Population Ethics – A Compromise Theory

B.Contestabile First version 2014 Last version 2022

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Notions of a Life Worth Living

2.1 Overview

2.2 Reverting the Better-Than Relation

2.3 Normative Considerations

3. The Compensation of Quality by Quantity

3.1 Linear Metric

3.2 Non-Linear Metric

3.3 Comparison with Sider’s Principle

3.4 Normative Considerations

4. Conclusion

Starting point

The Mere Addition Paradox was identified by Derek Parfit [Parfit 1984, Chapter 19]. It is characterized by the so-called Repugnant Conclusion, which says that (measured by the value of total welfare)

- a large population with a minimal average welfare can be ethically better than

- a small population with a high average welfare.

For a description and analysis see On the Buddhist Truths and the Paradoxes in Population Ethics.

Type of problem

A possible approach to remove the Repugnant Conclusion consists in revising the classical utilitarian notion of a life worth living [Stanford, chapter 2.4]. It turns out, however, that such revisions produce new counter-intuitive results. Gustav Arrhenius’ impossibility theorem of population ethics casts doubts on the whole project of finding a normative theory that coheres with our considered moral beliefs [Arrhenius, 265] [Spears].

Result

The proposed solution separates the axiologies (rankings) for the amount and distribution of welfare. A population can be better with regard to the internal distribution of welfare, but worse with regard to the amount of welfare (and vice-versa). Axiologies for the distribution of welfare are investigated in theories of justice. The focus of this paper is on the amount of welfare.

The Repugnant Conclusion can be avoided by a non-linear aggregation of qualities of life, which makes it impossible to replace very high qualities by very low qualities. Linear scales are not God-given; they stem from economics, where welfare can be added like amounts of money. Population ethics, in contrast, deals with general welfare and the hedonic scale has to be adapted to the corresponding intuitions.

The proposed solution represents a compromise in the conflict between quantity and quality, respectively expansionism and perfectionism. A compromise does not have the normative force of a mathematical proof. But the same is true, for example, with prioritarian welfare functions and progressive tax tables.

The solution for populations with negative welfare is analogous (but not symmetric) to the one for positive welfare. There is an asymmetry between happy and suffering populations.

Starting point

The Mere Addition Paradox was identified by Derek Parfit [Parfit 1984, Chapter 19]. It is characterized by the so-called Repugnant Conclusion, which says that (measured by the value of total welfare)

- a large population with a minimal average welfare can be ethically better than

- a small population with a high average welfare.

For a description and analysis see On the Buddhist Truths and the Paradoxes in Population Ethics.

Type of problem

A possible approach to remove the Repugnant Conclusion consists in revising the classical utilitarian notion of a life worth living [Stanford, chapter 2.4]. It turns out, however, that such revisions produce new counter-intuitive results. Gustav Arrhenius’ impossibility theorem of population ethics casts doubts on the whole project of finding a normative theory that coheres with our considered moral beliefs [Arrhenius, 265] [Spears].

2. Notions of a Life Worth Living

Semantics

For the purpose of this paper we can treat the terms happiness, (positive) welfare, quality of life and life satisfaction as synonyms.

The term suffering accordingly stands for uncompensated suffering [Fricke, 18] and is a synonym for negative welfare.

In the context of population ethics we use the term axiology for the combination of

- a structure of the hedonic scale (linear or non-linear), including a notion of the life worth living and

- a rule for aggregating welfare

Major notions

Changing the notion of a life worth living has a profound impact on the “better than” relation in population ethics and on the production of repugnant conclusions in particular. In order to investigate this impact we consider the notion of a life worth living as a parameter (like average welfare and population size). The major notions are the following:

▪ Extreme asymmetry

o every life is worth living (i.e. non-existence is the worst case)

o no life is worth living (i.e. non-existence is the best case)

▪ Moderate asymmetry

o a life is worth living if it reaches a certain level of happiness or

o a life is worth living if it does not fall below a certain level of suffering.

▪ Symmetry corresponds to the classical utilitarian definition of a life worth living. According to this definition there is a level of welfare, at which the value of a life is neutral [Broome, 142]. Above this level a life is worth living, below it is not worth living. A neutral life has the value zero on the hedonic scale [Broome, 257].

Following the major notions of a life worth living in more detail:

Extreme asymmetry

Intuitions about non-existence are driven by the interest to avoid suffering/frustration and the (conflicting) interest to survive [Contestabile 2010, 109-111].

- The intuition that suffering has a higher moral value than non-existence is e.g. defended in hospitals, where the prime interest is to avoid death. Since these hospitals do not know lives with negative welfare, death is given the value zero (see Quality-adjusted life year, Wikipedia). Even the most horrible life is considered to be worthy of preservation, a conclusion which is repugnant for many people (Fig.1, left hand side) [Contestabile 2014, 299-300].

- The complete opposite can be found in negative preference utilitarianism, where even an almost perfect life is not worth living. This is called the Reverse Repugnant Conclusion (Fig 1, right hand side).

Fig.1

The value given to non-existence determines the kind of happiness that is pursued [Contestabile 2010, 107]:

- If non-existence is associated with the worst case, then it makes sense to pursue the biological kind of happiness and strive for immortality.

- If non-existence is associated with the best case, then it makes sense to pursue the meditative kind of happiness and eliminate desires.

Above axiologies entail two Repugnant Conclusions that have to do with the relation between quantity and quality.

1. If the hospital axiology is applied to population ethics, then every life has a positive sign, so that there are only populations with positive totals (Fig.1, left hand side). This axiology is characterized by an extreme version of the (positive) Repugnant Conclusion (Fig.2, left hand side).

2. The mirror image of this axiology can be found in negative preference utilitarianism, where the prime interest is to avoid frustrations [Contestabile 2014, 307-308]. Every life has a negative sign, so that there are only populations with negative totals (Fig.1, right hand side). This axiology is characterized by an extreme version of the Negative Repugnant Conclusion (Fig.2, right hand side) [Broome, 213-214].

Fig.2

Moderate Asymmetry

Attempts have been made to mitigate the Repugnant Conclusions:

- To ease the discomfort of the Repugnant Conclusion, one could raise the notion of a life worth living (the neutral level) to a reasonably good quality of life [Broome, 213]. In this case the Repugnant Conclusion is mitigated, but the Negative Repugnant Conclusion aggravated.

- If, conversely, an axiology tolerates a certain level of suffering by giving it a positive sign, then the Negative Repugnant Conclusion is mitigated, but the Repugnant Conclusion aggravated.

Symmetry

In classical utilitarianism happy lives have a positive sign and suffering lives a negative sign. As a consequence both kinds of Repugnant Conclusions apply. The classical utilitarian setting in Fig.3 avoids the aggravated forms of the Repugnant Conclusions and represents a kind of compromise or equilibrium [Broome, 213-214, 264].

Fig.3

The hedonic definition of a life worth living is a controversial matter. However, in above diagrams the term happiness stands for life satisfaction (satisfaction with life as a whole) and not merely for pleasure, i.e. it entails a cognitive evaluation and not merely an affect. Furthermore it is a subjective judgment and not an imposed norm. The participant of a survey (and not an ethical committee) decides if his/her life is not worth living. In the latter case he/she can express that with a negative sign.

2.2 Reverting the Better-Than Relation

Repugnant conclusions can be removed by changing the notion of a life worth living.

Repugnant Conclusion: Fig.4

Within the hospital axiology B is better than A, because total welfare is greater. If the notion of a neutral life is changed from N1 to N2 (dashed line), then A is better than B. The welfare of B becomes 0, because the positive welfare (upper half of B) is now canceled by the new negative welfare (lower half of B).

Fig.4

Negative Repugnant Conclusion: Fig.5

Within negative preference utilitarianism C is worse than A, because the total negative welfare is greater. If the notion of a neutral life is changed from N1 to N2 (dashed line), then A is worse than C, because the negative welfare (lower part of C) is now canceled by the new positive welfare (upper half of C).

Fig.5

Changing the notion of a life worth living is a very efficient way to circumvent the conflict between quantity and quality. By appropriately changing this notion one of the two populations to be compared simply “disappears”, i.e. its welfare is set to zero and the “better than” relation is reverted. The decision if A is considered to be better than B, B better than A, or A equivalent to B, depends entirely on the notion of a life worth living.

Is there a normative criterion to fix the notion of a life worth living?

Ethical intuitionism

At minimum, ethical intuitionism is the thesis that our intuitive awareness of value, or intuitive knowledge of evaluative facts, forms the foundation of our ethical knowledge (Ethical intuitionism, Wikipedia).

“Our” intuitive awareness of value can only be the awareness of a majority, and not the awareness of everyone. In the conflict between the life-affirmers and the life-deniers the latter succumb, because the former have a better biological fitness. Our intuitions are shaped by biological forces. As a consequence, the hospital axiology is popular and negative preference utilitarianism is completely discarded (Fig.1).

In the hospital axiology the language is changed in such a way that states of suffering are called states of low (but still positive) quality. It is assumed that the will to live creates positive emotions, which compensate suffering. But that is a gross simplification. Sometimes it is more realistic to describe a patient’s situation by a choice between the following two evils:

- The suffering caused by illness, injuries, age-related morbidity etc.

- The suffering caused by the imagination of a painful death and non-existence

And sometimes there is a mixture and dynamic change between the patient’s evaluations.

The tolerance of suffering makes sense in a “biological” axiology, which assigns the maximum negative value to non-existence. The biological axiology is driven by the interest to survive under all circumstances. It is, for example, represented by religious physicians who consider life to be holy. Genesis 9:7 represents unconditional life-affirmation and leads to a correspondingly expansive populations ethics:

“As for you, be fruitful and increase in number; multiply on the earth and increase upon it."

In contrast, negative preference utilitarianism does not recommend “being fruitful and increasing in number” at all. The symmetric force to the (Nietzschean) will to live is the Hindu will to leave the cycle of (genetic) reincarnation. Changing the notion of a life worth living has dramatic consequences and demonstrates that language is a tool and serves a purpose. Wittgenstein may have been the first philosopher who investigated how different languages mirror different forms of life.

Normative compromise

A possible normative criterion is the equal treatment of the Repugnant Conclusions as depicted in chapter 2.1. If we fix the notion of a life worth living according to the symmetry-criterion, then the interests of the life-affirmers (hospital axiology) and the life-deniers (negative preference utilitarianism) are equally considered. In the following we adopt the classical utilitarian notion of a life worth living, because it covers both types of Repugnant Conclusions (positive and negative). If we have a solution for both types, then we can apply it to all notions of a life worth living discussed in chapter 2. We start with the assumption that the hedonic scale is signed and linear (like Table 2, column 2) and later introduce non-linear scales (chapter 3.2).

Table 2

|

Scale |

Signed Scale

|

Description adapted from [Anderson] |

|

|

10 |

+5 |

happy |

+1 |

|

9 |

+4 |

“ |

+1 |

|

8 |

+3 |

“ |

+1 |

|

7 |

+2 |

“ |

+1 |

|

6 |

+1 |

“ |

+1 |

|

5 |

0 |

neutral |

0 |

|

4 |

-1 |

suffering |

-1 |

|

3 |

-2 |

“ |

-1 |

|

2 |

-3 |

“ |

-1 |

|

1 |

-4 |

“ |

-1 |

|

0 |

-5 |

“ |

-1 |

As soon as the notion of a life worth living is fixed, we can focus on two basic questions:

1. Is the total amount of welfare positive or negative?

a. For an analytical study see The Denial of the World from an Impartial View

b. For an empirical study see Is There a Predominance of Suffering?

2. To what extent can quality be compensated by quantity?

a. Within the life-affirmers there is a conflict between perfectionists and expansionists.

b. Within the life-deniers there is a conflict between perfectionists and contractionists.

Perfectionists prefer average utilitarianism, expansionists and contractionists prefer total utilitarianism.

In chapter 3 we investigate these conflicts in more detail:

3. The Compensation of Quality by Quantity

The Repugnant Conclusion

Given total utilitarianism and Table 2

- 1 person with the maximum positive quality of life (+5 points) can be replaced by

- 5 persons with the minimum positive quality of life (+1 point)

because total welfare is the same (see Table 3). This is the root of the Repugnant Conclusion.

Table 3

|

|

can be replaced by

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

The Negative Repugnant Conclusion

Given total utilitarianism and Table 2

- 5 persons with a minimum negative quality of life (-1 point) can be replaced by

- 1 person with the maximum negative quality of life (-5 points)

because total negative welfare is the same (see Table 4). This is the root of the Negative Repugnant Conclusion.

Table 4

|

can be replaced by

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

Quantity versus quality

- In the area of positive welfare a linear metric (total utilitarianism) promotes population growth at the cost of the quality of life (Repugnant Conclusion).

- Average utilitarianism avoids the Repugnant Conclusion, but it only accounts for quality and completely discards quantity.

The theory promoted in this paper holds that quantity and quality both count, but that losses in quality cannot always be outweighed by increases in quantity. A non-linear metric prevents the Repugnant Conclusion as well as average utilitarianism, but without completely discarding quantity. It accounts for quality by devaluating low qualities, but the devaluation is incomplete. Insofar it represents a compromise between perfectionists and expansionists [Arrhenius, 58].

A compromise between quantity and quality accords with the intuitions of the majority:

An empirical study found that people take into account both the average level (averagism) and the total level (totalism) of happiness when evaluating populations. Participants preferred populations with greater total happiness levels when the average level remained constant and populations with greater average happiness levels when the total level remained constant. When the two principles were in conflict, participants’ preferences lay in between the recommendations of the two principles, suggesting that both are applied simultaneously [Caviola, 2].

Positive welfare

Total utilitarianism has an inflationary effect for two reasons:

- The quality of life is finite, so that the quantity has to be expanded in order to maximize welfare.

- It is easier to increase the population size than the average welfare.

The aggregation of welfare described in chapter 3.1, however, is not God-given. It stems from economics, where welfare can be added like amounts of money. In population ethics, in contrast, we have to deal with general welfare and the hedonic scale has to be adapted to the corresponding intuitions. Since research on population ethical intuitions is in an early stage [Caviola], the corresponding data are not yet available. In order to illustrate the basic idea (the devaluation of low qualities) and not to complicate matters we use an exponentiation with base = 2:

Table 5

If we apply Table 5 to the example in chapter 3.1, then 16 persons on quality level 1 are required to replace 1 person on level 5 (instead of 5 persons). Low qualities are devaluated relative to high qualities. Persons on quality level 0 (neutral lives) don’t count. It is impossible to replace lives with positive value by neutral lives.

Comparison with total utilitarianism

Let us assume we compare the populations in Fig.6 according to the rules of total utilitarianism, using the quality levels of Table 5, column 2.

Total welfare A = (quality-level 4) x (100 persons) = +400

Total welfare B = (quality-level 2) x (201 persons) = +402

B is better than A. This is a mild example of the Repugnant Conclusion.

Fig.6

And now we compare the same populations applying the devaluated qualities of Table 5, column 4

Total welfare A = (quality-level 4) x (devaluation-factor 0.5) x (100 persons) = +200

Total welfare B = (quality-level 2) x (devaluation-factor 0.125) x (201 persons) = +50.25

A is better than B, the Repugnant Conclusion has disappeared (Fig.7):

Fig.7

As a side note: It doesn’t matter if column 4 or 5 is used, because only the relative value decides about the betterness of a population.

- With col.5 one could calculate a weighted average, because the sum of all weights (percentages) equals 100%.

- The application of col.4 results in a weighted total, because the sum of all weights is greater than 100%.

Negative welfare

An analogous approach can be used to compare populations with negative total welfare. In this case the conflict between quantity and quality takes the following form:

- the interest to reduce negative total welfare (negative quantity) versus

- the interest to reduce the negative average welfare (negative quality).

The example with the Negative Repugnant Conclusion in chapter 3.1 demonstrates that it is (too) easy to replace negative quantity by negative quality. We therefore replace the linear scale by a devaluation table, which is analogous to the one above (compare Table 5 with Table 6). The symmetry is a simplification. In practice these tables have to be adapted to the intuitions of the majority [Caviola] or an ethics committee.

Table 6

For the value of the base analogous considerations apply as for the range of positive welfare.

Populations with negative total welfare occur

- in catastrophic scenarios within the classical utilitarian axiology (chapter 2.1, Fig.3 right hand side) and

- in negative utilitarianism, see Antinatalism and the Minimization of Suffering

A practical example in negative utilitarianism is the decision between

- fighting world hunger

- preventing torture

With the same amount of money many more people can be saved from starvation than from torture.

3.3 Comparison with Sider’s Principle

Definition

Sider’s principle first divides a population into two ordered sets: one set with the welfare profiles of the people with positive welfare, in order of descending welfare; and another set with the welfare profiles of the people with negative welfare, in order of ascending welfare. Sider’s principle dampens the value of the welfare of different people to different degrees depending on their place in the orderings of the positive and negative welfare profiles. The higher a person’s positive welfare relative to the welfare of others, the less dampening of the value of this person’s welfare will take place and, consequently, the more she will contribute to the value of the population. The value of the person with the highest welfare will not be dampened at all. The more negative a person’s welfare is relative to the welfare of others, the less dampening of the disvalue of this person’s welfare will take place and, consequently, the more she will detract from the value of the population. The disvalue of the person with the most negative welfare will not be dampened at all [Arrhenius, 68] [Sider].

So far our concept (Table 5 and Table 6) accords with Sider’s principle, if we replace the term dampening by the term devaluation.

Arrhenius’ criticism

Gustav Arrhenius declares Sider’s principle to be flawed [Arrhenius, 69] because of the following kind of comparison (Fig.8). Populations are devaluated according to Sider’s principle (in our case according to Table 5, column 4).

Fig.8

Populations before devaluation

Population A

Total welfare A = (quality level 4) x (20 persons) = 80

Average welfare A = (total welfare) / (40 persons) = 2

Here we apply the devaluation to each group of persons within A that has the same quality level:

Devaluated welfare A1 = (quality-level 4) x (devaluation-factor 0.5) x (20 persons) = 40

Devaluated welfare A2 = (quality-level 0) x (devaluation-factor 0.0) x (20 persons) = 0

Devaluated welfare A = 40

Population B

Total welfare B = (quality level 2) x (40 persons) = 80

Average welfare B = (total welfare) / (40 persons) = 2 (i.e. quality level 2)

Here we apply the devaluation to the average welfare of the whole population:

Devaluated welfare B = (quality-level 2) x (devaluation-factor 0.125) x (40 persons) = 10

Population C

We assume that population C has quality level 3

Total welfare C = (quality-level 3) x (40 persons) = 120

Average welfare C = (total welfare) / (40 persons) = 3

Devaluated welfare C = (quality-level 3) x (devaluation-factor 0.25) x (40 persons) = 30

Fig.9

Populations after devaluation

Before the devaluation population C has higher total welfare, higher average welfare, and it is more equal than population A. Yet, Sider’s principle would rank A as better than C [Arrhenius, 69]. This looks like a serious theoretical deficiency. But Sider’s principle can be saved, if the distribution of welfare within the population A is considered separately.

Amount and distribution of welfare

Axiologies are tools and serve a purpose. The comparison of A with C mixes two different evaluations, which serve two different purposes:

Purpose (1): Find the better population with regard to the internal distribution of welfare

Examples:

- Egalitarianism promotes equal welfare for everybody

- Maximin is a possible interpretation of Rawls’ difference principle. The ethical rank of a population is measured by the welfare of the worst-off.

Axiologies for the distribution of welfare are explored in theories of distributive justice.

On a side note:

- Utilitarianism can be interpreted as a theory of justice, although the distribution of welfare is subordinated to the maximization of welfare.

- In the context of population ethics, prioritarianism can be replaced by a non-linear metric within utilitarianism, see Antinatalism and the Minimization of Suffering. This metric can (but doesn’t have to) turn total welfare into negative territory.

Purpose (2): Find the better population with regard to the amount of welfare

Examples:

- Total utilitarianism (unweighted total), chapter 3.1

- Sider’s principle (weighted total), chapter 3.2

In our example (Fig.8 and Fig.9) the concept of justice is egalitarianism. Sider’s principle can be saved, if we consider egalitarianism separately:

(1) Ranking for the distribution of welfare: Population C is better than A, because the distribution of welfare is more equal in C.

(2) Ranking for the amount of welfare, disregarding the distribution: If the distribution in A is disregarded, it looks like B. We don’t apply Sider’s principle to the quality levels within the population (A1, A2), but only to the quality level of the whole population (average level of A1+A2 = level of B). B is ranked worse than C before and after the devaluation. The theoretical deficiency is removed.

(Side remark: If we disregard the distribution, then the comparison of populations with the same number of people is trivial. Sider’s principle becomes interesting only in the trade-off of quality against quantity).

The separation of amount and distribution not only saves Sider’s principle, it also removes the general problem how the amount should be weighed relative to the distribution. Let us consider the two extreme cases:

1. The amount of welfare overrules the distribution of welfare.

No matter how the amount of welfare is aggregated, this has the absurd implication that

- a population with an arbitrary amount welfare and an extremely unjust distribution (like the City of Omelas) is better than

- a population with the ideal distribution and a minimally lower welfare

2. The distribution of welfare overrules the amount of welfare.

No matter what kind of distribution is declared to be the ethical ideal, this has the absurd implication that

- a population with very high welfare and a minimal deviation from the ideal distribution is worse than

- a population with the ideal distribution and an very low welfare.

Example: If egalitarianism is declared to be the ideal distribution

this has the absurd implication that a population with very high welfare and some inequality is worse than a population of equally tormented people [Arrhenius, 104].

Obviously, a combined ranking requires a consensus how the amount of welfare must be weighed relative to the distribution of welfare. But why should we aim at a combined ranking at all?

Separate rankings

A separate ranking says that in Fig.8

- A is equal to B regarding the amount of welfare

- A is worse than B from an egalitarian point of view.

A combined ranking would be a loss of information. The separate ranking does not disprove Arrhenius’ impossibility theorem. But it questions the task of reconciliating all population ethical intuitions in a single index.

In the realm of economic welfare nations are ranked according to many different criteria, see List of international rankings. All these different indices complement each other. There is no need for a single overall ranking. In particular there is no need

- to combine the total amount of wealth and wealth inequality in a single index and

- to combine the total amount of income and income inequality in a single index.

Why should population ethics use a single index for the amount and distribution of general welfare?

Mathematical view

From a mathematical point of view there is no smooth transition from the function in Table 5 to the function in Table 6. Because of this discontinuity we replace the exponential functions by a power function:

Table 7

|

Scale |

Quality level x |

Revaluation x2 |

Revaluation In Percent

|

|

10 |

+5 |

52 = 25 |

45.46 |

|

9 |

+4 |

42 = 16 |

29.09 |

|

8 |

+3 |

32 = 9 |

16.36 |

|

7 |

+2 |

22 = 4 |

7.27 |

|

6 |

+1 |

12 = 1 |

1.82 |

|

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Total |

55 |

100.00 |

For negative qualities (Table 8) the revaluation is analogous.

Table 8

|

Scale |

Quality level x |

Revaluation x2 |

Revaluation In Percent

|

|

5 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

4 |

-1 |

(-1)2 = 1 |

1.82 |

|

3 |

-2 |

(-2)2 = 4 |

7.27 |

|

2 |

-3 |

(-3)2 = 9 |

16.36 |

|

1 |

-4 |

(-4)2 = 16 |

29.09 |

|

0 |

-5 |

(-5)2 = 25 |

45.46 |

|

Total |

55 |

100.00 |

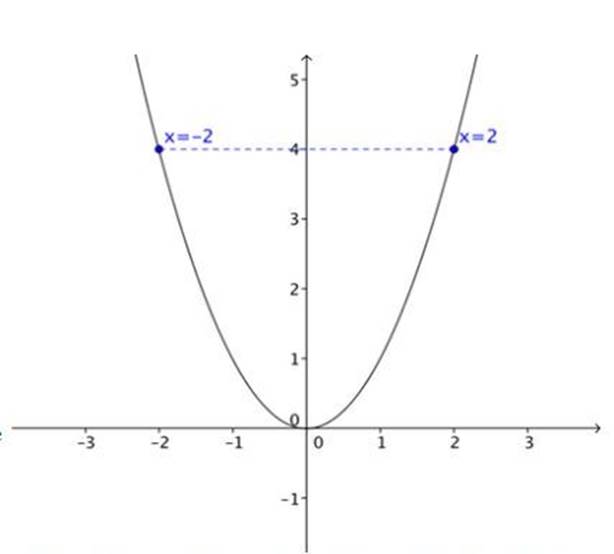

Fig.10

The following picture shows the smooth transition from negative to positive values for the power function x2.

Picture from the internet (author unknown)

The weighting of quality and quantity

In Table 7 we see under what circumstances quantity is preferred to quality.

Example: 10 (and more) persons on quality level +1 are preferred to one person on quality level +3.

With this relation

- a large country like Germany (with a 2012 population of 80.3 million) would have to be preferred to

- a small country like Denmark (with a 2012 population of 5.6 million)

although Germany was only on quality level +1 and Denmark close to quality level +3 (World Happiness Report, 30). If the majority (or an ethics committee) finds this preference repugnant, then the exponent of the power function x2 must be raised.

Note that the normative claim is restricted to the non-linearity of the metric. In practice the tables must be adapted to the intuitions of the majority (or an ethics committee). The situation can be compared to income tax tables. A vast majority of countries is committed to the normative claim that the income tax should be progressive. But there is no generally binding norm for the concrete values within the tables.

Incommensurability

The Repugnant Conclusion disappears, if the commensurability of significantly different qualities of welfare is denied [Contestabile 2010, 110]. Let us assume the term significantly different refers to the difference between very high positive welfare and very low positive welfare, as discussed in the Mere addition paradox. In this case the exponent of the power function xn can be defined in such a way that

- the welfare of a large population with very low positive welfare cannot compensate for

- the welfare of a small population with very high positive welfare.

The compensation of high quality by a large amount of low quality becomes as impossible, as if the qualities were incommensurable. However, populations with different sizes and incommensurable qualities cannot be ordered any more according to an uncontested “is better than” relation. The price for giving up commensurability is high [Contestabile 2010, 112].

Empirical findings

An empirical study found that participants’ preference for smaller over larger unhappy populations was stronger than their preference for larger over smaller happy populations. People show “asymmetric scope sensitivity” with respect to happy and unhappy population sizes. And this asymmetric scope sensitivity was more pronounced the larger the population sizes got. It is possible that this asymmetric scope sensitivity can be explained by the fact that people consider suffering more bad than they consider happiness to be good, and they are therefore particularly focused on minimizing the extent of suffering rather than maximizing the extent of happiness. An alternative hypothesis would be that our finding could be explained by the fact that people consider suffering more intense than happiness [Caviola, 38].

The symmetric examples in the previous chapters are a simplification. In practice

- quantity has more weight in happy populations than in suffering populations and

- quality has more weight in suffering populations than in happy populations.

There is a normative claim according to which the relation between happiness and suffering is asymmetric. But again, there is no generally binding norm for the concrete values within the tables.

Human rights

The axiologies discussed in this paper are forms of consequentialism and have a corresponding totalitarian potential [Knutsson]. Adherents of these axiologies, who recognize the totalitarian potential as a problem, amend their theory with human rights (as a side constraint of any attempt to improve the state of affairs). Such an anti-totalitarian ethics corresponds to a political party or movement within a democratic system.

The proposed solution separates the axiologies (rankings) for the amount and distribution of welfare. A population can be better with regard to the internal distribution of welfare, but worse with regard to the amount of welfare (and vice-versa). Axiologies for the distribution of welfare are investigated in theories of justice. The focus of this paper is on the amount of welfare.

The Repugnant Conclusion can be avoided by a non-linear aggregation of qualities of life, which makes it impossible to replace very high qualities by very low qualities. Linear scales are not God-given; they stem from economics, where welfare can be added like amounts of money. Population ethics, in contrast, deals with general welfare and the hedonic scale must be adapted to the corresponding intuitions.

The proposed solution represents a compromise in the conflict between quantity and quality, respectively expansionism and perfectionism. A compromise does not have the normative force of a mathematical proof. But the same is true, for example, with prioritarian welfare functions and progressive tax tables.

The solution for populations with negative welfare is analogous (but not symmetric) to the one for positive welfare. There is an asymmetry between happy and suffering populations.

1. Anderson Ron (2012), Human Suffering and Measures of Human Progress, Presentation for a RC55 Session of the International Sociological Association Forum in Buenos Aires, Argentina

2. Arrhenius Gustav (2000), Future Generations, A Challenge for Moral Theory, FD-Diss., Uppsala University, Dept. of Philosopy, Uppsala: University Printers

3. Broome John (2004), Weighing Lives, Oxford University Press, New York

4. Caviola Lucius et.al. (2021), Population ethical intuitions, Department of Psychology, Harvard University

5. Chalmers, D.J. (1995), Facing up to the problem of consciousness, Journal of Consciousness Studies 2, 200−219

6. Contestabile Bruno (2010), On the Buddhist Truths and the Paradoxes in Population Ethics, Contemporary Buddhism Vol.11, No.1, 103-113, Routledge, London

7. Contestabile Bruno (2014), Negative Utilitarianism and Buddhist Intuition, Contemporary Buddhism, Vol.15, Issue 2, 298–311, Routledge, London

8. Embacher Franz (2003), Mendel und die Mathematik der Vererbung, Universität Wien, available from http://homepage.univie.ac.at

9. Fehige Christoph (1998), A Pareto Principle for Possible People, in C. Fehige and U. Wessels, eds., Preferences, Berlin: Walter de Gruyter

10. Fowler Merv (1999), Buddhism: Beliefs and Practices, Sussex Academic, Brighton

11. Fricke Fabian (2002), Verschiedene Versionen des negativen Utilitarismus, Kriterion Nr.15, p.13-27

12. Hirota Dennis (2000), Toward a Contemporary Understanding of Pure Land Buddhism, State University of New York Press

13. Kleinewefers Henner (2008), Einführung in die Wohlfahrtsökonomie, Verlag W. Kohlhammer, Stuttgart

14. Knutsson Simon (2021), The world destruction argument, Inquiry, Vol.64, Issue 10, 1004-1023, Routledge, Norway

15. Parfit Derek (1984), Reasons and Persons, Clarendon Press, Oxford

16. Raju, P.T. (1992), Philosophical Traditions of India, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers, Delhi

17. Ryberg, J. (1996), “Is the Repugnant Conclusion Repugnant?”, Philosophical Papers, XXV, 161-177.

18. Sider, T. R. (1991), “Might Theory X Be a Theory of Diminishing Marginal Value?”, Analysis 51 (4), 265-271

19. Spears Dean (2019), Why Variable-Population Social Orderings Cannot Escape the Repugnant Conclusion, The University of Texas, Austin

20. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (2016), The Repugnant Conclusion

21. Starmans Christina (2015), Developing Intuitions about the Self, Dissertation, Yale University

22. Tolstoi L.N. (1882), Meine Beichte (übersetzt von R.Löwenfeld), Eugen Diederichs Verlag, 1978

23. Webster David (2005), The Philosophy of Desire in the Buddhist Pali Canon, RoutledgeCurzon, London

24. World Happiness Report (2012), Edited by John Helliwell, Richard Layard and Jeffrey Sachs, The Earth Institute, Columbia University Press, New York