Indian Sources of Hellenistic Ethics

B.Contestabile First version 2008 Last Version 2023

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2.1 Cyrus (600-530 BC) and Darius I (550–486 BC)

2.2 Buddha (6th/5th century BC)

2.3 Socrates (469-399 BC)

3.1 Definition

3.2 Alexander the Great (356-323 BC)

3.3 Greco-Buddhism (ca.300 BC-400 AD)

4.1 Cynicism (from ca.400 BC)

4.2 Pyrrhonism (from ca.320 BC)

4.3 Epicureanism (from ca.310 BC)

4.4 Stoicism (from ca.300 BC)

5. Conclusion

Starting point

The cultural transfer between East and West existed within the Persian Empire during and after the time of Buddha (6th/5th century BC) and Socrates (469-399 BC). For a period of about a thousand years – from the invasion of Darius I to the sack of Rome by the Goths – India was in more or less constant communication with the West [McEvilley, 1].

Type of Problem

Was Hellenistic ethics influenced by Indian philosophy?

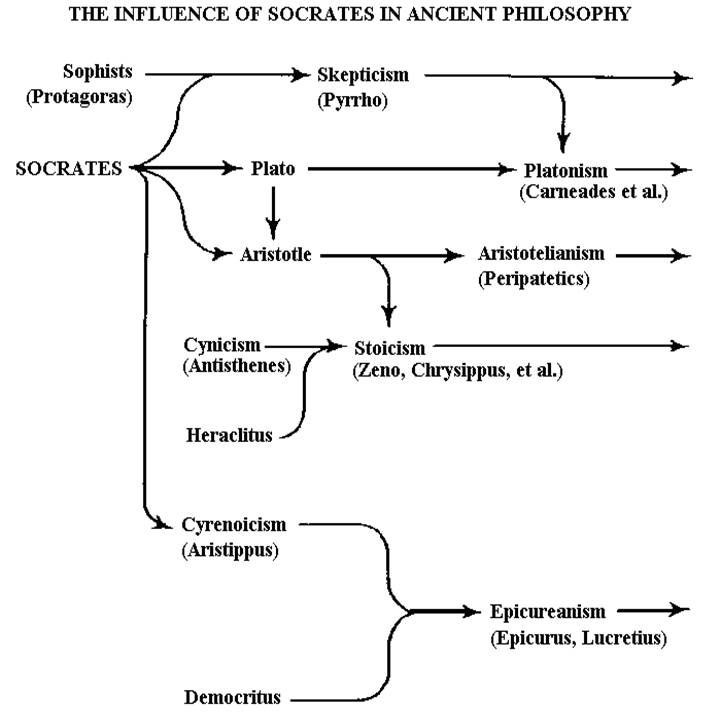

There is reason to believe that Socrates was influenced by Indian ascetics who traveled along trade routes from Central Asia to Greece. Some striking similarities exist between Socrates’ way of living and the one of Indian Sramanas. Socrates in turn had an (indirect) influence on virtually every form of Hellenistic ethics.

Cynicism

The Indian sect of Gymnosophists exerted considerable influence in Greek literature and acted as models to Cynics. Two traditions deal with encounters between them and Alexander the Great [Bosman, 175-176]. Diogenes of Sinope’s ascetic practice was probably derived from India.

Pyrrhonism

Pyrrho went with Alexander the Great to Central Asia and India during the Greek invasion and conquest of the Persian Empire in 334–324 BC [Vukomanovic, 164]. According to Diogenes Laertius Pyrrho was led to “adopt” concepts of Indian philosophy because of his contacts in India. Christopher Beckwith advances the thesis that Pyrrho based his ideas on the teachings of early Buddhism [Beckwith, 13-21, 26-32].

Epicureanism

Buddhism and Epicureanism, both define the desired state as calm, safety, and absence of pain. The great interest of both in analyzing the world and the mental and physical structure of human beings is meant to teach humans how to minimize their pain. That is the reason for making the activity of teaching a primary aim and making ignorance a primary fault [Scharfstein, 202]. The hypothesis of a Buddhist influence on Epicureanism is based on similarities.

Stoicism

Zeno of Citium, the alleged founder of Stoic philosophy, was a Samkhyin, i.e. he taught in Athens a finished philosophical system that came from India. Most likely Heraclitus of Ephesus was already a Samkhyin, because Zeno adopted his materialistic theory of physics [Baus 2010, 13]. Furthermore the Stoic reliance upon the Cynic ethics – which itself markedly resembles some forms of Indian asceticism – had been widely acknowledged in Laërtius time [Vukomanovic, 166].

Starting point

The cultural transfer between East and West existed within the Persian Empire during and after the time of Buddha (6th/5th century BC) and Socrates (469-399 BC). For a period of about a thousand years – from the invasion of Darius I to the sack of Rome by the Goths – India was in more or less constant communication with the West [McEvilley, 1].

Type of Problem

Was Hellenistic ethics influenced by Indian philosophy?

2.1 Cyrus (600-530 BC) and Darius I (550-486 BC).

Origin of philosophy

Philosophy has an international and multicultural origin with influences from Indo-Europe (Greeks and Indo-Aryans), Near East (Mesopotamian culture), the Orient (Phoenician trade, Babylonian mathematics and astronomy). All these influences came together in the Persian Empire [McEvilley, 1-6] [Conger, 106].

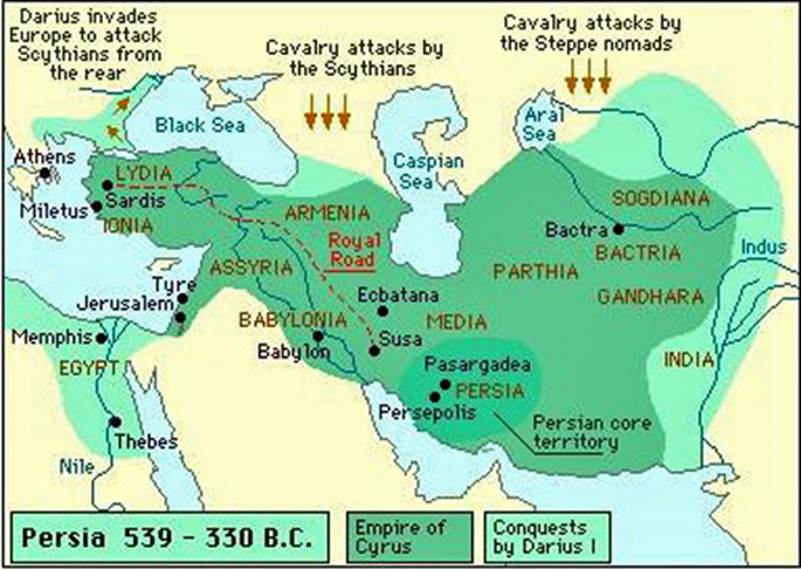

In the sixth century BC direct Greek-Indian contacts occurred in the Persian Empire which was erected on the ruins of the (Neo-)Assyrian Empire (…) Almost at once the Persian kings, extended their realm in both directions, mounted wars of conquest against the Greek border on the West and the Indian border on the Southeast. At the time of Cyrus the Great – founder of the Achaemenic Empire – the Ionian Greek city states of Asia minor where the pre-Socratic philosophers would very soon be active were brought under Persian rule. In virtually the same years, Bactria, the area just north of the Hindu Kush, and Gandhara, the area just south of it, were annexed to the Persian Empire. [McEvilley, 6-7].

For about a generation and a half after Cyrus’s conquests the most advanced parts of Greece and India were in the same political entity and for a generation after Darius I, when the imperial court scene got fully underway, this relationship was even closer. During these years Greek and Indian functionaries of various types sat down together at the Persian court, where there was a growing multicultural milieu that promoted diffusion contacts [McEvilley, 6].

In 517 BC the Greek Scylax of Caryanda was sent by Darius I to explore the Indus River valley and his now-lost book Ges Periodos is the earliest known first-hand account of India by a Greek. [Kuzminski, 35-36]

The Western world and the Western civilization must be considered the product of both Greek and Indian thought, both Western philosophy and Eastern philosophies. Trade, imperialism and currents of migration allowed cultural philosophies to intermingle freely throughout India, Egypt, Greece and the ancient Near East (Thomas McEvilley, Wikipedia)

Picture from the internet (author unknown)

Pre-Socratic philosophy

The period of unimpeded contact through the medium of Persia lasted approximately from 545 till 490 BC. These dates include the heart of the brief moment of pre-Socratic philosophy. The work of Pythagoras, Heraclitus, Empedocles, Parmenides, and others falls between them. Only the work of Thales seems clearly to have preceded this period, and even before the conquest trade routes between Greece and India were open and in use. Due to these circumstances, there is a relationship between early Greek philosophy and early Indian philosophy as clear as that between, say, early Greek sculpture and Egyptian sculpture [McEvilley, 18].

- There seems to be a connection between Heraclitus (535 – 475 BC) and the Upanishadic doctrine [McEvilley, xxxi]. Heraclitus uses the same image of a changing river, as the central Buddhist doctrine of impermanence (Heraclitus, Wikipedia)

- Overall more is known about Persian relations with Greeks than with Indians, primarily since the Greeks wrote a great deal about it and the Indians, who basically did not write history in antiquity, did not (…) Pre-Socratic philosophy began at the Persian court at Susa [McEvilley, 7]. At Persepolis twenty-three nations are portrayed in the reliefs [McEvilley, 9].

- In the very heart of the pre-Socratic period there were Indians resident at the Persian court (…). The cities that lay between Greece and India were polyglot [McEvilley, 11]. In the 6th century BC Indian traders had fixed branches in Babylon.

On a side note: Babylonian mathematicians understood key concepts in geometry more than 1000 years before the Greek philosopher Pythagoras, with whom these ideas are associated [Marshall].

2.2 Buddha (6th/5th century BC).

General information

For the traditional biography and legend see Gautama Buddha.

▪ Christopher Beckwith maintains that Buddha was a Scythian (Saka):

We have no concreted datable evidence that any other wandering ascetics preceded the Buddha. The Scythians were nomads who lived in the wilderness and it is thus quite likely that Gautama himself introduced wandering asceticism to India. [Beckwith, 5-6]. Beckwith argues that Early Buddhism resulted from the Buddha’s rejection of the basic principles of Early Zoroastrianism, while Early Brahmanism represents the acceptance of those principles [Beckwith, 43].

▪ A competing thesis, maintained by Johannes Bronkhorst, says that Gotama was born, grew up and taught in areas of the eastern Gangetic basin, which had its own distinctive culture, one that was not influenced by Brahmanical social or religious ideas [Batchelor, 197].

Anti-Metaphysics

Buddhism regards itself as presenting a system of training in conduct, meditation, and understanding that constitutes a path leading to the cessation of suffering. Everything is to be subordinated to this goal. And in this connection Buddha’s teachings suggest that preoccupation with certain beliefs and ideas about the ultimate nature of the world (i.e. metaphysics) and our destiny in fact hinders our progress along this path rather than helping it. If we insist on working out exactly what to believe about the world and human destiny before beginning to follow the path of practice we will never even set out [Beckwith, 35].

In the words of Buddha:

It is as if there were a man struck by an arrow that was smeared thickly with poison; his friends and companions, his family and relatives would summon a doctor to see to the arrow. And the man might say, “I will not drew out this arrow as long as I do not know whether the man by whom I was struck was a Brahmin, a ksatriya, a vaisya or a sudra …as long as I do not know his name and his family…whether he was tall, short or of medium height…” That man would not discover these things, but that man would die [Gethin, 66].

Buddha did not deny the existence of a soul (psyche) he just denied the existence of an eternal, unchanging soul. Sectarianism and contradicting doctrines were abundant in the times of Buddha [Baus 2006, 36], a fact which may have supported the acceptance of Buddha’s metaphysical agnosticism.

Anti-Fatalism

Buddhism may have been influenced by Samkhya, the philosophy of the Indian sage Kapila [Baus 2006, 10]. Kapila – a member of the Ksatriya caste [Baus 2006, 22] – was probably born in Kapilavastu, the home town of Buddha, long time before Buddha’s ministry. Samkhya is a soteriological philosophy which maintains that suffering can be defeated by means of knowledge. In the words of Sariputra, a chief disciple of the Buddha:

“Not knowing the experience of suffering, not knowing the cause of suffering and not knowing the path to its avoidance – that is fatal ignorance”.

Samkhya – which is the philosophical basis of Yoga – is mentioned in the Arthasastra (ca. 300 BC) as one of the three oldest brahmanist philosophies [Baus 2006, 17].

Buddha strongly opposed the doctrine of Makkhali Gosala, who claimed that men cannot influence their fate [Baus 2006, 11] and he also opposed the radically skeptic and nihilistic Carvaka philosophy. His anti-fatalistic charisma could have been a major factor for the worldwide proliferation of ancient Buddhism [Baus 2006, 29, 36]. We must imagine Buddha as leader of a group and a talented debater [Baus 2006, 16] [Burton, 189].

Sramanas

Ascetism becomes more common and systematic in India with the rise of the Sramanas in the sixth century BC. (…) Sramanism was inspired by a reaction to traditional brahmanist culture as represented by the Vedas and reformed in the Upanishads. One means to respond to the hereditary privileges of the brahmans was to reject completely the customary status of “householder” adopted by males and to resort to a very simple life “in the forest”. Although the brahmans may have responded to the revolution by adding renunciation as a fourth stage of life for all, extreme forms of ascetism, such as those promoted by the Jains, arose and should be compared to the less severe monastic practices of the Buddhists. [Sick, 261]

According to Christopher Beckwith, the original meaning of the term Sramana is “Buddhist practitioner”:

- Megasthenes stresses that the Sramanas were divided into two basic forms of practice: the “rural” Sramanas, who lived out in the open, and whom he calls the “forest-dwellers”, and the “urbon” Sramanas, whom he calls the “physicians, healers”. Little attention has been paid to this bifurcation, which could have originated only when Buddhism spread outside the South Asian monsoon zone, allowing the more ascetically inclined Sramanas to live in the open all year round. In the monsoon zone the early Buddhist needed shelter during the monsoon season. Such a temporary shelter is called an arama. Individuals who practiced Buddhism, including Buddha and his followers, were called Sramanas, a term that specifically and exclusively meant “Buddhist practitioners”. [Beckwith, 68-69, 94, 102, 104]

- Unlike many Buddhist lay believers and also unlike the Brahmanas, at least some Sramanas did not themselves believe in “Hades”, and therefore did not believe in karma and rebirth. [Beckwith, 80]. The Buddha says not a word about God or about Heaven and going there, he rejects the idea of inherent personal identities (including the “soul”), and he talks about nirvana instead (…) here on earth, in this life. [Beckwith, 105]

- The Sramanas, unlike the Brahmanas, did not exclude women from their “philosophical” studies, they only excluded sex [Beckwith, 80].

- It is significant that the followers of the suicide cult are never called Sramanas “Buddhists” [Beckwith, 85].

Early Buddhism

- According to Christopher Beckwith the Trilaksana (three marks of existence) is characteristic for Early Buddhism [Beckwith, 26-32]. Exactly as with Hume, the Trilaksana negates the characteristics of God (as well as Heaven) presumably the Early Zorastrian and Early Brahmanist God: an uncaused, perfect, eternal being, in a perfect world [Beckwith, 151-152].

- A competing thesis says that the earliest examples of Buddhist teaching are four eight-verse discourses in the Pali Canon. What is immediately apparent on reading these discourses is that they are strikingly devoid of any classical Buddhist doctrines. They represent a skeptical and pragmatic ethics, in contrast to a metaphysical doctrine [Batchelor, 202-203].

Normative Buddhism

- It is now known that organized monasteries did not exist anywhere – at least outside of Central Asia – before the Saka-Kushan period, and were introduced in India quite suddenly in the first century AD. (…) The new monastic ideal contrasts very sharply with the earlier ideal, going back to the time of the Buddha himself, of the solitary, wandering “forest” Sramana and of the less ascetic, but still solitary “urban” Sramana, as described by Megasthenes. [Beckwith, 96]

- Normative Buddhism flowered in the Saka-Kushan period, when the old solitary ascetic ideal was replaced (though not completely) by the communal, organized monastic ideal [Beckwith, 104-105].

- Normative Buddhism says that the Buddha was born a prince, but after witnessing the troubles of human life he left the palace and his family to become a Sramana and a Bodhisattva. After he finally achieved his goal under the Bodhi tree, he taught the Four Noble Truths, the Eightfold Path and the Chain of Dependent Origination. His followers, members of the Sangha, were monks and nuns who mostly lived in highly distinctive structures called monasteries. [Beckwith, 170-171].

Influence on Hellenistic ethics

The influence of Socrates on Hellenistic ethics is uncontested. There are reasons to assume that Indian ascetics had an influence on Socrates (see chapter 2.3) and on virtually every school of Hellenistic ethics discussed in this paper (see chapter 4).

General information

- Socratic Problem, Biography, Philosophy (Wikipedia)

- Historical Socrates, Bibliography (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

Hypothetical influence of Indian philosophy

In his 53rd fragment Aristoxenus tells the story of a meeting between Socrates and an Indian in Athens. The fragment was transmitted to us via Eusebius of Caesarea [Gifford] and is presumably extracted from a biography of Socrates, written at the end of the 4th century BC [Lacrosse]. The mentioned meeting may be fictitious, but the influence of Indian philosophy could nevertheless have started in Socrates’ time. There is evidence that Indian ascetics traveled to Greece along a trade route (via Oxus, Caspian Sea, Kura, and Black Sea) and that they interacted at the northern end of it with Black Sea shamans [McEvilley, 10] [Conger, 104]. There are some striking similarities between Socrates’ way of living and the one of Indian Sramanas (for the latter see chapter 2.2)

Socrates exhibited many traditional signs of deeply spiritual people. He would often spend time in meditation, and sometimes would go into deep meditational trances where he did not move for hours (Symposium, 175a-b, 220c). Like Indian monks, he had great powers of enduring physical hardships (deistspirituality.com)

- Socrates let his hair grow long, Spartan-style (even while Athens and Sparta were at war) and went about barefoot and unwashed (…). He didn’t change his clothes but efficiently wore in the daytime what he covered himself with at night (…). Against the iconic tradition of a pot-belly, Socrates and his companions are described as going hungry.

- One of the things that seemed strange about Socrates is that he neither labored to earn a living, nor participated voluntarily in affairs of state. Rather, he embraced poverty and, although youths of the city kept company with him and imitated him, Socrates adamantly insisted he was not a teacher and refused all his life to take money for what he did.

- The Sramanas, unlike the Brahmanas, did not exclude women from their “philosophical” studies; they only excluded sex [Beckwith, 80]. Similarly, Socrates seemed to have a higher opinion of women than most of his companions had, speaking of “men and women,” “priests and priestesses”.

(Socrates, Stanford).

Socrates’ public discussions can be compared with the populist approach of the Sramana movement. The Sramana movement strongly opposed the philosophies which maintained the hereditary privileges of the Brahmans, and they presented their qualms to a general audience [Sick, 269]. An Indian scholar was not respected, if he was not able to contend about his doctrine. Buddha often disputed with belligerent priests of all kinds of sects [Baus 2006, 16].

Socratic statements like “No one errs or does wrong willingly or knowingly” and “Virtue – all virtue – is knowledge” are reminiscent of the rationalist Hindu philosophy Samkhya, which could be at the root of Buddhism [Baus 2006]. Socrates and Buddha both turned away from the dominating religions of their environment and focused on ethics. Buddha – similar to Socrates – was familiar with the social class of the warriors (Kshatriyas) and challenged the class of the priests (Brahmins) by his social and moral criticism. Furthermore it strikes that Pythagoras (who went to India) as well as (the Platonic) Socrates believed in reincarnation [Taliaferro, 640]. At the end of Phaedo, Socrates maintains that the soul is immortal and goes through an endless cycle of metempsychosis and, “if deemed to have lived an extremely pious life are freed and released from the regions of the earth as from a prison”.

The extent to which the Socratic method or Socratic questioning are employed to bring out definitions implicit in the interlocutors' beliefs, or to help them further their understanding, is called Maieutics (Socratic Method, Wikipedia). Etymology: Greek maieutikós of, pertaining to midwifery (dictionary.com)

The Buddha, as well, saw the practice he taught as similar to childbirth [Batchelor, 102].

The increase of knowledge and the change of lifestyle are experienced like the beginning of a new life.

The predecessor of a Socratic-type dialogue can be found in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, a key scripture to various schools of Hinduism which was composed ca.700 BC [Deussen, 389-534]. The middle part of this Upanishad consists of four conversations, in which Yajnavalkya – one of the first philosophers in recorded history and renowned for his unrivaled talent in theological debate – plays the key role not dissimilar to the role of Socrates in the dialogues of Plato” [Deussen, 444]. For a description of the living conditions at that time see [Parmeshwaranand, 392 ff].

The dialogue between King Janaka and Yajnavalkya [Deussen, 475-481] is the prototype of later dialogues between exponents of a worldly and a spiritual mindset. Examples:

- The Samaññaphala Sutta: A dialogue between King Ajatasattu and Buddha (composed ca.500 BC).

Thanissaro refers to this text as “one of the masterpieces of the Pali canon” [Thanissaro].

- The Alexander-Dandamis colloquy: A dialogue between Alexander the Great and the Gymnosophist Dandamis (composed ca.300 BC).

Diogenes Laertius reports that Pyrrho of Elis – the Greek Buddha [Beckwith] – came under the influence of the gymnosophists while travelling to India with Alexander, and on his return to Elis, imitated their habits; see chapter 4.2.

- The Milinda Panha: A dialogue between the Indo-Greek king Menander I (Pali Milinda) and the sage Nāgasena (written ca.100 BC).

There are several key portions of this text that connect it to the Greek accounts of Alexander [Sick, 271]. But it uses sources that can be traced back as far as the Samaññaphala Sutta [Sick, 273] and the Upanishads [Hinüber 2000].

Influence on Hellenistic ethics

Another early Socratic school, the Cyrenaics, was founded by one of Socrates associates and admirers, Aristippus of Cyrene, from Libya, North Africa. The Cyrenaics disparaged speculative philosophy and extolled the pleasure of the moment. But, following Aristippus, they maintained that the purest pleasure derives from self-mastery and the philosophic life. The Cyrenaic philosophy, with its understanding of the good life as enjoyment of stable pleasures, led to the development of the Epicurean school (Hellenistic Thought, Forrest Baird).

Furthermore Socrates had an influence on Skepticism, because he criticized (among others) the social class of the priests:

Socrates raises the challenge that it might be truly bad (for one’s life, for the state of one’s soul, and so on) to base one’s actions on unexamined beliefs. For all one knows, these beliefs could be false, and without investigation, one does not even aim to rid oneself of false belief. According to Socrates an unexamined life is not worth living (Skepticism, Stanford).

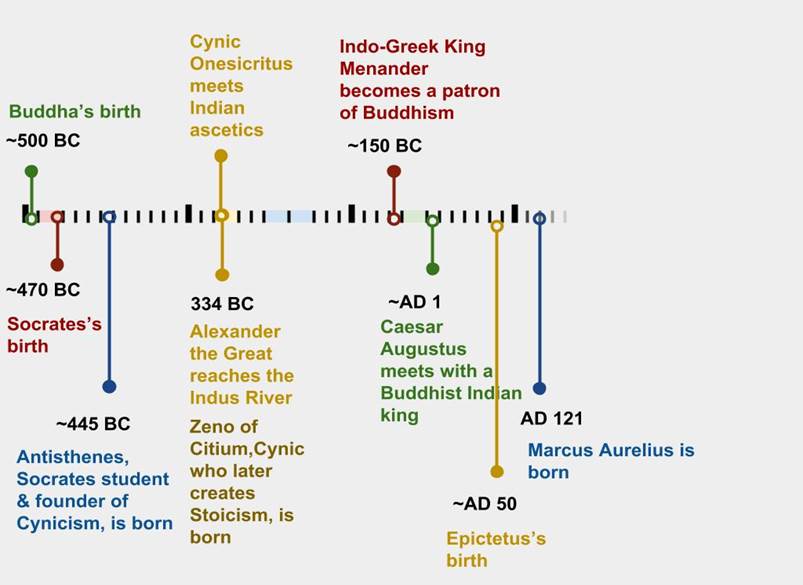

Diagram from the internet (author unknown)

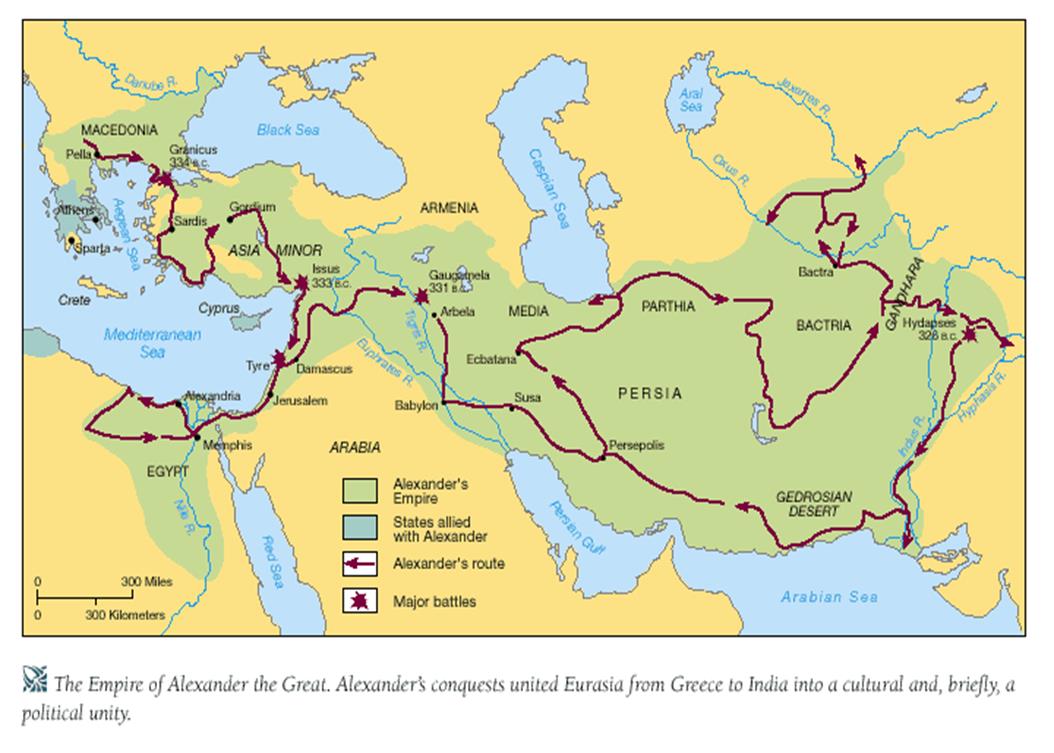

At the origin of the Hellenistic culture are Alexander the Great’s Asian campaigns.

Hellenism

The word “Hellenism” is used in several distinct ways:

1. The principal meaning is the emanation outward of culture and ideas from classical Greece to the rest of the world, with classical Greek culture and ideas either replacing local culture and ideas or amending local customs.

2. The second meaning of the word refers to the Hellenistic age or Hellenistic period of Ancient Greek (see below)

3. The third meaning is the general field of study of ancient Greek, which could include both processes just mentioned, plus scholarship since the time of the Greeks. It is also sometimes used as another word for Hellenic polytheism (Hellenism, Wikipedia).

The Hellenistic period

The most common definitions are the following:

1. The period between the death of Alexander the Great (Alexander III of Macedon) in 323 BC and the annexation of the Greek peninsula and islands by Rome in 146 BC. Although the establishment of Roman rule did not break the continuity of Hellenistic society and culture, which remained essentially unchanged until the advent of Christianity (in the 5th century), it did mark the end of Greek political independence (Hellenistic Greece, Wikipedia).

2. The period following Aristotle (384–322 BC) until the fall of the Western Roman Empire about 400 AD.

3. The intensification of the Greek influence during the time of Alexander the Great (356-323 BC) and its continuation as a cultural force up until about 400 AD (Hellenism, Wikipedia)

Hellenistic philosophy

Hellenistic philosophy is the chapter of Western philosophy that was developed in the Hellenistic period following Aristotle and ending with the beginning of Neoplatonism (Hellenistic Philosophy, Wikipedia)

For a list of the most important Hellenistic schools and philosophers see Hellenistic Philosophy.

3.2 Alexander the Great (356–323 BC)

General information

- Biography (Wikipedia)

- Indian Campaign (Wikipedia)

Below picture was taken from the internet (author unknown)

Alexander’s encounter with Indian philosophy

Alexander was interested in philosophy, possibly because during his youth, until age 16, he was tutored by Aristotle. Greek philosophers accompanied him on his Indian campaign and there are at least two traditions which report encounters between Indian sages and Alexander:

- The first, which I will refer to as the Dandamis tradition, relates to the sojourn at Taxila after the crossing of the Indus in 326 B.C. Strabo mentions Aristobulus, Onesicritus, and Nearchus as contemporary sources: Aristobulus and Nearchus describe the customs of the Indian sages while Onesicritus reports a conversation between himself and two sages mentioned by name, Calanus and Mandanis. The meeting is also reported in the Alexander historians Plutarch and Arrian [Bosman, 176]

Dandamis was a Gymnosophist.

- The second tradition relates to the trek down the Indus, after the incident with the Malli and the revolt of Sambus. Here the Indian sages, acting as political counsellors, correspond to the Brachmanes as identified by Nearchus. Plutarch mentions that the “philosophers of India” incited revolt and Alexander caught and hanged many of them. The incident may be historical, but the session in which he interrogated ten gymnosophists is no doubt fictional [Bosman, 177].

For Plutarch’s report on the latter session see Gymnosophists, Ancient accounts (Wikipedia).

A philosopher named Calanus (probably a Greek transcription of the Indian name “Kalyana”) accompanied Alexander to Persepolis, where he committed suicide on a public funeral pyre: he was probably a Jain or an Ajivika monk. Curiously, there is no reference to Buddhism in the Greek accounts (Indian Campaign, Wikipedia)

Influence on Hellenistic ethics

Indian sages influenced Greek philosophers who accompanied Alexander on his Indian campaign. Diogenes Laertius reports that Pyrrho of Elis – the Greek Buddha [Beckwith] – came under the influence of the Gymnosophists while travelling to India with Alexander, and on his return to Elis, imitated their habits (see chapter 4.2).

However, the influence of Greek and Indian philosophy was mutual.

Alexander’s legacy includes the cultural diffusion his conquests engendered, such as Greco-Buddhism (Alexander the Great, Wikipedia).

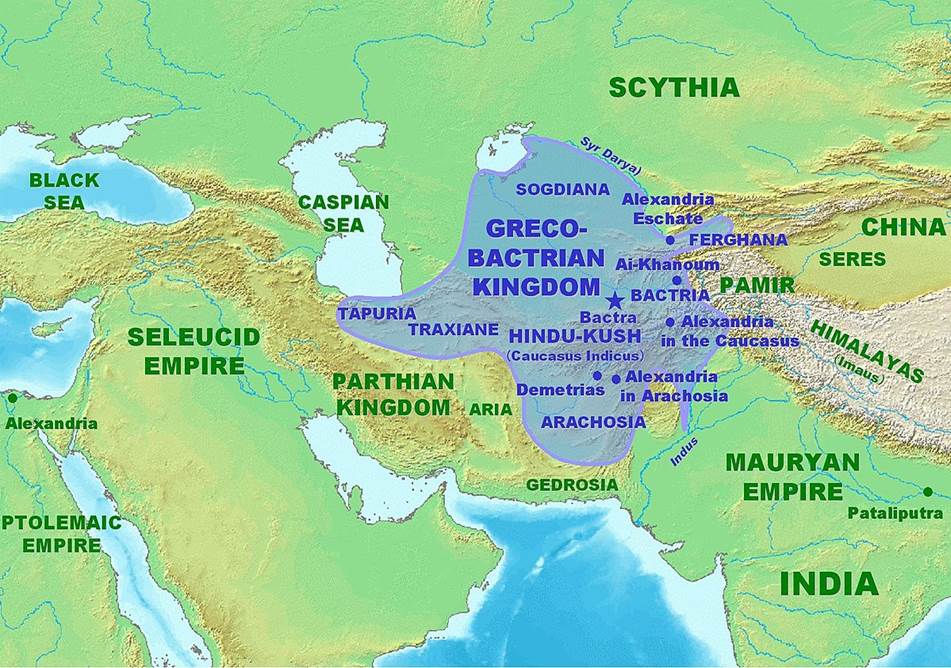

3.3 Greco-Buddhism (ca.300 BC–400 AD)

Greco-Buddhism is the cultural syncretism between Hellenistic culture and Buddhism which developed between the 4th century BC and the 5th century AD in Bactria and the Indian subcontinent (Greco-Buddhism, Wikipedia).

The interaction between Hellenism and Buddhism began when Alexander the Great began his Asian campaign in 334 BC and later came into direct contact with India, the birthplace of Buddhism. Alexander founded a number of cities in the conquered countries, which established the intensive cultural exchange and trade.

- After Alexander’s death in 323 BC, his generals founded their own kingdoms, including Seleucos I, who established the Seleucid empire, which initially maintained its expansion into India.

- The eastern part of the Seleucid Empire – Bactria – broke away as a Greco-Bactrian kingdom (3rd to 2nd century BC),

Picture from the internet (author unknown)

- The Indo-Greek kingdom (2nd to 1st century BC) was established by the expansion of the Greco-Bactrians into the Indian subcontinent (180 BC).

- Followed by the Kushan empire (1st century AD to 3rd century AD).

The resulting Hellenized form of Buddhism expanded from the 5th century to North Asia, China, Korea and Japan, and formed the basis of Mahayana Buddhism, which in turn is the origin of Zen (Greco-Buddhismus, Wikipedia).

Important patrons of Buddhism were:

- Ashoka Maurya (304-232 BC), an Indian emperor (grandson of Chandragupta, founder of the Mauryan dynasty) who ruled almost all of the Indian subcontinent from circa 269 BCE to 232 BCE.

- Menander I (165-130 BC), known in Indian Pali sources as Milinda, a king of the Indo-Greek Kingdom. According to tradition, Menander embraced the Buddhist faith, as described in the Milinda Panha, a classical Pali Buddhist text on the discussions between Milinda and the Buddhist sage Nāgasena (Menander I, Wikipedia),.

- Kanishka I (127-150 AD) was the emperor of the Kushan dynasty. His conquests and patronage of Buddhism played an important role in the development of the Silk Road, and the transmission of Mahayana Buddhism from Gandhara across the Karakoram range to China (Kanishka, Wikipedia).

In this paper we focus on some early Hellenistic schools, where an Indian influence is likely. Greco-Buddhism is beyond the scope of this paper, including Ashoka’s missionary activities on the philosophy of the Alexandrian School in the late 3rd century BC (Greco-Buddhismus).

The story of Cynicism traditionally begins with Antisthenes, (445-365 BC) who was an older contemporary of Plato and a pupil of Socrates (…) Diogenes of Sinope (412-323 BC) adopted Antisthenes teachings and embraced the ascetic way of life, adopting a lifestyle of self-sufficiency (autarkeia), austerity (askēsis), and shamelessness (anaideia). He became known as "the Dog" which is the likeliest derivation of the word "Cynic." (Cynic, Wikipedia)

▪ Thesis 1: The ascetic lifestyle of the cynics is of Indian (but not necessarily Buddhist) origin.

Various Greek philosophers, such as the Pythagoreans, had advocated simple living in the centuries preceding the Cynics (Cynicism, Wikipedia). However, pre-Socratic philosophers like Thales (624 – 546 BC) went to Egypt. Pythagoras (570 – 495 BC) and Democritus (460-370 BC) are said to have gone all the way India. Some also say that Democritus (460-370 BC) made acquaintance with the Gymnosophists in India [Vukomanovic, 164]. The Gymnosophists – to which the Calanus sect adhered – was a non-Buddhist sect [Beckwith, 64]. The Indian sages exerted considerable influence in Greek literature and acted as models to Cynics. Their original context, however, is the Macedonian conquest of India. Two traditions deal with encounters between them and Alexander the Great [Bosman, 175-176].

Furthermore there is reason to believe that Indian ascetics traveled a trade route from Central Asia to the Black Sea and interacted at the northern end of it with Black Sea shamans, ultimately influencing Greek philosophy through Diogenes of Sinope [McEvilley, 10].

▪ Thesis 2: The ascetic lifestyle of the cynics is of Buddhist origin.

Christopher Beckwith maintains that Buddha was a Scythian (Saka).

We have no concreted datable evidence that any other wandering ascetics preceded the Buddha. The Scythians were nomads who lived in the wilderness and it is thus quite likely that Gautama himself introduced wandering asceticism to India. [Beckwith, 5-6].

Asceticism became more common and systematic in India with the rise of the Sramans in the sixth century BC [Sick, 261].

According to Christopher Beckwith, the original meaning of the term Sramana is Buddhist practitioner [Beckwith, 68-69, 94, 102, 104].

The Cynics are said to have invented the idea of cosmopolitanism: when he was asked where he came from, Diogenes replied that he was "a citizen of the world” (an indication that he had travelled a lot). Although Cynicism concentrated solely on ethics, Cynic philosophy had a big impact on the Hellenistic world, ultimately becoming an important influence for Stoicism (Cynicism, Wikipedia).

Cynics lived among the people and acted as social critics; insofar they did not retreat from society. But they retreated from all kinds of dependencies.

4.2 Pyrrhonism (from ca.320 BC)

Pyrrhonism is commonly confused with (academic) skepticism in Western philosophy. But whereas (academic) skeptics maintain that there is no truth at all, Pyrrhonists leave the question open. Pyrrhonists offer no view, theory, or knowledge about the world, but recommend instead a practice, a distinct way of life, designed to suspend beliefs and ease suffering [Kuzminski, Preface].

Pyrrhonism bears a striking similarity to some Eastern non-dogmatic soteriological traditions, particularly Madhyamaka, a Mahayana school of philosophy founded by Nāgārjuna. [Kuzminski, Preface]

Because of the high degree of similarity between Madhyamaka and Pyrrhonism, Thomas McEvilley and Matthew Neale suspect that Nāgārjuna was influenced by Greek Pyrrhonist texts imported into India. The following theses suggest, however, that this could have been a return of knowledge to its origin (which was Indian):

▪ Thesis 1: Pyrrho’s philosophy was influenced by Indian (but not necessarily Buddhist) teachers.

According to McEvilley Pyrrho must have imbibed the main attitudes of his philosophy from Greek teachers, before the visit to India. The position he came to teach was clearly in the Democritean lineage. However, there remains Diogenes Laertius’ unambiguous testimony, which we have no reason to question, that Pyrrho was led to “adopt” his philosophy because of his contacts in India. McEvilley offers no evidence for downgrading Diogenes’ testimony [Kuzminski, 49]. Diogenes Laertius in his book Lives of Eminent Philosophers writes about Pyrrho’s encounter with ancient Indian thinkers and mentions even older sources [Kuzminski, 35-36] [Laertius IX 11.2]. The quadrilemma, for example, which was used in the school of Pyrrho can be found in both Greece and India before Pyrrho’s time [Kuzminski, 46] [Laertius, IX 7.2].

There are several excellent comparative studies claiming the direct influence of Indian thought on Pyrrho’s skepticism, led by Flintoff’s Pyrrho and India [Flintoff]. Giovanni Reale, in his Systems of the Hellenistic Age [Reale] has claimed that, through Pyrrho, Indian thought played a shaping, indirect role in reorienting Hellenistic ethics towards inner tranquility (ataraxia or apatheia) as the goal of life [Sharpe, 2].

▪ Thesis 2: Pyrrho’s philosophy is predominantly of early Buddhist origin.

Pyrrho went with Alexander the Great to Central Asia and India during the Greek invasion and conquest of the Persian Empire in 334–324 BC [Vukomanovic, 164]. Pyrrho’s method of suspending judgment (epoché) exhibits an amazing congruity with the original Buddhist meditation system (dhyâna) [Vukomanovic, 165].

Christopher Beckwith advances the thesis that Pyrrho based his ideas on the teachings of early Buddhism (the Trilaksana) with which he became acquainted during his time in Bactria and Gandhara [Beckwith, 13-21, 26-32]. This thesis is not new. It was first suggested by Friedrich Nietzsche who declared: “Although a Greek, Pyrrho was a Buddhist, even a Buddha.” [Batchelor, 196]. The “three characteristics” are said to apply to everything, and are central in Buddhism. But for Buddha, as for Pyrrho, their reference is exclusively to ethical or moral matters. Like Pyrrho, the Buddha did not even mention metaphysics [Beckwith, 31]. Buddha’s state of being without self-identity is equated with extinguishing passions and the peace that results from it. The result of Pyrrho’s program is exactly the same [Beckwith, 33, 93].

The Buddha, like the Pyrrhonists but unlike the Academic sceptics, took a radically undogmatic stance with regard to metaphysical or speculative beliefs (…) and concentrated instead on practices aimed at easing suffering [Kuzminski, 37]. The goal is achieved by resisting assent to any identification with extreme or dogmatic views or beliefs, whether affirmative or negative, which go beyond what is self-evident. (…) As a practical therapy and antidote to such views, both Buddhists and Pyrrhonists advocate steering a middle course through life, taking experiences at face value and avoiding unsubstantiated beliefs or conclusions. [Kuzminski, 42]

4.3 Epicureanism (from ca.310 BC)

Epicureanism is a system of philosophy based upon the teachings of the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus, founded around 307 BC. Epicurus was an atomic materialist, following in the steps of Democritus. His materialism led him to a general attack on superstition and divine intervention. Following Aristippus—about whom very little is known—Epicurus believed that the greatest good was to seek modest, sustainable "pleasure" in the form of a state of tranquility and freedom from fear (ataraxia) and absence of bodily pain (aponia) through knowledge of the workings of the world and the limits of our desires (Epicureanism, Wikipedia)

In 311-310 BC Epicurus established his first schools and in 307 BC he founded his famous Garden in Athens [Corazzon]. The thesis of a Buddhist influence on Epicurus is based on statements like the following:

|

Empty are the words of that philosopher who offers no therapy for human suffering.

For just as there is no use in medical expertise if it does not give therapy for bodily diseases, so too there is no use in philosophy if it does not expel the suffering of the soul.

Epicurus [Long and Sedley, 155]

|

Also the proposed therapy is the same:

“Suffering can be terminated by ending human desire.” (Siddharta Gautama, 490-410 BC)

“If you want to make a man happy, add not to his riches but take away his desires.” (Epicurus of Samos, 341-270 BC)

Medical analogies were commonly invoked in both Buddhist dharma [Gowans, 17-18] [Burton, 187] and Hellenistic philosophy.

Although Buddhism theoretically rejects pleasure and Epicureanism seeks it, both define the desired state as calm, safety, and absence of pain. The great interest of both in analyzing the world and the mental and physical structure of human beings is meant to teach humans how to minimize their pain. That is the reason given by both Epicureans and Buddhists for making the activity of teaching a primary aim and making ignorance a primary fault [Scharfstein, 202].

This is reminiscent of the ancient Indian Samkhya doctrine, which pursued the liberation from suffering by means of knowledge [Baus 2006, 8] and which is a possible root of Buddhism [Baus 2006, 43-44].

Buddhists and Epicureans alike advice retreat from public life and secular ambition, and alike minimize the importance of sex and family [Scharfstein, 202].

To scale down desires, the Epicureans advocated frugality, living within one’s financial means and needing little. To overcome fear, the Epicureans had two solutions:

- Forget about God, as all that exists are an infinite number of atoms arranged without any purpose in the universe. One cannot get free from fear, as long as one doesn’t understand the world and gets worried by myths. It is not possible to become truly happy without knowing nature (compare Lucretius’ De Rerum Natura).

- Seek out the company of pleasant, decent people and arrange a social contract to work towards the establishment of just laws that deter those who would harm you and your kind (…). The invention of social contract thinking on the part of the Epicureans represents one of their greatest contributions to ethical theory.

(Greek and Hellenistic Philosophy, T.O’Connor)

An early form of social contract can also be found in Buddhism (in the monastic sangha).

Examples of comparative literature:

- Roman Buddha [Ferraiolo 2010] is an article which persuasively compares Epictetus and the Buddha [Sharpe, 3].

- The Body in Spiritual Exercise [Yu 2014] considers that in both early Buddhist meditation and Epictetan askēsis, the practice of contemplating the body as it actually is (impermanent), is also a spiritual exercise to understand the phenomenal world and detach from external things [Sharpe, 6]

The beginnings of Stoicism lie with Zeno of Citium (ca. 334-263 BC) who came to Athens from Cyprus. For many years a student of the Cynic philosopher Crates, Zeno eventually founded his own philosophical school in 300 BC (Stoicism, Crandall University).

Zeno taught in the famous Stoa Poikile (the painted porch) in Athens. He combined the cynical doctrine with concepts of Heraklit and Aristoteles (Zeno of Citium).

Zeno was succeeded as head of the school by Cleanthes and Cleanthes by Chrysippus. According to Diogenes Laertius (not to be confused with Diogenes of Sinope) these three early Stoics wrote many works, but nothing except fragments have survived. Their works were still available, however, to Laertius in the third century AD. Laertius’ summary of Stoic philosophy [Laertius, 149, 195, 217, 225] is the best source of information for early Stoicism. (Stoicism, Crandall University)

There are striking similarities between the Stoic and the ancient Indian cosmology. Stoicism, just like Hinduism and Buddhism does not posit a beginning or end to the Universe. It considers all existence as cyclic, the cosmos as eternally self-creating and self-destroying (Stoicism, Wikipedia).

▪ Thesis 1: Stoicism was inspired by the Samkhya doctrine of the Indian philosopher Kapila [Baus 2006, 206-221].

Zeno of Citium, the alleged founder of Stoic philosophy, was a Samkhyin, i.e. he taught in Athens a finished philosophical system that came from India. Most likely Heraclitus of Ephesus was already a Samkhyin, because Zeno adopted his materialistic theory of physics [Baus 2010, 13].

Samkhya is strongly dualist and atheist. It regards the universe as consisting of two independent realities, puruṣa and prakṛiti.

- Purusha is pure consciousness absolute, eternal and subject to no change. It is neither a product of evolution, nor the cause. Purusha dwells in all beings as Atman.

- Prakriti (nature or matter) is the unconscious and unintelligent principle. The mind belongs to the physical world and is conscious only to the extent it receives illumination from purusha (Samkhya, Wikipedia).

Evolution is an interaction of these two realities.

Similarly, the Stoics believed that there are two organizing principles in the universe: active intelligence and passive matter. Inanimate objects are infused only with the passive principle, while living organisms also carry the active one, and human beings have enough of it to actually acquire the ability to reason (How to be a Stoic by Massimo Pigliucci)

▪ Thesis 2: Stoicism was inspired by the Advaita Vedanta whose roots trace back to the oldest Upanishads (800-700 BC).

The Advaita Vedanta philosopher Adi Shankara called Samkhya the principal opponent of the Vedanta:

- Samkhya maintained that the puruṣa cannot be regarded as the source of inanimate world, because an intelligent principle cannot transform itself into the unconscious world (Samkhya, Wikipedia). It is the unintelligent prakriti which creates the universe (Prakriti, Wikipedia).

- Advaita Vedanta, in contrast, maintained that only the intelligent Brahman can create the universe (Samkhya, Wikipedia). Brahman is the origin and end of all things, material and spiritual (Brahman, Wikipedia).

Stoicism, similar to the Advaita Vedanta, asserts that the universe is a single pantheistic god, but one which is also a material substance. The active part of god (intelligence, reason, logos), provides form and motion to (passive) matter, and is the origin of the elements, life, and human rationality (Stoic Physics, Wikipedia).

The Stoics argued that the mind (or soul) must be something corporeal and something that obeys the laws of physics (Stoic Philosophy of Mind).

Regarding the mind-body problem the monistic views of Advaita Vedanta and Stoicism are closer to contemporary cognitive science than the dualistic view of Samkhya.

▪ Thesis 3: Buddhist thought had an indirect influence on Stoicism, first through Cynic contact with the East and later through trades routes [DuBay].

The Stoic reliance upon the Cynic ethics (which itself markedly resembles some forms of Indian asceticism) had been widely acknowledged in Laërtius time [Vukomanovic, 166]

Picture from [DuBay]

Concerning Thesis 3 there are remarkable parallels between

- the Stoics’ descriptions of unhappiness and its causes, with the Buddhist kleśas (ignorance, attachment, aversion)

- the Buddhist conception of what it is we are working on when we undertake meditative practice, and the Stoic philosophy of mind (pathē as reflecting false evaluative assessments of self and world).

- the way that Buddhist meditation and the Stoic askēseis are clearly, undoubtedly recommended and illustrated.

[Sharpe, 6]

Le Retour sur Soi [Laurentiu 2008] compares Roman Stoicism and Zen [Sharpe, 3].

With regard to the societal function the original Buddhism is certainly closer to early Stoicism (ca. 300-180 BC) than to late/Roman Stoicism (ca. 27 BC-180 AD):

Second-century Stoicism set the standards for acceptable behavior and provided justification not only for traditional Roman mores, but for Roman rule. This represents a drastic change from the values of the Early Stoa [Francis]:

- Roman Stoicism preached "restraint and conformity".

- The original Stoa was a center of "dissident asceticism and social radicalism".

Within four centuries a dissident philosophy with a high affinity to Cynicism was transformed into a tool for imperialistic expansion. Stoicism, which started as a back-to-nature philosophy, turned into a cornerstone of Roman militarism.

Was Hellenistic ethics influenced by Indian philosophy?

Socrates

There is reason to believe that Socrates was influenced by Indian ascetics who traveled along trade routes from Central Asia to Greece. Some striking similarities exist between Socrates’ way of living and the one of Indian Sramanas. Socrates in turn had an (indirect) influence on virtually every form of Hellenistic ethics.

Cynicism

The Indian sect of Gymnosophists exerted considerable influence in Greek literature and acted as models to Cynics. Two traditions deal with encounters between them and Alexander the Great [Bosman, 175-176]. Diogenes of Sinope’s ascetic practice was probably derived from India.

Pyrrhonism

Pyrrho went with Alexander the Great to Central Asia and India during the Greek invasion and conquest of the Persian Empire in 334–324 BC [Vukomanovic, 164]. According to Diogenes Laertius Pyrrho was led to “adopt” concepts of Indian philosophy because of his contacts in India. Christopher Beckwith advances the thesis that Pyrrho based his ideas on the teachings of early Buddhism [Beckwith, 13-21, 26-32].

Epicureanism

Buddhism and Epicureanism, both define the desired state as calm, safety, and absence of pain. The great interest of both in analyzing the world and the mental and physical structure of human beings is meant to teach humans how to minimize their pain. That is the reason for making the activity of teaching a primary aim and making ignorance a primary fault [Scharfstein, 202]. The hypothesis of a Buddhist influence on Epicureanism is based on similarities.

Stoicism

Zeno of Citium, the alleged founder of Stoic philosophy, was a Samkhyin, i.e. he taught in Athens a finished philosophical system that came from India. Most likely Heraclitus of Ephesus was already a Samkhyin because Zeno adopted his materialistic theory of physics [Baus 2010, 13]. Furthermore, the Stoic reliance upon the Cynic ethics – which itself markedly resembles some forms of Indian asceticism – had been widely acknowledged in Laërtius time [Vukomanovic, 166].

1. Batchelor, Stephen (2012), A Secular Buddhism, Journal of Global Buddhism 13, 87-107, American Theological Library Association

2. Baus Lothar (2006), Die Philosophie des Buddha, in Buddhismus und Stoizismus: Zwei nahverwandte Philosophien und ihr gemeinsamer Ursprung in der Samkhya-Lehre, II. Auflage, Asclepios Edition, Homburg

3. Baus Lothar (2010), Der stoische Weise – ein Materialist, Asclepios Edition, Homburg

4. Beckwith Christopher I. (2015), Greek Buddha: Pyrrho's Encounter with Early Buddhism in Central Asia, Princeton University Press, Princeton

5. Bosman Philip (2010), The Gymnosophist Riddle Contest: A Cynic Text?, University of South Africa

6. Burton David (2010), Curing Diseases of Belief and Desire, Buddhist Philosophical Therapy, in Philosophy as Therapeia, Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements, Vol. 66: 187-218, Cambridge University Press, UK

7. Conger George P. (1952), Did India Influence Early Greek Philosophies?, Philosophy East and West , Vol. 2, No. 2, 102-128, University of Hawaii Press

8. Corazzon Raul (2022), Ontology, Its Role in Modern Philosophy, available from www.ontology.co/essays/hellenistic-philosophers.pdf

9. Deussen Paul (1897), Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Part 1, Translated by V.M.Bedekar and G.B.Palsule, Motilal Banarsidass, Dehli 1980

10. DuBay Dave (2017), Did Buddhism influence Stoicism?

11. Ferraiolo William (2010), Roman Buddha, in Western Buddhist Review vol. 5

12. Flintoff Everard (1980), Pyrrho and India, Phronesis, Vol.25, No.1, 88-108, Brill Publishers

13. Francis James A. (1995), Subversive Virtue, Asceticism and Authority in the Second-Century Pagan World, Pennsylvania State University Press

14. Gethin, Rupert (1998), Foundations of Buddhism, Oxford University Press

15. Gifford E.H. (1903), Eusebius of Caesarea: Praeparatio Evangelica, Book 11, available from www.tertullian.org/fathers

16. Gowans Christopher (2010), Medical Analogies in Buddhist and Hellenistic Thought: Tranquillity and Anger, Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplement 85, Vol.66: 119-135, Cambridge University Press, UK

17. Hinüber, Oskar von (1996/2000), A Handbook of Pāli Literature, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

18. Kapstein Matthew (2013), Stoics and Bodhisattvas, in Philosophy as a Way of Life, 99-115, Wiley Blackwell, UK

19. Kuzminski Adrian (2008), Pyrrhonism: How the Ancient Greeks Reinvented Buddhism, Lexington Books, Lanham, 2008.

21. Laertius Diogenes (1925), Lives of Eminent Philosophers, William Heinemann, London

22. Laurentiu Andrei (2008), Le retour sur soi : Stoïcisme et bouddhisme zen, Nagoya (Japon), in Origins and possibilities, 123-139.

23. Long A. and Sedley D. (1987), The Hellenistic Philosophers, Cambridge University Press, UK

24. Marshall Michael (2021), Geometry of triangles was in use long before Pythagoras, New Scientist, 14 August, p.23

25. McEvilley Thomas (2001), The Shape of Ancient Thought. Comparative Studies in Greek and Indian Philosophies, New York, Allworth Press

26. Parmeshwaranand Swami (2000), Encyclopaedic Dictionary of Upanisads, Vol.2 (L-R), Sarup & Sons, New Dehli

27. Reale Giovanni (1985), The Systems of the Hellenistic Age, translated by Catan, John R. (1st ed.), Albany, New York.

28. Scharfstein Ben-Ami (1998), A Comparative History of World Philosophy, State University of New York Press

29. Sharpe Matthew and Leesa Davis (2018), Notes towards a comparison of Buddhism and Stoicism as Lived Philosophies, Deakin University, Melbourne, Australia

30. Sick David H. (2007), When Socrates met the Buddha: Greek and Indian dialectic in Hellenistic Bactria and India. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 17:253-278.

31. Soni Jayandra (2010), Patañjali’s Yoga as Therapeia, Royal Institute of Philosophy Supplements, Vol.66: 219-232, Cambridge University Press, UK

32. Taliaferro Charles, Paul Draper, Philip Quinn (2010), A Companion to Philosophy of Religion, John Wiley and Sons, New Jersey

33. Thanissaro Bhikkhu (2013), Samaññaphala Sutta: The Fruits of the Contemplative Life, Access to Insight (BCBS Edition)

34. Vukomanovic Milan (2017), Schopenhauer and Wittgenstein, Assessing the Buddhist Influences on their Conceptions of Ethics

35. Yu Jiangxia (2014), The Body in Spiritual Exercise: A Comparative Study between Epictetan Askēsis and early Buddhist Meditation, Asian Philosophy, Vol 24, No 2, 158-177