to his theory the welfare of a society can be measured by the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the distribution of GDP [Kleinewefers, 40-42].

Welfare function according to Pigou

Let’s assume the society consists of two persons P1 and P2, who dispose of two goods G1 and G2. The welfare function according to Pigou would look as follows:

1. Social welfare (W) is the total of the two individual utilities (U): W = U1 + U2

2. The utility function is identical for both persons. It is assumed that the utility (usefulness) of the two goods is the same for both persons.

3. The utility function U = U (q1, q2) is of the Gossen type, i.e. the marginal utility of the quantities (q) of the two goods decreases with increasing consumption.

Under a given GNP the maximum social welfare can be attained, if the goods are equally distributed among the two persons [Kleinewefers, 41].

Distributive justice

As long as utility functions are assumed to be linear (as in Bentham’s welfare functions) it does not matter, if the welfare of the most or the least wealthy is increased. But if we assume a diminishing marginal utility of welfare (as in Pigou’s welfare functions) then it makes sense to increase the welfare of the least wealthy. Under the influence of Gossen’s laws a part of the welfare economists turned towards egalitarianism without being particularly compassionate. The normative force of the French revolution’s fraternité is not required to justify redistribution, as long as Gossen’s laws are seen as a kind of “natural” laws. Under the given premises redistribution is simply a consequence of the common goal to maximize the welfare of the community.

Pigous ideas are still effective in the actual discussions on

- Egalitarian utilitarianism (Pigouvian redistribution)

- Protection of the environment (Pigovian tax for pollution etc.)

Criticism

There are two main weaknesses in Pigou’s theory:

1. The theory assumes that the utility functions of all individuals are equal [Herbener, 80]. In reality, however, utilities are not independent. The marginal utility from a kilogram of coffee, for instance, depends on whether one owns an espresso machine or only a saucepan. Francis Edgeworth (1845-1926) dealt with this problem by proposing that total utility (of a consumer) is a function of the entire basket of goods (coffee and espresso machine, for example) faced by the consumer. More preferred bundles could be located above less-preferred ones. Bundles having the same value could be joined together to form an indifference curve. This analysis soon led to the ordinal revolution in utility theory, which eliminated all reference to total utility [Read].

2. The theory assumes that the society’s total income isn’t affected by the redistribution. If we take into account, however, that the society’s total income is negatively affected by an egalitarian policy (because the hard-working cannot earn more and the lazy don’t have to earn more) then the optimal redistribution is rather prioritarian than egalitarian.

Definition

The commensurability of utility functions was given up in new welfare economics [Clarenbach, chapt.2.6] [Herbener, 81]. Pareto (1848-1923) proved that utility is immeasurable from observations of behavior. Economists who accepted this proof (like Kaldor and Hicks) attempted to revise the theory of consumer behavior by excluding immeasurable concepts of utility. The analytical framework remained individualistic. All social phenomena (in particular market prices and the law of demand) had to be explained in terms of individual behavior.

Ordinal instead of cardinal utility is the major difference between old and new welfare economics [Kleinewefers, 42]. For a comparison see Cardinal Utility, Wikipedia.

When cardinal utility is used, the magnitude of utility differences is treated as an ethically or behaviorally significant quantity. On the other hand, ordinal utility captures only ranking and not strength of preferences (…). It would e.g. be possible to say that juice is preferred to tea or water, but no more. Normative economics has largely retreated from using cardinal utility functions as the basic objects of economic analysis, in favor of considering agent preferences over choice sets (Utility, Wikipedia).

Pareto

The first usage of ordinal utility is attributed to Vilfredo Pareto (1848-1923). Pareto rejected the idea that quantities of utility mattered. He observed that if we map preferences onto Edgeworth’s indifference curves (see end of chapter 3.2), we know everything necessary for economic analysis. To map these preferences, we obtain pairwise comparisons between possible consumption bundles. The agent will either be indifferent between each bundle, or else will prefer one to the other. By obtaining comparisons between all bundles, we can draw a complete map of an individual’s utility. To predict his or her choices under a given budget constraint, we then need only to determine which bundle(s) are on the highest achievable indifference curve. Conversely, we can also assume, from the individual’s choice, that because a bundle is chosen, it must be on that highest indifference curve (the principle of revealed preference). Observe that Pareto’s procedure makes no reference to any cardinal utility measure [Read]. Only relative utility is measured, not absolute utility. Relative utility is sufficient to predict economic decisions.

Pareto demolished the alliance of economics and utilitarian philosophy (which calls for the greatest good for the greatest number). He replaced the “good” with the notion of Pareto-efficiency (Pareto, Wikipedia).

As a consequence, there is no variable like “welfare” which could be maximized and distributed. With the focus on efficiency, distributive justice was cancelled from the economist’s agenda.

Allocative efficiency

From now on economics concentrated on the search for allocative efficiency under the conditions of a given initial allocation and limited resources.

Given a set of alternative allocations of goods or outcomes for a set of individuals, a change from one allocation to another that can make at least one individual better off without making any other individual worse off is called a Pareto-improvement. An allocation is defined as Pareto-efficient when no further Pareto-improvements can be made (Pareto efficiency, Wikipedia).

Example: Suppose we have an economy with only two goods (apples and oranges) and two people (Person A and Person B). In the initial state, Person A has all the apples, and Person B has all the oranges. Now they start exchanging apples and oranges:

- If Person A gives an apple to Person B in exchange for an orange, then it’s a Pareto improvement if Person A likes getting an orange more than giving away an apple and if Person B agrees with the deal.

- However, once we reach a state where Person A and Person B both have apples and oranges, and at least one person doesn’t want to continue exchanging, we’ve reached Pareto efficiency. Any further trades would make one person worse off.

This concept is independent of the prices of the goods and services. It’s about the distribution of resources based on individuals’ preferences, disregarding the market prices of these resources. For more information see “Examples and exercises on Pareto efficiency”, M.Osborne, Toronto Economics.

Fundamental theorems

Two fundamental theorems of welfare economics are the following:

1. A perfectly competitive general equilibrium is Pareto-efficient [Arrow, 97]

- The theorem captures the logic of Adam Smith’s invisible hand (Welfare Economics, Wikipedia)

- Corollary: Free trade is Pareto-efficient among countries.

2. Any Pareto-efficient allocation can be attained by a competitive general equilibrium.

For a more detailed description see General Equilibrium Theory.

Why do free markets tend to be Pareto-efficient? The Pareto principle, or “80/20 rule” posits that for many outcomes, roughly 80% of consequences come from 20% of causes. For instance, 80% of a service company’s turnover may come from 20% of its services. If the company is aware of this distribution, it can improve its efficiency by focusing on the most in-demand 20%. Society can be seen as a large entity producing a variety of products and services. Pareto, like Adam Smith in the past, argued that only free markets allow for the identification of which products and services are most desired by consumers, and only a competitive environment guarantees that these products and services are created efficiently. Kenneth Arrow was the first economist who found a theoretical proof for the conjecture that free markets tend towards Pareto-efficiency.

Criticism

Pareto efficiency was criticized for two reasons:

1. It does not require a "just" or equitable distribution of wealth. A simple example is dividing a pie into pieces to distribute among three people. The most equitable distribution is each person getting one third. However, the solution of two people getting half a pie and the third person getting none is also Pareto-efficient despite not being equitable, because the only way for the person with no piece to get a piece is for one or both of the other two to get less, which is not a Pareto-improvement (Pareto efficiency, Wikipedia)

2. Varying initial allocations lead to varying solutions, and there is no criterion to compare these solutions. It is not even possible to compare Pareto-efficiency for a specific initial allocation with the non-efficiency of a different initial allocation. The only normative goal is to realize perfect competition in a perfect market to reach pareto-efficiency [Kleinewefers, 43-44]. Obviously, Pareto-efficiency cannot be applied to practical politics because political decisions normally produce winners and losers. Consequently, economics developed new criteria which could be applied to cases with winners and losers.

Using Kaldor-Hicks-efficiency, an outcome is more efficient if those that are made better off could in theory compensate those that are made worse off, so that a Pareto-improving outcome results. For example, a voluntary exchange that creates pollution would be a Kaldor-Hicks-improvement if the buyers and sellers are still willing to carry out the transaction even if they have to fully compensate the victims of the pollution (Kaldor-Hicks efficiency, Wikipedia). For an example of such compensation see Pareto-efficiency by T.Pettinger.

Using the new efficiency criteria, it was possible to compare a new situation with the status quo, but it was not possible to compare several alternatives and find the best one. The need to compare and rank a larger number of alternatives led to the development of new social welfare functions.

Distributive justice

Bentham and Pigou already defined social welfare functions (chapter 2.2 and 3.2), but these functions were cardinal and restricted to the consumption of goods and services. Pareto’s social welfare function, on the other hand, was ordinal, but focused on efficiency.

Furthermore, it turned out that it is not possible to evaluate a change which makes some persons better-off and some worse-off without making some implicit value judgment about the deservingness of an individual or a group. Recognizing the inevitability of value judgment, Abram Bergson suggested that the only way to solve this problem is to formulate a set of explicit value judgments about the distribution of income [Dwivedi].

In a 1938 article Bergson introduced a new type of social welfare function. The object was "to state in precise form the value judgments required for the derivation of the conditions of maximum economic welfare" set out by earlier writers, including Pigou, Pareto and others (Social welfare function, Wikipedia)

The term precise form does not mean that value judgments were fixed values. Since the goal was to formulate general economic laws and formulas (see chapter 3.1) value judgments were treated as variables.

According to Bergson a social welfare function should include all arguments which influence the members of the society in a positive or negative way.

Pareto-efficiency could characterize one dimension of a particular social welfare function, distribution of commodities among individuals another dimension. Paul Samuelson stressed the flexibility of the social welfare function to characterize any one ethical belief, Pareto-bound or not, consistent with a complete and transitive ranking (an ethically "better", "worse", or "indifferent" ranking) of all social alternatives (Social welfare function, Wikipedia).

Like Pareto’s approach the Bergson-Samuelson social welfare functions are also concerned with the distribution of resources based on individuals’ preferences, disregarding the market prices of these resources.

Definition

Social choice theory is the study of collective decision processes and procedures (Social Choice Theory, Stanford)

In a narrower sense social choice theory strives to aggregate individual preferences into a combined social welfare function.

- Individual preferences can be modeled in terms of a utility function.

- The ability to sum utility functions of different individuals depends on the utility functions being comparable to each other (Social Choice Theory, Wikipedia)

Pioneered in the 18th century by Nicolas de Condorcet and Jean-Charles de Borda and in the 19th century by Charles Dodgson social choice theory took off in the 20th century with the works of Kenneth Arrow, Amartya Sen, and Duncan Black (Social Choice Theory, Stanford).

Arrows impossibility theorem

In his dissertation Social Choice and Individual Values (1951) Arrow proved that there is no democratic decision process which aggregates individual preferences into an unambiguous result [Kleinewefers, 48-52].

Because of welfare economics' close ties to social choice theory, Arrow's impossibility theorem (1951) is sometimes listed as a third fundamental theorem of welfare economics (Welfare economics, Wikipedia).

The difficulties in the aggregation are caused by the assumption (of new welfare economics) that individual preferences are not comparable and therefore not cardinally measurable.

In the following there was a controversy between welfare economists and social choice theorists as a consequence of Arrow’s impossibility theorem. The 1970’s witnessed a new version of the theorem that was meant to establish that the Bergson-Samuelson social welfare functions “make interpersonal comparisons of utility”. Against this, Samuelson reasserted the existence of well-behaved “ordinalist” social welfare functions and generally denied the relevance of Arrovian impossibilities to welfare economics [Fleurbaey].

Neither Bergson nor Samuelson, however, precisely defined their social welfare functions. It remained unclear

- how the arguments of these functions should be measured, respectively (if there is no cardinal measure)

- how ordinal utilities should be aggregated

[Kleinewefers, 45-48].

There are some ways out of the trap by reducing complexity:

1. In John Harsanyi’s (1920-2000) theory individual preferences are subjected to the judgment of an impartial and empathic observer, who makes a distinction between “representative” preferences and individual extravagances. The former – which he calls (empathically) extended preferences – are made comparable by a normative act. They are considered in the aggregation, whereas the latter are neglected [Adler]. Since this approach reintroduces cardinality on the individual level, Harsanyi may be viewed as the last exponent of old welfare economics (Economics and Economic Justice, Stanford). John Broome elaborated and extended Harsanyi's theory [Broome].

2. Amartya Sen (1933- ) replaces the individual preferences by capabilities (freedoms, opportunities). Capabilities are defined on the level of constitutions and are made comparable by a normative act. Since cardinality only exists on the constitutional level, this approach is clearly different from old welfare economics.

3. John Rawls (1921-2002) replaces the individual preferences by goods on the constitutional level, as well as Sen. But he arranges his most important goods (liberty rights, equality of opportunity and economic welfare) on a priority scale, instead of making them comparable.

Following Harsanyi’s and Sen’s approach in more detail (for details on Rawls concept see Negative Utilitarianism and Justice):

Harsanyi’s utilitarianism

In accordance with the principles of neoclassical economics (chapter 3.1) Harsanyi’s impartial observer acts rational and attempts to maximize utility under given side constraints. The theory assumes that – after every decision influencing or changing society – the observer can find him-/herself with equal probability in every possible position in the changed society (Gleichwahrscheinlichkeitsmodell).

For the observer this is a risky situation in which the standard decision criterion is expected utility. The computation of expected utility yields an arithmetic mean of the utilities that the observer would have, if he became anyone in the population (Economics and Economic Justice, Stanford).

The concept of the utility function – which builds on the expected utility theorem – is sufficiently flexible in order to address all relevant problems of individual rationality. It allows taking account of social interdependencies, external effects, (economic) public goods and even political goods (like human rights). In other words: the term utility is associated with general welfare instead of economic welfare. The problem with utility functions is not a theoretical one, it is a practical one. There is no complete utility function for an individual [Kleinewefers, 277] and no estimation for the cardinal values.

Sen’s capability approach

Traditional welfare economics (Bentham, Pigou) tends to identify a person's well-being with the person's command over (economic) goods and services. Sen, as well as Harsanyi, associates the term utility with general welfare instead of economic welfare. He valuates social situations according to capabilities (freedoms, opportunities) which are offered to individuals. The usage of these capabilities is then a concern of the individuals and not of society.

Similar to Harsanyi’s attempt to find “representative” preferences, Sen attempts to find “representative” capabilities by subjecting them to the judgment of an impartial and empathic observer. The capability approach runs across the aggregation problem on a constitutional level. Economic goods and political goods (like human rights) are not measured according to the same cardinal scale and cannot be accumulated into a single value called “social welfare” [Kleinewefers, 53-54]. Sen and other social choice theorists make their most important goods comparable by a normative act and aggregate them into an index (chapter 4.3).

Distributive justice

Harsanyi’s and Rawls’ concept both convert normative statements about solidarity into normative statements about risk. However, Harsanyi rejects Rawls risk-averse strategy, claiming that it is irrational to make behaviour dependent on some highly unlikely unfavourable contingency regardless of its low probability [Harsanyi, 1975]. Progressive tax can be seen as a compromise between Harsanyi’s and Rawls’ positions.

Sen defends Rawls’ justice as fairness [Rawls, 1958] but not its derivation from the original position (The Idea of Justice, Wikipedia).

With the neoclassical researchers (see chapter 3.1) economics started to split up into microeconomics and macroeconomics. Whereas Jevons concentrated on microeconomics, Walras and Menger worked on equilibrium theory which became the cornerstone of macroeconomics. In the 20th century micro- and macroeconomics continued to develop in parallel with social choice theory:

▪ Social choice theory had a normative ambition and delt with general welfare.

▪ Micro- and macroeconomics were more descriptive (with the exception of Keynesianism) and restricted to economic welfare.

Microeconomics

- Neoclassical economists were above all involved in the development of microeconomics, a science they have founded, even if the idea that all human pursued their self-interest was already mentioned in Smith, Ricardo and Mill’s works (History of Economic Thought, Wikipedia).

- Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of limited resources. One goal of microeconomics is to analyze the market mechanisms that establish relative prices among goods and services (supply and demand). Microeconomics also analyzes market failure, where markets fail to produce efficient results, and describes the theoretical conditions needed for perfect competition (Microeconomics, Wikipedia)

Macroeconomics

- Macroeconomics deals with the performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole.

- Léon Walras first formalized the idea of a one-period economic equilibrium, but it was French economist Antoine Augustin Cournot and English political economist Alfred Marshall who developed tractable models to analyze an economic system (Partial Equilibrium, Wikipedia)

- Early macroeconomic researchers explained broad aggregates and their interactions “top down,” that is, using a simplified form of general-equilibrium theory.

- Macroeconomists study aggregated indicators such as GDP, unemployment rates, and price indices. They develop models that explain the relationship between such factors as national income, output, consumption, unemployment, inflation, savings, investment, international trade and international finance (Macroeconomics, Wikipedia)

Relation to welfare economics

Welfare economics used microeconomic knowledge to develop social welfare functions. As mentioned in the previous chapter the major problem was to measure the arguments of these functions. Whereas social choice theorists developed various ways to circumvent the problem (chapter 3.4), new welfare economists struggled in vain for several decades to show how ordinal ranks relate to cardinal numbers. Had they not been wedded to their mathematical formulations, perhaps they could have accepted the solution given by the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises. From his development of the concept of ordinal marginal utility in 1912 Mises went on to explain how ordinal utility can be the basis for socially-meaningful cardinal comparisons of value. Money is a common denominator in which ordinal preferences can be expressed. Exchanges of private property for and against money result in cardinal numbers, namely money prices, for all goods and factors traded on the market [Herbener, 81].

Marginal utility is a consequence of rational behavior: Instead of the price of a good or service reflecting the production cost (as in classical economics), the price reflects the marginal usefulness of the last purchase. This means that in equilibrium, people's preferences determine prices, including, indirectly the price of labor (History of economic thought, Wikipedia).

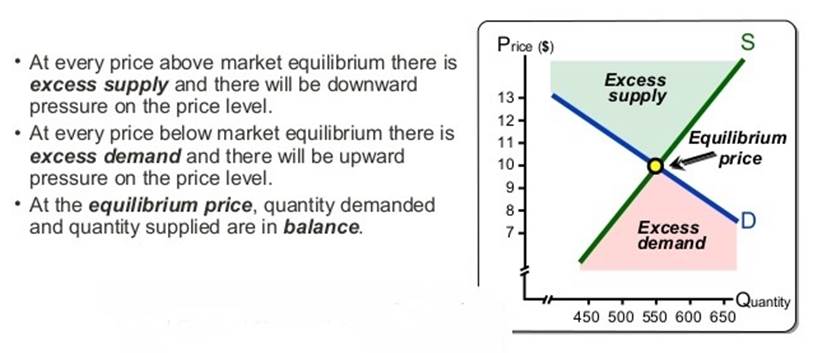

Supply and demand are the driving forces behind the production and pricing of goods and services:

Picture from the internet (author unknown)

Using the concept of market prices, it was possible to develop a cardinal consumer theory, which later served as a basis to solve the aggregation problem. There were, however, two challenges in Mises’ approach:

1. Welfare is driven by the market and cannot be (fairly) planned and maximized (or optimized) by means of mathematical methods. The ambition of old and new welfare economics had to be given up.

2. The forces of the market don’t regulate everything for the best. An illustrative example was the so-called Great Depression.

The Great Depression (1930s)

Until the Great Depression economists implicitly assumed that either markets were in equilibrium – such that prices would adjust to equalize supply and demand – or that in the event of a transient shock, such as a financial crisis or a famine, markets would quickly return to equilibrium. In other words, economists believed that the study of individual markets would adequately explain the behavior of what we now call aggregate variables, such as unemployment and output.

The severe and prolonged global collapse in economic activity that occurred during the Great Depression changed that. It was not that economists were unaware that aggregate variables could be unstable. They studied business cycles—as economies regularly changed from a condition of rising output and employment to reduced or falling growth and rising unemployment, frequently punctuated by severe changes or economic crises. Economists also studied money and its role in the economy. But the economics of the time could not explain the Great Depression [Rodrigo].

Keynes’ critique

Some of the notions of modern macroeconomics are rooted in the work of scholars such as Irving Fisher and Knut Wicksell in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but the major change of the discipline began with Keynes’s masterpiece, The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money, in 1936. Its main concern is the instability of aggregate variables. Keynes introduced the simultaneous consideration of equilibrium in three interrelated sets of markets—for goods, labor, and finance. He also introduced “disequilibrium economics,” which is the explicit study of departures from general equilibrium [Rodrigo]

Keynesian economists argue that private sector decisions sometimes lead to inefficient macroeconomic outcomes which require active policy responses by the public sector, in particular, monetary policy actions by the central bank and fiscal policy actions by the government, in order to stabilize output over the business cycle. Keynesian economics advocates a mixed economy – predominantly private sector, but with a role for government intervention during recessions (Keynesian Economics, Wikipedia)

Picture from the internet

Keynes had trained at Cambridge University as a mathematician (…). When he turned his attention to economics, he was shocked by the way mathematical economists abused mathematics (…) and he made no secret of his professional contempt for their empty pretentiousness. But these economists were soon to have their revenge. Led by Paul Samuelson in the US and John Hicks in the UK, they set about mathematicising Keynes’ theory [Fullbrook].

Definition

Neoclassical synthesis is a postwar academic movement in economics that attempts to absorb the macroeconomic thought of John Maynard Keynes into the thought of neoclassical economics. Mainstream economics is largely dominated by the resulting synthesis, being

- Keynesian in macroeconomics and

- neoclassical in microeconomics.

The theory was mainly developed by John Hicks, and popularized by the mathematical economist Paul Samuelson (Neoclassical Synthesis, Wikipedia)

Criticism of Keynesian macroeconomics

As inflation increased in the late 1960s, the empirical success and, in turn, the theoretical foundations of the synthesis were more and more widely questioned. The more serious blow was, however, the stagflation of the mid-1970s in response to the increases in the price of oil: it was clear that policy was not able to maintain steady growth and low inflation. In a clarion call against the neoclassical synthesis, Lucas and Sargent (1978) judged its predictions to have been an ‘econometric failure on a grand scale’ [Blanchard, 4].

- In the 1960s Milton Friedman’s published his monetarist critique of Keynesian macroeconomics.

- In the 1970’s Robert E. Lucas, Jr. refuted the idea that government intervention can or should stabilize the economy (History of Economic Thought, Wikipedia).

The Lucas critique, named for Robert Lucas’s work on macroeconomic policymaking, says that it is naïve to try to predict the effects of a change in economic policy entirely on the basis of relationships observed in historical data, especially highly aggregated historical data (Lucas critique, Wikipedia).

New Neoclassical Synthesis / New Keynesianism

In the wake of the Lucas critique, much of modern macroeconomic theory has been built upon microfoundations, in particular the so-called New Neoclassical Synthesis (1990s) which is used by the Federal Reserve and many other central banks (Microeconomics, Wikipedia).

- The rational behavior of individuals, households or firms is the basis for simulating individual markets

- Individual markets are integrated into a model of aggregate economy.

[Woodford, 4].

The school, which strives to explain short-run fluctuations in the economy, is also known as New Keynesianism.

Both, the Bush and the Obama Administration adopted Keynesian politics in response to the financial crisis in 2008 [Crain, 93].

The new synthesis did not expect full employment to occur under laissez-faire; it believed, however, that, by proper use of monetary and fiscal policy, the old classical truths would come back into relevance [Blanchard, 1]:

- The “old classical truths” say that free markets are the best means of inducing rapid and successful development (Development Economics, Wikipedia).

- The new synthesis believes that the “proper use of monetary and fiscal policy” is able to avoid crises. Financial and economic crises are closely interconnected. A financial crisis can lead to an economic crisis (stagflation, recession, depression) and vice-versa. Traditionally the research focused on macroeconomic phenomena like the change in interest rates, business cycles and debt ratios. The new research, in contrast, includes the microstructure of financial markets and institutions [Straumann] [Eichengreen].

Relation to welfare economics

Welfare economics does not represent mainstream economics (…). Mainstream economic policies in Western countries (and in a growing number of non-Western countries) focus on how to improve the working of free markets. These policies were not dominant during the 1950s-70s when Keynesian policies prevailed. And those policies prevailed too long, leading to the combination of inflation and stagnation called stagflation. Neoclassical free market-oriented policies became the mainstream in the 1980s. The collapse of the centrally planned Eastern European economics systems reinforced the dominance of present mainstream economics [OECD, 268].

▪ The important field of welfare economics has never fully recovered from the demise of cardinal utility [Selikoff, 43].

Welfare cannot be maximized, and distributive justice cannot be reintroduced to the economist’s agenda, as long as there is no consent on the parameter values within the social welfare functions. Only a social system of unanimous consent (on these parameters) can generate the greatest benefit for society.

▪ The neoclassical synthesis claims that the free market – which creates this consent – is the economic condition for generating the greatest benefit [Herbener, 85]. This claim stands clearly in the tradition of Adam Smith’s invisible hand and Pareto’s theorems.

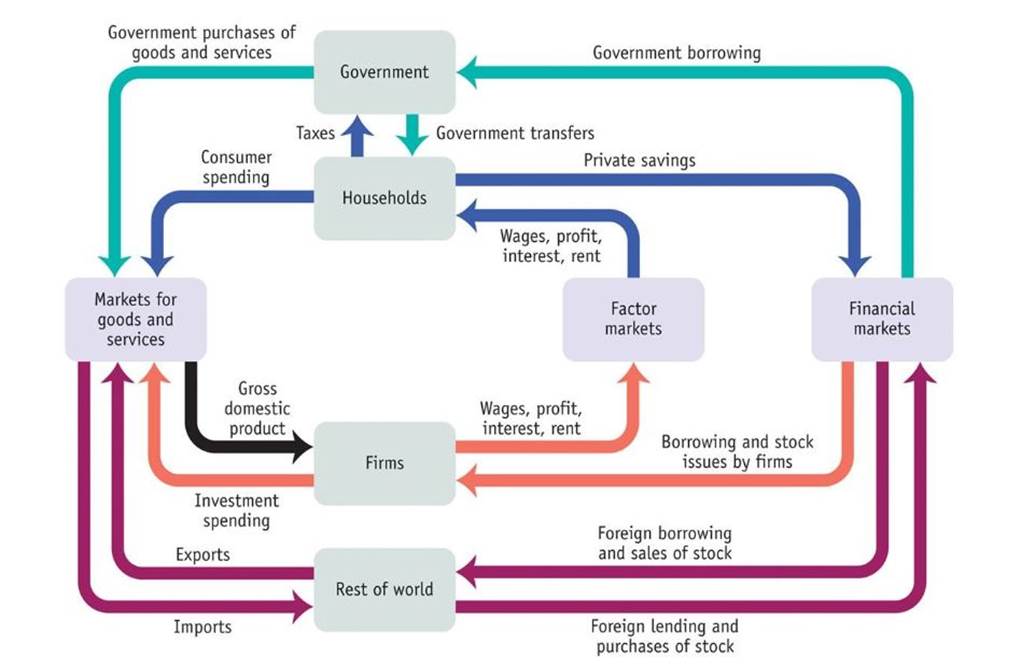

The model of mainstream economics below makes intuitively clear, that it is impossible to plan total welfare without simulating markets. The classical utilitarian goal to maximize welfare is replaced by the simulation and comparison of different monetary and fiscal policies.

Picture from the internet (Author unknown)

Furthermore mainstream economics is restricted to the investigation of economic welfare, and happiness (well-being, life satisfaction) cannot be reduced to economic welfare [Nishizawa] [Suzumura]. For many determinants of happiness there is no market and no price (fortunately).

Given this diagnosis: What happened to the classical utilitarian goal to maximize happiness? The most promising strategies are probably those, which have given up the idea to derive happiness exclusively from economic welfare. Prominent representatives of these new strategies are

- The Capability Approach (chapter 4.3)

- Happiness Economics (chapter 5)

4. Modern Development Economics (since ca.1950)

Development economics is a branch of economics which deals with economic aspects of the development process in low-income countries. Its focus is not only on methods of promoting economic development, economic growth and structural change but also on improving the potential for the mass of the population, for example, through health, education and workplace conditions. Unlike in many other fields of economics, approaches in development economics may incorporate social and political factors to devise particular plans (Development Economics, Wikipedia).

The origins of modern development economics are often traced to the need for, and likely problems with the industrialization of Eastern Europe in the aftermath of World War II (Development Economics, Wikipedia).

In the context of development economics neoclassical theory is a consequence of Robert Lucas‘critique of government intervention in the 1970s (chapter 3.6).

Neoclassical theory gained prominence with the rise of several conservative governments in the developed world during the 1980s. These theories represent a radical shift away from international dependence theories. Neoclassical theories argue that governments should not intervene in the economy and that an unobstructed free market is the best means of inducing rapid and successful development. Competitive free markets unrestrained by excessive government regulation are seen as being able to naturally ensure that the allocation of resources occurs with the greatest efficiency possible.

It is important to note that there are several different approaches within the realm of neoclassical theory, each with subtle, but important, differences in their views regarding the extent to which the market should be left unregulated. These different takes on neoclassical theory are the free market approach, public-choice theory, and the market-friendly approach.

- Of the three, both the free-market approach and public-choice theory contend that the market should be totally free, meaning that any intervention by the government is necessarily bad. Public-choice theory is arguably the more radical of the two with its view, closely associated with libertarianism that governments themselves are rarely good and therefore should be as minimal as possible.

- The market-friendly approach, unlike the other two, is a more recent development and is often associated with the World Bank. This approach still advocates free markets but recognizes that there are many imperfections in the markets of many developing nations and thus argues that some government intervention is an effective means of fixing such imperfections.

(Development Economics, Wikipedia).

Above theories do not question the (classical utilitarian) assumption that economic growth improves social welfare. The criteria for ranking nations are still

- Income for the welfare of the individual

- GDP (calculated by the income approach) for the welfare of society.

The measurement of the GDP, however, has its pitfalls [Coyle].

|

The Gross Domestic Product measures everything except that which makes life worthwhile.

|

A fundamental critic of orthodox welfare economics says that general welfare (happiness, well-being, life satisfaction) cannot be reduced to economic indicators.

Example:

In 1974 seven West African nations got together, contacted donors and set out to create the Onchocerciasis Control Program, overseen by the World Health Organization. The program was a huge success, in that it prevented hundreds of thousands of people from going blind, but there was a problem: the economists involved couldn’t show that the venture was worth it. A cost-benefit analysis was “inconclusive”: the people who were being helped were so poor that the benefit of saving their eyesight didn’t have much monetary impact (…). In other words, the very thing that made the project so admirable – that is was improving the lives of the poorest people in the world – also made it, from an economic point of view, not really worth doing [Lanchester, 62].

Social indicators like material security, political liberty, social justice, legal security and health care are essential for welfare [Kleinewefers, 56-58]. All these indicators question the List of Countries by GDP per Capita. The most prominent development economist promoting social indicators is the 1998 Nobel laureate, Amartya Sen. His name is associated with the term capability approach:

Indian economist Amartya Sen expressed considerable skepticism about the validity of neoclassical assumptions, and was highly critical of rational expectations theory, devoting his work to Development Economics and human rights (History of Economic Thought, Wikipedia)

Definition

The Capability Approach emphasizes functional capabilities (such as the ability to live to old age, engage in economic transactions, or participate in political activities); these are construed in terms of the substantive freedoms people have reason to value (…). Someone could be deprived of such capabilities in many ways, e.g. by ignorance, government oppression, lack of financial resources, or false consciousness (Capability Approach, Wikipedia)

Economic and social progress – as understood by the capability approach – can be measured by indices.

Examples:

- The Human Development Index (HDI) published by the United Nations Development Program combines the standard of living (as measured by the natural logarithm of gross domestic product per capita) with life expectancy, adult literacy rate and the gross enrollment ratio.

- The Social Progress Index was developed based on extensive discussions with stakeholders around the world about what has been missed when policymakers focus on GDP to the exclusion of social performance.

- A list which combines the indicators political liberty, legal security and social justice is the Democracy Ranking.

- Traditional economic indicators (like GDP) don’t account for the exploitation of natural resources and therefore allow consumption at the cost of future generations. A recently proposed alternative for GDP is the Genuine Progress Indicator (GPI).

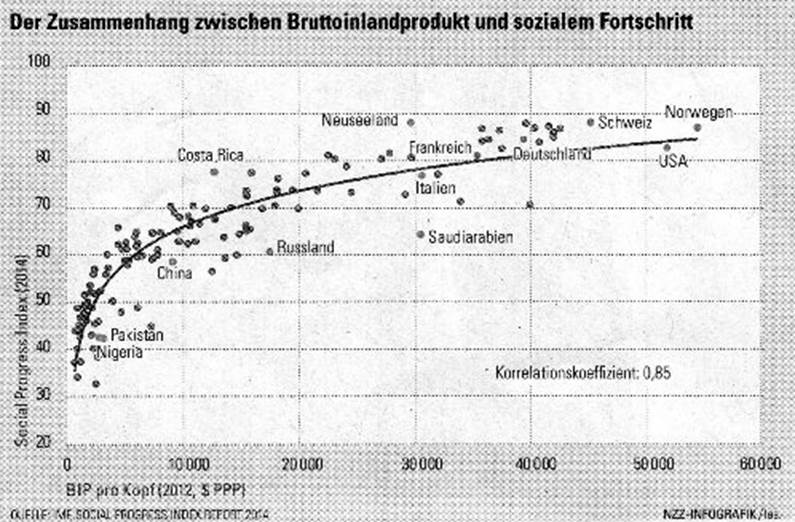

Correlation with the GDP

A recent (2014) IMF project investigated the correlation between the Social Progress Index and the GDP. One of the interesting results was the following:

- Costa Rica reaches almost the same level of social progress as the United States, although the GDP per capita is only a quarter.

- Costa Rica has a substantially higher social progress than Saudi Arabia, although the GDP per capita is less than half.

This seems to confirm Kennedy’s claim (chapter 4.2) that there is no correlation between the GDP and life satisfaction. In countries with a lower GDP per capita than Costa Rica, however, things look different:

The overall picture suggests that social progress improves roughly with the logarithm of the GDP. A logarithmic function is reminiscent of Gossen’s observation of the diminishing marginal utility of economic welfare and corresponds to the above mentioned Human Development Index. The correlation between economic progress and democracy is of special interest:

- As long as physical survival remains uncertain, the desire for physical and economic security tends to take higher priority than democracy.

- When basic needs are fulfilled, however, there is a growing emphasis on self-expression [World Values Survey]. Life satisfaction then correlates stronger with the democracy-index than with any other of the current indices [Schwarz].

Development aid

Can social progress be accelerated by development aid?

- The quality of development aid is criticized insofar, as donors may give with one hand, through large amounts of development aid, yet take away with the other, through strict trade or migration policies, or by getting a foothold for foreign corporations. The Commitment to Development Index measures the overall policies of donors and evaluates the quality of their development aid, instead of just comparing the quantity of official development assistance given.

- The effectiveness of development aid is criticized as well. Many econometric studies in recent years have supported the view that development aid has no effect on the speed with which countries develop. Negative side effects of aid can include an unbalanced appreciation of the recipient's currency (known as Dutch Disease), increasing corruption, and adverse political effects such as postponements of necessary economic and democratic reforms.

2015 Nobel Prize winner Angus Deaton suggests in his recent book The Great Escape [Deaton] that development aid does not work, and that it can increase corruption and keep bad leaders in power.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology started a rigorous study [Banerjee 2003, 2011] of the relatively few independent evaluations of aid program successes and failures (Development Aid, Wikipedia).

5. Happiness Economics (since ca.2005)

Origin

Thomas Jefferson put the “pursuit of happiness” on the same level as life and liberty in the constitution of the United States. Many prominent economists and philosophers throughout history – including Aristotle – incorporated happiness into their work (Happiness Economics, Wikipedia).

In this context the term happiness is a synonym for well-being and life satisfaction.

Happiness economics – in today’s understanding – may have started with the introduction of the Gross National Happiness (GNH) in Bhutan. At this time, however, there was no exact quantitative definition of GNH. The first GNH Index – also known as Gross National Well-being – was introduced in 2005.

Definition

Happiness economics is the study of a country's well-being by combining economists' and psychologists' techniques. The goal is to determine from what source people derive their well-being (Happiness Economics, Wikipedia)

Happiness economics examines the determinants of life satisfaction by means of surveys, thereby connecting micro- and macroeconomics. The result is an average or “representative” utility function [Kleinewefers, 278] with subjective life satisfaction on one side and the statistical determinants on the other side. Determinants are those social indicators which are relevant for the life satisfaction of the majority [Kleinewefers, 58].

Happiness economists hope to change the way governments view well-being and allocate resources in the light of empirical data. They challenge conventional economic theory on two accounts:

- They question the rational utility maximization principle of the homo oeconomicus (chapter 5.2)

- They question the definition of social indicators by bureaucratic elites and the use of untested assumptions about the determinants of happiness (chapter 5.3)

Obviously, after a long detour, welfare economics returned to its classical target, which was the greatest happiness for the greatest number of people [Hirata, 21].

5.2 Criticism of Neoclassical Economics

Following a summary of the empirical findings:

- On the biological level people have their preferences, but on the cultural level people rather make than have their preferences.

- Behavior systematically deviates from happiness maximization, both intentionally and erroneously. People sometimes account for moral considerations at the cost of subjective well-being; and sometimes they take decisions mindlessly. Consequently, the assumption that everyone is the best judge of what will make him/her happy is by no means unchallenged. This conclusion should not come as a surprise. After all, economic decision theory is built upon psychological ad hoc assumptions which qualified primarily on formal, rather than substantive grounds. They were convenient because they warrant internal consistency and analytical versatility, making them amenable to quantitative analyses. Similarly in the context of consumption, welfare economics relies on an uncritical generalization of the casual observation of individual consumption decisions and their motivations.

The Homo Oeconomicus is an inadequate description of human behavior. Neoclassical economics will have to be reassessed in the light of empirical findings. All the important theories in this field (in particular the general equilibrium theory) depend on the relation between behavior and welfare through the intermediary of preferences [Hirata, 26]. Adherents of happiness economics replace individual welfare functions by surveys on subjective life satisfaction.

|

It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong.

|

For a detailed critique of neoclassical economics see The Flawed Assumptions of Neoclassical Economic Idealization [ANU].

5.3 Subjective versus Objective Data

Subjective indices

Social indicators (chapter 4.3) as well as the GDP are based on objective data. The basic new idea of happiness economics consists in relating objective data to subjective happiness. Social indicators are often defined by bureaucratic elites and rely on untested assumptions [Kleinewefers, 277]. Indicators, once they are established, develop a normative force and influence politics. It is therefore necessary to check the relation between objective indicators and subjective well-being by means of surveys.

Examples:

1. The Satisfaction with Life Index is an attempt to show the average self-reported happiness (subjective life satisfaction) in different nations. This is an example of a recent trend to use direct measures of happiness, such as surveys asking people how happy they are, as an alternative to traditional measures of policy success to GDP or GNP (…) (Happiness Economics, Wikipedia)

2. The World Happiness Report is the result of a UN General Assembly resolution, inviting member countries to measure the happiness of their people and to use this to help guide their public policies.

Combined indices

1. Happy Life Years, a concept brought by Dutch sociologist Ruut Veenhoven, combines self-reported happiness with life expectancy (…). Veenhoven is one of the chief critics of (…) the Human Development Index published by the United Nations Development Programme (…). Happy Life Years may be a better indicator of happiness as it relies on subjective measures of happiness (Happy Life Years, Wikipedia)

2. The Happy Planet Index combines self-reported happiness with life expectancy and ecological footprint. The HPI is based on general utilitarian principles — that most people want to live long and fulfilling lives, and the country which is doing the best is the one that allows its citizens to do so, whilst avoiding infringing on the opportunity of future people and people in other countries to do the same (Happy Planet Index, Wikipedia).

3. An interesting experiment is taking place in Bhutan, the only country that replaced the GDP by the Gross National Happiness (GNH). The nine domains of GNH are psychological well-being, health, time use, education, cultural diversity and resilience, good governance, community vitality, ecological diversity, and resilience, and living standards. Each domain is composed of subjective (survey-based) and objective indicators (Gross National Happiness, Wikipedia).

4. The Better Life Index considers 11 dimensions of well-being, partly based on self-reported data and partly based on objective data.

Explanations for the Easterlin Paradox

For countries with income sufficient to meet basic needs, the following explanations were found:

1. People’s happiness over time closely tracks changes in inequality. The overall wealth, measured by GDP, tends to have little effect. In other words: We measure our success relatively. Our perceptions of how our income relates to other people’s matters as much, if not more, than the actual amount we earn.

2. A second explanation comes from studies of social capital. Social capital is often measured by getting people to rate how much they trust the people around them. If an increase in GDP doesn’t increase people’s happiness, then it is often because of a decrease in social capital.

3. A third explanation has to do with the quality of a country’s institutions and the ways that they look after those who are in need – through healthcare, unemployment benefits and pensions. Without an improvement of the country’s institutions, an increase in GDP doesn’t necessarily increase people’s happiness.

[Robson].

Criticism

Happiness economics does not account for the suffering people who cannot participate in surveys. Furthermore, in the established indices, the worst cases of suffering disappear in the average, suggesting that they can easily be compensated by the majority’s happiness. Empirical research has shown, however, that such compensation is far from evident; see Is There a Predominance of Suffering?. Assigning more weight to suffering could

- strengthen the awareness that the suffering minority pays (in a statistical sense) the price for the happiness of the majority; see Negative Utilitarianism and Justice

- reveal cases, where the average welfare improves, and the situation of the suffering minority worsens

- challenge current population policies by the claim that total welfare is negative; see Antinatalism and the Minimization of Suffering

There are good reasons to amend or replace Happiness Economics by a Suffering-focused Economics.

6. On the Philosophy of Economics

Definition

Positive economics (as opposed to normative economics) is the branch of economics that concerns the description and explanation of economic phenomena. Positive economics concerns the analysis of economic behavior and avoids value judgements. For example, a positive economic theory might describe how money supply growth affects inflation, but it does not provide any instruction on what policy ought to be followed. Positive economics is sometimes defined as the economics of "what is", whereas normative economics discusses "what ought to be" (Positive Economics, Wikipedia)

Today’s mainstream economics is positive economics (value-free) and strives to simulate markets as realistically as possible.

Historically positive economics has two sources:

1. Critical rationalism

2. Econometrics

Critical rationalism

- The critics of old welfare economics was connected with the dispute on values in economics. Classical economics did not clearly distinguish between normative and descriptive statements. In the context of Popper’s critical rationalism (1934 The Logic of Scientific Discovery) economics attempted to become a science, i.e. a theory that is based on logic and empirical data.

- The marginalist neoclassicals tried to develop general economic laws, imitating the rigorous methods used in physics (History of Economic Thought, Wikipedia).

- New welfare economics abstains from value judgments. The values within Bergson’s social welfare function, for example, are treated as variables. But by investigating the conditions for efficient welfare (Pareto) or maximum welfare (Bergson), new welfare economics clearly aimed at delivering input for normative economics.

Econometrics

Besides Popper’s critical rationalism it was the emergence of econometrics in the 1930s, which encouraged positive economics. Simulation models were supposed to support normative economics

- by estimating the outcomes of competing economic policies and

- by predicting economic crises.

The simulation models (so far) did not live up to their promises:

A cover story in BusinessWeek magazine in April 2009 claimed that economists mostly failed to predict the worst economic crises since the Great Depression of the 1930s (Financial crisis of 2007-08, Wikipedia)

Economists publicly disagree with each other so often that they are easy targets for standup comedians [Weintraub].

Two of the latest crises that the economists failed to predict include the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russo-Ukrainian War.

The first positivists

All economists agreed that they should explain economic phenomena and, so far as this was possible, make predictions about the future. There was, however disagreement over whether the economist should lay down principles about what was good for social welfare. One group, including Pigou (1877-1959), believed that economists could and should do this but another group, which Hicks (1904-1989) labelled “positivists” rejected normative judgements [Backhouse, 3].

- The general assumption was that humans act rational in economic decisions. Pigou’s work is positive economics insofar, as he tried to explain economy by people’s rational decisions. It became normative, when he started to promote redistribution in order to maximize total welfare; see Pigouvian redistribution.

- The founders of cost-benefit analysis (Kaldor, Hicks) in contrast, were unambiguous positivists, because they delivered a tool and not a solution. The tool allows seeing the consequences of economic decisions. The solution depends on the preferences of the decision maker and is not necessarily the one with the highest welfare [Hausman].

Comparison with physics

The following joke circulates on theoretical physics:

“Theoretical physics has basically nothing to do with reality or similar nonsense.”

In theoretical physics this sentence is an expression of self-irony, in economics the analogous sentence is less amusing. A growing part of economic theory is characterized by mathematical models, statistics and computer simulations. There is nothing wrong with this development as long as we do not forget the difference between physics and economics: A market is not a laboratory where phenomena can be repeated and investigated under controlled conditions. Mainstream economists often seem to forget a platitude: The map is not the terrain; the model is not reality. Sometimes the model becomes even more important than reality – a phenomenon which is called “model-fetishism” [Kaeser]:

|

If the model does not coincide with reality so much the worse for reality.

(Author unknown)

|

Neoclassical economics is based on strong assumptions which are often transformed into axioms – in particular the rational behaviour of the Homo Oeconomicus. The actors in a market, however, are much more willful than the molecules of a gas. Economics is closer to the social sciences than to physics and chemistry. The Dutch journalist Joris Luyendijk recently (11.Okt.2015) wrote an article in The Guardian with the provocative title: Don’t let the Nobel Prize fool you. Economics is not a science” (meaning: not a natural science). He maintains that the award glorifies economists as tellers of timeless truths, fostering hubris and leading to disaster. A Nobel Prize in economics suggests that economics is a natural science comparable to physics, a science which is able to make reliable forecasts. But the fact is that, in recent times, the forecasts of much respected economists have often driven us into the dirt. Alan Greenspan – one of the architects of the financial market deregulation and lover of mathematical models – commented after the financial crisis of 2007-08 [Kaeser]: