Negative Utilitarianism and Justice

B.Contestabile First version 2005 Last version 2023

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2.1 Social Contract Theory

2.2 Impartiality

2.3 Rawls’ Principles

2.4 Comparison with Classical Utilitarianism

3. Negative Utilitarianism (NU)

3.1 Historical Background

3.2 Definition

3.3 Moderate NU

3.4 Comparison with Rawls’ Theory

3.5 Implementation

4. Conclusion

Starting point

Starting point of this paper is Popper’s controversial statement

“…from the moral point of view, pain cannot be outweighed by pleasure and especially not one man’s pain by another man’s pleasure” [Popper 1945/1966, 284].

This citation addresses a well-known discomfort with the classical utilitarian accumulation of suffering and happiness across different people. Parfit’s claim about compensation [Parfit, 337] and Wolf’s misery principle [Wolf, 63] agree with Popper’s intuition.

Type of problem

- Does negative utilitarianism solve the problem of compensation?

- What are the differences between negative utilitarianism and Rawls’ concept of justice?

Negative utilitarianism

Negative utilitarianism (NU) is an umbrella term for ethics which models the asymmetry between suffering and happiness [Fricke, 14]. It includes concepts that

- assign a relative priority to the avoidance of suffering

- assign an absolute priority to the avoidance of suffering

- consider non-existence to be the best possible state of affairs

In this paper we investigate compensation across different persons (inter-personal compensation). For compensation within the same person (intra-personal compensation) see Why I’m (Not) a Negative Utilitarian.

A relative priority of (the avoidance of) suffering means that happiness has moral value, but less than suffering. The moral weight of suffering can be increased by using a "compassionate" metric, so that the result is the same as in prioritarianism. The more weight is assigned to suffering, the more difficult it becomes to compensate suffering by happiness. The intuition that “global suffering cannot be compensated by happiness” turns global welfare negative, so that the maximization of happiness turns into a minimization of suffering. The rationality of this intuition is investigated in The Denial of the World from an Impartial View and Is There a Predominance of Suffering?

Absolute priority represents a border case of relative priority, where the moral weight of happiness converges towards zero. Absolute priority can be approximated by relative priority. Relative priority is the general model.

Without metaphysical assumptions the statement that no state of affairs can be better than non-existence is counter-intuitive for most people; see Negative Preference Utilitarianism.

Rawls’ theory versus negative utilitarianism

Priority of human rights:

- In negative utilitarianism it is theoretically possible to override human rights, if it serves the minimization of negative total welfare.

- In Rawls’ Theory of Justice it is impossible to override human rights, even if this principle causes the perpetuation of suffering.

Distribution of welfare among social classes:

Rawls’ difference principle accords well with the intentions of negative utilitarianism, if the term welfare is interpreted as life satisfaction.

Compensation among generations:

- In negative utilitarianism a generation may be obliged to sacrifice themselves, if it serves the long-term reduction of suffering.

- Rawls’ theory promotes the principle of intergenerational moral impartiality.

Non-contractual cases:

- In negative utilitarianism the minimization of suffering includes all sentient beings.

- Rawls’ theory lacks a principle for the protection of non-contractual cases.

Starting point

Starting point of this paper is Popper’s controversial statement

“…from the moral point of view, pain cannot be outweighed by pleasure and especially not one man’s pain by another man’s pleasure” [Popper 1945/1966, 284].

This citation addresses a well-known discomfort with the classical utilitarian accumulation of suffering and happiness across different people. Parfit’s claim about compensation [Parfit, 337] and Wolf’s misery principle [Wolf, 63] agree with Popper’s intuition.

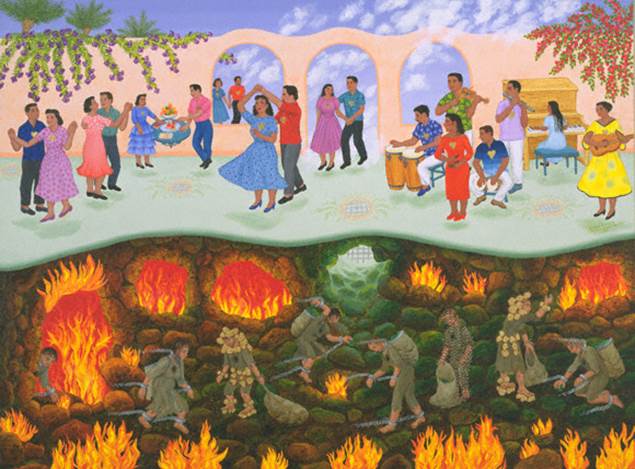

The picture below is one of the more harmless representations of heaven and hell, but it suggests that these realms exist here, on this earth, in this moment. One could argue that – although the injustice may never end – the individuals in the lower part of the picture will not suffer forever. But researchers work on life extension and the anti-aging movement dreams of immortality.

Picture from the internet (artist unknown)

Type of problem

- Does negative utilitarianism solve the problem of compensation?

- What are the differences between negative utilitarianism and Rawls’ concept of justice?

Social contract theories are theories on mutual benefit through cooperation.

Contractarians claim that moral principles derive their normative force from the idea of contract or mutual agreement. They are thus skeptical of the possibility of grounding morality or political authority in either divine will or some perfectionist ideal of the nature of humanity (contractarianism, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

If an agreement with mutual benefit can be found, it is rational to sign a corresponding contract. But contractarians don’t claim that human behavior can be described by rationality. The claim is only that rationality has a normative force in defining ethical goals. Rationality is a possible common denominator to overcome the cultural diversity of ethical norms.

- Contractarianism, which stems from the Hobbesian line of social contract thought, holds that persons are primarily self-interested, and that a rational assessment of the best strategy for attaining the maximization of their self-interest will lead them to act morally (where the moral norms are determined by the maximization of joint interest) and to consent to governmental authority. Gauthier, Narveson, or Buchanan are Hobbesian contractarians.

- Contractualism, which stems from the Kantian line of social contract thought, holds that rationality requires that we respect persons, which in turn requires that moral principles be such that they can be justified to each person. Thus, individuals are not taken to be motivated by self-interest but rather by a commitment to publicly justify the standards of morality to which each will be held. Rawls or Scanlon are Kantian contractualists

(Contractarianism, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy).

In reality social contracts may primarily be shaped by self-interest, but Rawls’ theory is normative and not descriptive [Rawls 1958, 183]. The goal is to establish an ethical ideal against which social contracts can be measured. Contractarian ideals are based on the concept of impartiality.

Origin

Kant's categorical imperative is the best known definition of an impartial moral law. But the idea of moral impartiality is much older and can be found in many religions under the term “Golden Rule” or “ethic of reciprocity. It has been speculated that empathy lies behind the prevalence of the Golden Rule.

The ancient Stoic-Skeptic tradition made a significant impact on the most prominent ethical theory of modern Europe – i.e. on Immanuel Kant’s moral philosophy. The Kantian Hellenistic ideal is originating, in my view, from the more profound and more systematic ethical teachings of the Buddhist India [Vukomanovic, 167]

The impartial observer

A contract is impartial if the principles

- do not depend on the specific interests of a single contractor or a group of contractors

- do not depend on temporary circumstances

Since politics is characterized by conflicting interests, only an impartial observer could design this kind of principles. The idea of an impartial observer was first mentioned by Adam Smith in his Theory of Moral Sentiments and later taken up by Harsanyi and Rawls.

- In his Theory of Justice Rawls used the following thought experiment to derive the conditions of an impartial contract: A contract is impartial, if it is derived from an original position in which rational contractors under a veil of ignorance decide how they wish to commit themselves to being governed in their actual lives (Justice as a Virtue, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy). Behind such a veil of ignorance all individuals are specified as rational, free, and morally equal beings. Behind the veil of ignorance, what will the rational choice be for fundamental principles of society? The only safe principles will be impartial principles, for you do not know whether you would suffer or benefit from the structure of any biased institutions.

- Rawls called this concept Justice as fairness. Justice in a strict sense would include equality of opportunity in all aspects of life. Fairness is not equivalent to justice, but represents a practicable benchmark for existing political systems.

Impartiality gets support from recent discoveries in biology. We are all, regardless of race, genetically 99.9% the same (Wikipedia, Human Genome). In other words: 99.9% of the human genes are permanently being reincarnated.

Buchanan’s anarchistic equilibrium

Buchanan’s theory questions the role of the impartial observer in establishing a social contract. There is no unique interpretation of the impartial observer. Is he/she risk-tolerant or risk-averse? The concept attempts to circumvent the problem of incomparable individual utilities, but now the problem reappears in the ambiguous characteristics of the observer.

Buchanan replaces the veil of ignorance by an anarchistic equilibrium, where people with different interests overcome anarchy by a social contract. Depending on the social status of an individual, the interest to sign such a contract is stronger or weaker.

|

I either want less corruption or more chance to participate in it!

|

- The propagation of universal solidarity can be interpreted as a strategy of the infirm (as Nietzsche did).

- On the other hand, even the rich people become weak with age and the wealthy part of the population is willing to pay a price for stability.

According to Buchanan the courts are solely mediators between the parties. They are obliged to strict neutrality and have no competence in defining justice (Ökonomische Ethik, by Roland Vaubel).

From the perspective of Rawls’original position, Buchanan’s vision of justice is rather descriptive than normative. It lacks the constituents to construct an ethical ideal.

Nozick’s liberalism

Nozick, as well as Buchanan, questions the objectivity of risk-aversion. He emphasizes the importance of property rights and promotes a minimal state. The task of the minimal state is to protect property against violence and theft, but redistribution (like Rawls’ difference principle) has no moral foundation.

From the perspective of Rawls’original position, Nozick’s vision of justice is distorted by temporary and biased interests. It does not account for differences in talent and the contingency of life stories. Similar to Buchanan’s vision, it lacks the constituents to construct an ethical ideal.

Geuss’ historical and practical approach

Raymond Geuss favors an approach to political philosophy in which one studies, history, social and economic institutions, and the real world of politics in a reflective way. He thinks that in using abstract methods in political philosophy, one will succeed merely in generalizing one's own local prejudices, and repackaging them as demands of reason. The study of history can help to counteract this natural human bias.

Rawls thinks that – quite the contrary – the interpretation of history is driven by local and temporary prejudices and that abstraction is the most promising approach to overcome the natural human bias.

Justice has several dimensions, some of which can be influenced, whereas others can’t. Rawls Theory of Justice [Rawls 1971] restricts the investigation to those dimensions that can be influenced.

Definition

1) First principle of justice: Each person is to have an equal right to the most extensive total system of equal basic liberties compatible with a similar system of liberty for all.

2) Second principle of justice: Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are both

a) attached to offices and positions open to all under conditions of fair equality of opportunity and

b) to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged, consistent with the just savings principle

(Distributive Justice, Wikipedia)

“Just savings” is what a generation owes its descendants:

- immaterial values: just institutions, cultural values

- in economic terms: capital, factories, machines, knowledge, techniques, skills, natural resources etc.

The just savings principle follows from the principle of intergenerational moral impartiality (see below).

Priorities

The principles are ordered in lexical priority as follows:

1) The liberty principle: The basic liberties of citizens are, roughly speaking, political liberty (i.e., to vote and run for office); freedom of speech and assembly, liberty of conscience, freedom of property; and freedom from arbitrary arrest. It is a matter of some debate whether freedom of contract can be inferred as being included among these basic liberties.

The liberty principle protects the individual’s civil and political rights.

2) The arrangement of social and economic inequalities:

a) The principle of fair equality of opportunity requires not merely that offices and positions are distributed on the basis of merit, but that all have reasonable opportunity to acquire the skills on the basis of which merit is assessed.

b) The difference principle strives for the greatest benefit to the least-advantaged members of society.

Theory of Justice, Wikipedia

Liberty and human rights

By assigning lexical priority to human rights they become a side constraint for every theory that seeks a quantitative optimization of the state of affairs. Rights theorists demand that (1) and (2a) conform to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. John Rawls focused on the avoidance of totalitarian regimes and the protection of minorities.

The unprincipled proliferation of human right claims in international documents (e.g. the right to periodic holidays with pay, stated in article 24 of the Universal Declaration) explains why Rawls began to pursue more austere approaches (Human Rights and Duties of Assistance, Aachen University).

Human rights balance the right to liberty (of the strong) with the right to protection (of the weak). Liberties are therefore connected to duties (see rights-duty duality). The Declaration of Human Duties and Responsibilities (DHDR) transforms human rights into a legal system.

Liberty and redistribution

A social contract based on the liberty principle is compatible with capitalism and produces social and economic inequalities. Bernard Mandeville, an 18th century political economist and satirist, postulated in his Fable of the Bees that vicious greed leads to invisible cooperation if properly channeled. The idea was taken up by Adam Smith, who claimed that, in capitalism, egoistic behavior promotes the good of the community through a principle that he called “the invisible hand”. Experience has shown however that the “invisible hand” cannot protect many people from starving and that free markets have to be complemented by redistribution.

The essence of Rawls’ understanding of liberty can be found in the Preamble of the Federal Constitution of the Swiss Federation:

“…only those who use their freedom remain free, and the strength of a people is measured by the welfare of its weakest members;

Fair equality of opportunity

Rawls’ concept of equality of opportunity goes beyond the one of classical utilitarianism. He denies an over-representation of upper class members in offices and positions even if it produces an increase in total welfare. The equal formal access to offices and positions is not sufficient; the statistical probability for lower class members to succeed has to be the same as for upper class members. For an example see [Clarenbach, chapt.3.2]

The difference principle

The difference principle holds that differences in wealth, status, etc. can be defended only if they create a system of market forces and capital accumulation whose productivity makes the lowliest members of society better off than they would be under a more egalitarian system. The difference principle is the safest principle (Justice as Fairness, by Charles D.Kay) and corresponds to a risk-averse strategy (Rawls Unrisky Business, by Jim Holt). Its implementation though is far from trivial:

1. Maximin interpretation:

If agents (A, B) can have incomes (5, 6) or (4, 9) then the former distribution must be chosen.

Maximin encounters the following problem: If agents (A, B, C) can have incomes (5, 6, 9) or (5, 7, 8), then Maximin is indifferent. Maximin encounters the following problem:

If the worst-off life has higher welfare in one population as compared to another one, then the former population is always better and the differences in the welfare of the other lives do not matter at all. The slightest gain in welfare for one person outweighs a very large loss for any number of people (Arrhenius, 101). This consequence is called dictatorship of the worst-off.

2. Leximin interpretation (not to be confused with the lexical priority of human rights):

If agents (A, B, C) can have incomes (5, 6, 9) or (5, 7, 8) then the latter distribution must be chosen. The second worst-off decides. If B’s income is the same in both distributions, then C’s income decides etc.

Leximin implies the dictatorship of the worst-off, as well as Maximin: If agent A’s income is minimally higher in the second distribution and the income of B and C considerably lower, then the first distribution must be chosen.

3. Prioritarian interpretation: Let’s return to Rawl’s definition of the difference principle: “Social and economic inequalities are to be arranged so that they are (…) to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged (…)”. The term greatest can be interpreted in such a way that everybody profits from inequalities, but that the least advantaged profit most. A prioritarian rule would e.g. distribute savings in such a way that the quota increases with decreasing welfare. Conversely the taxes owed would increase with increasing welfare.

Intergenerational moral impartiality

For the definition of moral impartiality see Impartiality, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

According to Rawls it is unjust to let the actual generation with its temporary and biased interests decide about the fate of future generations. The principle of impartiality should not only govern the distributive justice within the actual generation, but also among different generations.

- The principle says that the actual generation is not allowed to improve its situation at the cost of future generations.

- Inversely it says that the actual generation cannot be obliged to make more sacrifices than future generations

According to Rawls the principle of intergenerational moral impartiality follows from the idea of the original position.

But the distribution of economic welfare among generations is the subject of a controversial discussion; see e.g.[Broome 2008].

Comparison with the Charter of the United Nations

Rawls’ theory is a concept for domestic justice, but it shares key values with the Charter of the United Nations:

1. The UN Charter promotes peace and security. Rawls' theory does it indirectly by establishing a just and stable society. Within the framework of a fair social contract, he advocates the monopoly of violence of the state.

2. Rawls' theory and the UN Charter protect and promote basic liberties. They emphasize the rights to freedom of thought, expression, association, and participation in political and social life. The UN Charter, through its Universal Declaration of Human Rights and subsequent conventions, additionally upholds economic, social, and cultural rights.

3. Rawls' theory emphasizes the importance of equal opportunities, regardless of race, ethnicity, or gender. The UN Charter prohibits discrimination based on race, color, sex, language, and religion.

4. Rawls' theory promotes solidarity by the difference principle. The UN Charter fosters solidarity by the Sustainable Development Goals and by assisting countries affected by natural disasters, conflicts, and other emergencies.

These common values also increase the chances that domestic justice can be improved in non-democratic societies. The Human Rights Council has the mandate to "contribute, through dialogue and cooperation, towards the prevention of human rights violations and respond promptly to human rights emergencies". In 2005 a global consensus on justified violence has been reached under the title “Responsibility to Protect”. It concerns the prevention of genocide, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and ethnic cleansing:

The responsibility to protect is a norm or set of principles based on the idea that sovereignty is not a privilege, but a responsibility (…). If a State is manifestly failing to protect its citizens from mass atrocities and peaceful measures are not working, the international community has the responsibility to intervene at first diplomatically, then more coercively, and as a last resort, with military force (…). The authority to employ the last resort and intervene militarily rests solely with United Nations Security Council and the General Assembly (Responsibility to Protect, Wikipedia).

For more information on the UNO’s mission for human rights, peace and security see Negative Utilitarian Priorities.

2.4 Comparison with Classical Utilitarianism

Utility

1. In Bentham’s and Pigou’s utilitarianism the term utility corresponds to the happiness which is created by consumption. In the course of history the concept of utility became more abstract and was finally interpreted as the dominant end of human behavior (no matter what that is).

2. The replacement of the abstract concept of utility by the concrete meaning happiness is called hedonic reduction. Hedonic reduction opens the theory to empirical testing [Hirata, 24]. Examples:

- Quality of life (sociology)

- Well-being (psychology)

- Welfare (economics)

- Life satisfaction (happiness economics)

- Quality-adjusted life year (health care)

3. The application of game theory – as well as the utilitarian welfare functions – presupposes that utility can be measured on a cardinal scale and that it is amenable to an interpersonal comparison see [Clarenbach].

Game theory

Indifference curves are a means to compare concepts of distribution but we lack a rational criterion to select a specific distribution out of the many possible ones. Game theory is a possible means to find such a criterion. An impartial observer in the original position considers inequality as a risk, which has to be properly weighted in order to attain the best state of affairs.

The classic expositions of Harsanyi and Rawls produce a synthesis that is consistent with the modern theory of non-cooperative games, see [Binmore]. From a game theoretical view Harsanyi’ utilitarianism is compatible with the difference principle according to Rawls. The (risk-neutral) Bayesian maximization of utility converges towards Rawls’ (risk-averse) Maximin principle, if the weight of the worst cases increases.

Consequentialism

Historically, hedonistic utilitarianism is the paradigmatic example of a consequentialist moral theory. This form of utilitarianism holds that what matters is the aggregate happiness, i.e. the happiness of everyone and not the happiness of any particular person (Consequentialism, Wikipedia)

Why should we subscribe to consequentialism?

An argument for consequentialism is contractarian. Harsanyi argues that all informed, rational people whose impartiality is ensured because they do not know their place in society would favor a kind of consequentialism. Broome [1991] elaborates and extends Harsanyi's argument (Consequentialism, Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

This argument is disputed (see the discussion of the liberty principle below). For those who approve the argument, however, the common denominator of Harsanyi’s utilitarianism and Rawls’ Theory of Justice is contractarian. At the same time Harsanyi’s approach leads to a justification of classical utilitarianism from a remarkably new point of view. In the following we compare Rawls’ difference principle with the major competing theory of Harsanyi:

Harsanyi’s equiprobability model

Harsanyi’s equiprobability model (Gleichwahrscheinlichkeitsmodell) uses the following definition of impartial decisions:

- The impartial observer is an individual within society.

- After every decision influencing or changing society this individual can find himself with equal probability in every possible position in the changed society.

- Risk is defined as a product of utility and (mathematical) probability. The expected value of a decision is calculated by adding all possible risks.

Harsanyi’s concept (similarly to Rawls’) converts normative statements about solidarity into normative statements about risk. Harsanyi rejects Rawls risk-averse strategy, claiming that it is irrational to make behaviour dependent on some highly unlikely unfavourable contingency regardless of its low probability [Harsanyi, 1975]. He recommends not to base decisions on the worst case but on the Bayesian maximization of utility. Rawls in contrast is convinced that the rational choice of an individual behind the veil of ignorance is the Maximin strategy [Gaus].

The priority of the liberty principle (1)

The two assumptions of classical utilitarianism

1. individuals having similar utility functions

2. diminishing marginal utility

can be interpreted as moral and political principles in a somewhat technical language (rather than psychological propositions).

One might say that this is what Bentham and others really meant by them, at least as shown by how they were used in arguments for social reform (…). But this still leave the mistaken notion that the satisfaction of desire has value in itself (…). To see the error of this idea one must give up the conception of justice as an executive decision altogether and refer to the notion of justice as fairness. Participants in the social contract have an original and equal liberty and their common practices are considered unjust unless they accord with principles which the contractors freely acknowledge before one another and so accept as fair [Rawls 1958, 191-192].

Justice cannot be the result of an executive decision which maximizes the total utility of the society; it must be a consensus of contractors with regard to liberty and solidarity. This consensus or compromise is an example of a reflective equilibrium.

The priority of the liberty principle (2)

John Stuart Mill’s utilitarian arguments for the priority of liberty rights are the following:

- Without liberty the individuals cannot articulate their preferences and the society lacks diversity. Without diversity there is no maximization of utility.

- A constitution which is based on liberty rights guarantees legal security. The fear of arbitrariness, torture etc. causes an enormous loss of utility.

The goods that are associated with the term liberty have a corresponding high weight within the utility function. But, from a utilitarian point of view, despite of this high weight, there is still a trade-off with other goods.

Examples:

1. A minor worsening of liberty rights would probably be tolerated for a huge gain in economic welfare. In reality the political debates prove that liberty rights don’t have an absolute priority. In the trade-off between liberty rights and economic welfare repressive regimes often find support in the population.

2. A medic cares for two critically ill patients, one of them suffers more and has no chance to survive, whereas the other suffers less and is curable. The medic has only one dosage of the required medicament. Rawls would probably give the medicament to the deadly ill because he/she suffers more, a utilitarian would give it to the one with the higher potential to survive. The utilitarian position has a good chance to be accepted by the majority.

[Clarenbach, chapt.3.3]

Rawls’ liberty principle has lexical priority and doesn’t allow any trade-off [Rawls 1958, 184-187].

While Mill recognized that reasons for justice have a special weight, he thought that it could be accounted for by the special urgency of the moral feelings which naturally support principles of such high utility. But it is a mistake to resort to the urgency of feeling; as with the appeal to intuition, it manifests a failure to pursue the question far enough [Rawls 1958, 189].

Example:

The conception of justice as fairness, when applied to the practice of slavery would not allow one to consider the advantages of the slaveholder (…). The gains accruing to the slaveholder cannot be counted as in any way mitigating the injustice of the practice [Rawls 1958, 188].

Classical utilitarianism in general (not only Mill’s utilitarianism) lacks a principle for the protection of the individual.

The example shows that in Rawls’ theory – when liberty is at stake – the means are more important than the end. In contrast to utilitarianism he supports the process-view of justice and not the end-state view (or outcome-view).

The priority of the liberty principle (3)

Harsanyi’s concept is not restricted to the economic aspect of welfare (the difference principle). He assumes that, despite of the high weight the liberty principle has within the utility function, there is still a trade-off with other goods. Rawls however, insists on the absolute priority of the liberty principle. Classical utilitarianism can only be reconciled with the concept of fairness, if fairness is considered to be a side constraint of the utility function. But then utilitarianism loses its characteristics:

If one wants to continue using the concepts of classical utilitarianism, at least the utility functions must be so defined that no value is given to the satisfaction of interests which violated the principles of justice. In this way it is no doubt possible to include these principles within the form of the utilitarian conception; but to do so is, of course, to change its inspiration altogether as a moral conception. For it is to incorporate within it principles which cannot be understood on the basis of a higher order executive decision aiming at the greatest satisfaction of desire [Rawls 1958, 191].

Example:

Retributive justice can be implemented within a social contract of the Rawls’ type, but has no priority in the maximization of welfare. Retributive justice postulates that there should be a proportion between doing well and faring well. Not only is the result important but also the means that produced the result:

- Relative justice: A world where thugs fare better than decent people is morally objectionably, even if the total of the decent people’s welfare is not affected [Temkin, 354].

- Absolute justice: A world where thugs fare well is morally objectionable, even if decent people fare better than thugs [Temkin, 357]

The second principle of justice

The second principle excludes the justification of inequalities on the grounds that the disadvantages of those in one position are outweighed by the greater advantages of those in another position. This rather simple restriction is the main modification I wish to make in the utilitarian principle as usually understood (…). It is a restriction of consequence, and one which utilitarians, e.g. Hume and Mill, have used in their discussions of justice without realizing apparently its significance [Rawls 1958, 168]

Animal welfare

A major point of criticism in Rawls’ concept is the lacking protection of animals. The impartial observer should protect all sentient beings according to their degree of suffering, no matter if they think rational and no matter if they are able to sign a contract. Such an impartial observer, though, would transcend the boundaries of social contract theory.

Bentham is widely recognized as one of the earliest proponents of animal rights. He argued that animal pain is very similar to human pain and that the day may come when the rest of the animal creation may acquire those rights which never could have been withholden from them but by the hand of tyranny. Bentham argued that the ability to suffer, not the ability to reason, must be the benchmark of how we treat other beings. If the ability to reason were the criterion, many human beings, including babies and disabled people, would also have to be treated as though they were things (Jeremy Bentham, Wikipedia)

Rawls was conscious that his concept doesn’t include all aspects of ethics:

Justice as fairness is not a complete contract theory. For it is clear that the contractarian idea can be extended to the choice of more or less an entire ethical system, that is, to a system including principles for all the virtues and not only for justice (…) Obviously if justice as fairness succeeds reasonably well, a next step would be to study the more general view suggested by the name "rightness as fairness." But even this wider theory fails to embrace all moral relationships, since it would seem to include only our relations with other persons and to leave out of account how we are to conduct ourselves toward animals and the rest of nature. I do not contend that the contract notion offers a way to approach these questions which are certainly of the first importance; and I shall have to put them aside [Rawls 1958].

We must recognize the limited scope of justice as fairness.

3. Negative Utilitarianism (NU)

Ancient world

The idea to formulate an ethical goal negatively originates in Buddhism and is more than 2500 years old. The teachings of Buddha may have influenced the Greek philosopher Epicurus, who founded his famous Garden in Athens 307 BC (see Indian Sources of Hellenistic Ethics).

While Epicurus has been commonly misunderstood to advocate the rampant pursuit of pleasure, what he was really after was the absence of pain (both physical and mental, i.e., suffering) - a state of satiation and tranquility that was free of the fear of death and the retribution of the gods. There is a state of perfect mental peace (ataraxia) where we do not suffer pain, and where we are no longer in need of pleasure (Epicurus, Wikipedia).

Early utilitarianism

Historically utilitarianism was inspired by Stoicism and Epicureanism and therefore closer to negative utilitarianism than the contemporary interpretation:

Although the favored means of the term negative welfarism – a stoician-like control of the birth of one’s desires which it also calls “liberation” (moksa) – is in a sense opposed to economists’ conception, scholarly welfarism is in fact historically the direct descent of this Indian philosophy. Indeed, the 18th century founders of utilitarianism were thoroughly inspired by Stoicism and Epicureanism, whereas the influence of Buddhist and Jain thoughts on Stoician and other Hellenistic philosophies is explained in the previous reference. The oblivion of self-formation occurred with that of the Rousseau-Kant “autonomy” by some narrowminded post-Mill 19th century scholars. Even Mill’s “choice of lifestyle” is a downgrading of full eudemonistic self-formation (Macrojustice from Equal Liberty, Serge-Christoph Kolm).

Also, the Stoic cosmopolitanism corresponds well to utilitarianism. Stoicism, in contrast to Buddhism, was characterized by an optimistic world view.

In contemporary negative utilitarianism we find both, optimistic and pessimistic visions of the future; see Antinatalism and the Minimization of Suffering.

Popper

In the 20th century, the idea to formulate an ethical goal negatively is attributed to Karl Popper:

…there are no institutional means of making a man happy, but a claim not to be made unhappy, where it can be avoided. The piecemeal engineer will, accordingly, adopt the method of searching for, and fighting against, the greatest and most urgent evils of society, rather than searching for, and fighting for, its greatest ultimate good [Popper 1945/1966, 158]

At this point of chapter 9, Popper added his controversial note 2:

I believe that there is, from the ethical point of view, no symmetry between suffering and happiness, or between pain and pleasure. Both the greatest happiness principle of the Utilitarians and Kant’s principle “Promote other people’s happiness…” seem to me (at least in their formulations) wrong on this point which, however, is not completely decidable by rational argument (…). In my opinion human suffering makes a direct moral appeal, namely, the appeal for help, while there is no similar call to increase the happiness of a man who is doing well anyway.

A further criticism of the Utilitarian formula “Maximize pleasure” is that it assumes, in principle, a continuous pleasure-pain scale which allows us to treat degrees of pain as negative degrees of pleasure. But, from the moral point of view, pain cannot be outweighed by pleasure and especially not one man’s pain by another man’s pleasure. Instead of the greatest happiness for the greatest number, one should demand, more modestly, the least amount of avoidable suffering for all; and further, that unavoidable suffering – such as hunger in times of unavoidable shortage of food – should be distributed as equally as possible.

There is some analogy between this view of ethics and the view of scientific methodology which I have advocated in my The Logic of Scientific Discovery. It adds to clarity in the fields of ethics, if we formulate our demands negatively, i.e. if we demand the elimination of suffering rather than the promotion of happiness. Similarly, it is helpful to formulate the task of scientific method as the elimination of false theories (from the various theories tentatively preferred) rather than the attainment of established truths [Popper 1945/1966, 284].

Popper’s ethics was not only influenced by his epistemological work, but also by personal and historical experiences:

- The failure of happiness-promoting philosophies like classical utilitarianism and Marxism

- Sixteen of Popper’s closest relatives became victims of Nazi Germany, partially in Auschwitz, some committed suicide

Popper was not a utilitarian and did not use the term negative utilitarianism. His notes on ethics don’t represent a theory; they rather encourage a family of ethical concepts [Fricke, 13]. Furthermore, the context of his notes was the fight against the greatest and most urgent evils of society. The statement “From the moral point of view, pain cannot be outweighed by pleasure, and especially not one man’s pain by another man’s pleasure” does not claim that pleasure has no value. If we consider the context it means that – from the moral point of view – the pain of an Auschwitz victim cannot be outweighed by later pleasure, especially not by another man’s pleasure. Applying Popper’s statement to the case of a pinprick [Pearce] is a blatant misinterpretation of his intentions. Another misinterpretation is known under the term World Destruction Argument [Knutsson]. It stems from R.N.Smart:

R.N.Smart

The term negative utilitarianism was introduced by R.N.Smart in a paper criticizing Popper’s approach to ethics:

….one may reply to negative utilitarianism (hereafter called NU for short) with the following example, which is admittedly fanciful, though unfortunately much less so than it might have seemed in earlier times.

Suppose that a ruler controls a weapon capable of instantly and painlessly destroying the human race. Now it is empirically certain that there would be some suffering before all those alive on any proposed destruction day were to die in the natural course of events. Consequently, the use of the weapon is bound to diminish suffering, and would be the ruler’s duty on NU grounds (…).

Admittedly my example does not quite work as it stands against Professor Popper inasmuch as he propounds two other principles to set alongside NU, viz. (briefly) "Tolerate the tolerant" and "No tyranny". Presumably the benevolent world-exploder might be thought intolerant and/or tyrannical (…) …if we allow "Tolerate the tolerant" and "No tyranny" to stand as principles alongside NU, there will be a conflict between them and NU regarding our example. If we take NU seriously, surely we should over-ride the other principles [Smart 1958].

Popper maintained indeed that suffering has unique moral urgency and importance, but – true to his anti-totalitarian attitude – he did not postulate that the minimization of suffering should override the other two principles.

Summary Definition

Negative utilitarianism (NU) is an umbrella term for all types of utilitarianism which model the asymmetry between suffering and happiness [Fricke, 14]. It variously includes versions that

1. assign a relative priority to the avoidance of suffering

2. assign an absolute priority to the avoidance of suffering

3. consider non-existence to be the best possible state of affairs

R.N.Smart’s definition

We use the abbreviation NU as an umbrella term in this paper, but sometimes it refers to the historically first version, as defined by [Smart 1958]. R.N.Smart’s version has the following characteristics:

- It is hedonistic (as opposed to preference-based versions).

- It completely denies the moral value of happiness [Pearce] and therefore corresponds to the third of above concepts.

However, it turned out that R.N.Smart misinterpreted Karl Popper’s notes on ethics.

Popper’s definition

Popper later clarified that his notes on ethics were only meant for public policy:

I also suggested that the reduction of avoidable misery belongs to the agenda of public policy (which does not mean that any question of public policy is to be decided by a calculus of minimizing misery) while the maximization of one’s happiness is to be left to one’s private endeavour. (I quite agree with those critics of mine who have shown that if used as a criterion, the minimum misery principle would have absurd consequences) [Popper, Volume II, Addenda 13, 438]

|

Popper’s ethics minimizes suffering at the aggregate level, under consideration of two other principles: 1. Tolerate the tolerant 2. No tyranny

|

In the following we adopt Popper’s concept in two steps:

1. The minimization of suffering at the aggregate level, which is the utilitarian part of Popper’s ethics (chapter 3.3).

2. The conflict between the minimization of suffering and human rights, where human rights stand for Popper’s principles “tolerate the tolerant” and “no tyranny”. Human rights establish, among others, a similarity between Popper's concept and Rawls' theory of justice (chapter 3.4).

Minimization of suffering at the aggregate level

The first task is to establish a metric for measuring ethical progress. For that purpose we must clarify the relation between the different levels of happiness and suffering. If the metric is defined at the aggregate level then

- there is an ethical norm for compensations of happiness and suffering across different persons (inter-personal compensations)

- but no corresponding norm for compensations within the same person (intra-personal compensations).

Versions of NU which set norms for intra-personal compensations/trade-offs are the Absolute NU, Lexical (threshold) NU, and Weak NU. For information on these versions see Why I’m Not a Negative Utilitarian.

Since we discard utility functions at the individual level

- individual welfare is assessed by means of surveys on subjective life satisfaction (as in happiness economics)

- and not by means of calculations as in the Weak NU and neoclassical economics [Hirata, 26].

Under these premises

- the term happiness is a synonym for life-satisfaction and positive welfare.

- the term suffering stands for uncompensated suffering [Fricke, 18] and is a synonym for negative welfare.

Following the versions in the summary definition, described on the aggregate level:

1. Relative priority – Moderate NU

A relative priority of (the avoidance of) suffering means that happiness has moral value, but less than suffering. The moral weight of suffering can be increased by using a “compassionate” metric, so that the result is the same as in prioritarianism. The ethical priority increases with the level of suffering. If the balance between suffering and happiness turns negative, then the maximization of happiness turns into a minimization of suffering (see chapter 3.3).

2. Absolute priority – Strict NU

According to strict negative utilitarianism the value of a population is calculated by summing the welfare of all lives with negative welfare in the population. Lives with positive welfare neither add to nor detract from the value of a population [Caviola, 5-6, 19] [Arrhenius, 100].

We will discard absolute priority in this paper, because it represents a border case of relative priority, where the moral weight of happiness converges towards zero. Absolute priority can be approximated by relative priority. Relative priority is the general model.

Note that the strict NU considers an empty population as the lesser evil, and not as the best possible state. Lives with positive welfare don’t count, but they exist. If suffering could be eradicated one day (e.g. by transhumanism), then the promotion of happiness becomes mandatory (Lexical NU), supererogatory or morally neutral [Fricke 14, 18].

3. Non-existence as best possible state – Negative preference utilitarianism

In this axiology there are no lives with positive welfare. We will discard it in this paper. Without metaphysical assumptions the statement that “no state of affairs can be better than non-existence” is counter-intuitive for most people; see Negative Preference Utilitarianism.

For the reasons given above we will focus on the moderate NU.

Definition

The moderate NU is a metric within modern hedonistic utilitarianism, which assigns a higher weight to the avoidance of suffering than to the promotion of happiness. The moral weight of suffering can be increased by using a "compassionate” metric, so that the result is the same as in prioritarianism (This corresponds to one of the definitions of NU in Utilitarianism, Wikipedia). In contrast to the Weak NU, the moderate NU is only concerned with the inter-personal compensation of suffering by happiness.

The term moderate means that happiness is not completely devaluated:

- classical utilitarianism weighs happiness and suffering identically

- strict negative utilitarianism only weighs suffering

The moderate NU lies somewhere in between, i.e. it takes into account both happiness and suffering, but weighs suffering more than happiness. The ethical priority increases with the level of suffering (as in prioritarianism).

Semantics

- The term utility refers to life satisfaction or wellbeing-adjusted life years (in analogy to qalys) and not merely to pleasure. The data come from surveys and focus groups [Broome 2004, 261]. A synonym for life satisfaction is evaluative happiness. An evaluation is more than the description of an affect; it implies a judgment [World Happiness Report 2012, 6, 11].

- The term modern utilitarianism is associated with the work of John Broome in this paper [Broome 1998].

- The term hedonistic is used to delimit the theory from preference utilitarianism [Broome 1996].

- The hedonic scale contains negative values [Broome 2004, 213].

For a comparison of Broome’s utilitarianism with prioritarianism see Antinatalism and the Minimization of Suffering.

Against negative utilitarianism

Refutations of NU [Gustafsson] only work

- for versions of NU which override compensation (of suffering by happiness) within the same person (like Absolute NU, Lexical NU and Weak NU)

- but not for versions which make compensation more difficult across different persons (like the moderate NU and the Weak Lifetime NU).

For more information about this topic see Why I’m (Not) a Negative Utilitarian – A Review.

In order to refute the moderate NU, one has to refute prioritarianism. This raises the question: If the two theories are functionally equivalent, why don’t we just use prioritarianism? In practice it makes no difference indeed. But in theory – according to John Broome – prioritarianism is obsolete, and not utilitarianism, see Antinatalism and the Minimization of Suffering.

The metric of the hedonic scale

Classical utilitarianism assumes that suffering and happiness have equal weight. Current surveys on subjective life satisfaction express this “equal weight” by linear and symmetric point scales. Let us assume there was a survey asking the question:

How satisfied are you with your life as a whole: Very happy, happy, neutral, suffering, severely suffering?

Classical utilitarianism transforms these ordinal values into cardinal values as follows:

Table 1

Transformation into cardinal values

|

Ordinal |

Cardinal |

|

very happy |

+2 |

|

happy |

+1 |

|

neutral |

0 |

|

suffering |

-1 |

|

severely suffering |

-2 |

The moderate NU suggests that the hedonic scale is asymmetric. This thesis is justified by intuitions like the following:

- We should realize that from the moral point of view suffering and happiness must not be treated as symmetrical; that is to say, the promotion of happiness is in any case much less urgent than the rendering of help to those who suffer, and the attempt to prevent suffering [Popper 1945/2003, Volume I, Notes to Chapter 5, Note 6]

- It is more important to relieve suffering than to increase (already happy people’s) happiness. We can retain this important intuition … by giving more weight to negative welfare than to positive welfare [Arrhenius, 138]

Furthermore, the moderate NU suggests that the hedonic scale is nonlinear (Fig.2). This thesis is justified by the following intuition:

The moral value of an increase in welfare matters more, the worse off people are [Broome 2004, 224] [Lumer, 6] [Arrhenius, 110].

Fig.2

- If the majority of the participants of a survey report a positive welfare, then the total is necessarily positive in classical utilitarianism. The suffering of a minority can easily be compensated by the happiness of the majority.

- In the moderate NU the total may turn negative, because of the higher moral weight of negative welfare. If total welfare turns negative, then we should rethink population ethics; see Antinatalism and the Minimization of Suffering.

Conclusion:

- In classical utilitarianism the promotion of happiness has the same ethical priority as the avoidance of suffering, as long as the contribution to total welfare is the same.

- In negative utilitarianism the promotion of happiness has less (or even no) priority as compared to the avoidance of suffering.

If ethical priorities are expressed by the metric of the hedonic scale [Broome 1991, 222] then the metric of the two axiologies is necessarily different.

Negative total welfare

If the moderate NU is “only a metric” within hedonistic utilitarianism: What is the reason for using a special term for this metric?

The reason is that classical utilitarianism is associated with positive totals (Fig.1):

▪ In classical utilitarianism the hedonic scale is linear and symmetric. The theory does not exclude negative totals, but in practice most utilitarians assume that – given the current state of affairs – total welfare is positive.

▪ In the moderate NU the hedonic scale is non-linear and asymmetric. The theory does not exclude positive totals, but the current state of affairs is considered to be negative. The intuition that “global suffering cannot be compensated by happiness” turns global welfare negative, so that the maximization of happiness turns into a minimization of suffering.

Fig.1

The moral weight of suffering

Rationality

Intuitions with regard to global welfare are controversial:

- The majority thinks that seven billion happy people can easily outweigh the extreme suffering of a minority (Fig.1 metric 1). Surveys like the OECD Better Life Index, Satisfaction with Life Index, and the World Happiness Report suggest that there is persistent happiness on earth.

- Buddhists, Gnostics, Schopenhauer, Popper and antinatalists do not share this intuition (Fig.1 metric 2)

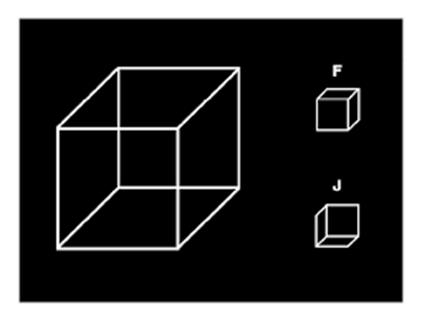

The majority considers the latter people to be highly risk-averse or even irrational, but possibly the majorities’ perception of risk is distorted. The majority and minority view are like two sides of a reversible picture:

Fig.3

Picture from the internet (author unknown)

In everyday life we see the suffering and death of others from a safe distance, like the information in a newspaper or on television. But this perception can change suddenly (just like the reversible picture in Fig.3) when family members, close friends or the observer him-/herself are struck by a horrible accident, illness or crime. In this moment we start to realize, that the everyday perception could be distorted.

- Analytical arguments for the rationality of a negative global welfare can be found in The Denial of the World from an Impartial View.

- Empirical arguments can be found in Is There a Predominance of Suffering?

Cost-benefit

Cost-benefit analysis is, amongst others, a tool of welfare economics to maximize utility. Take the Copenhagen Consensus as an example:

- The Copenhagen Consensus seeks to increase global welfare, where welfare is measured in terms of the GDP. It is assumed that general welfare correlates with economic welfare.

- The focus of negative utilitarianism is on the minority of the most suffering people. The term welfare is used in a general sense (life satisfaction) and not reduced to economic welfare.

From a negative utilitarian perspective an increase in the world’s GDP is (ethically) worthless if it does not reduce the worst kinds of suffering. The advantage of the GDP consists in being a measurable criterion. Humanitarian aid can comparatively easily be linked to an increase of the GDP, whereas the effect of peace and human rights activities are hard to calculate. The Copenhagen Consensus discards political in favor of economic priorities. The method dictates the result. For more information on this topic see Negative Utilitarian Priorities.

3.4 Comparison with Rawls’ Theory

Human rights and the higher purpose – Moral killing

The relation between human rights and negative utilitarianism is complex:

- Human rights are the result of historical experiences (in particular the Holocaust). They prevent some of the worst cases of suffering and insofar can be seen as a consequence the negative utilitarian goal.

- Then again negative utilitarianism contradicts human rights, because it has a totalitarian claim. From a theoretical point of view moral killing (even the eradication of humanity) is justified under certain circumstances [Smart 1973].

In the latter case, human rights are subordinated under a higher principle (the eradication of suffering). But note that this subordination concerns consequentialism in general [Larmore, 4] [Knutsson]:

- The capital punishment in the U.S. illustrates that the idea is not far-fetched (The U.S. constitution was influenced by classical utilitarianism).

- Human rights may be violated in a moral dilemma called the torture of the mad bomber (www.friesian.com/valley/dilemmas.htm).

- The arguments against moral killing in classical utilitarianism are only of empirical nature. A classical utilitarian surgeon could sacrifice an old patient (e.g. in the context of organ transplantation) in order to save the life of a young patient, if the result is a net gain in happiness, and if it were possible to do it secretly. There is even a moral obligation to eliminate lives with negative welfare, if it were possible to do it painlessly and secretly [Chao, 60-61].

- If total welfare in a population turns negative, then classical utilitarianism minimizes suffering, as well as negative utilitarianism. The discussion concerning the priority of the liberty principle in chapter 2.4 applies to positive and negative utilitarianism.

An attempt to solve the problem consists in switching to a preference-based ethics. In preference-based ethics the preferences of the individuals have to be respected, so that the arguments against painless killing are of theoretical and not only empirical nature [Fricke, 20][Chao, 57-59]. However, in a utilitarian preference-aggregation, the preferences of the majority overrule the ones of the individual and the majority could theoretically decide to exterminate a minority [Hare, 121-122]. Obviously, the minority problem is not only disturbing in tyranny and fascism, but also in preference utilitarianism. History justifies a deep skepticism opposite to ethical theories which promise improvements by restricting human rights. Adherents of negative utilitarianism, who recognize the totalitarian potential as a problem, consider human rights as a side constraint and not as a subordinated issue [Wolf, 278] [Nozick]. Such an anti-totalitarian, suffering-focused ethics corresponds to a political party or movement within a democratic system.

Human rights and the higher purpose – Birth control

Human rights protect subjective values and guarantee that the individual cannot be subordinated to a higher purpose of any kind. If the higher purpose is the extermination of suffering, however, then reproductive liberty – which is considered to be a human right – might make it impossible to ever reach this goal. Even in a perfectly fair political system, suffering could be immense. Negative utilitarianism can at least demonstrate that overpopulation has a “price” in terms of a disproportionate negative utility; see Antinatalism and the Minimization of Suffering. Rawls’ theory only asks for a just distribution of suffering between generations. The minority, who votes for birth control must accept population growth, because the majority accepts it.

Non-contractual cases

Philosophers, who treat morality as primarily contractual tend to discuss non-contractual cases briefly, casually and parenthetically, as though they were rather rare. The contractarian view is that those who fail to clock in as normal rational agents and make their contracts are just occasional exceptions, constituting one more minority group, but not a central concern of any society [Midgley]

In negative utilitarianism the ethical goal to minimize suffering is guided by empathy. As compared to social contract theory it seems to be built on emotions. But these emotions conform to the contractor’s self-interest in the following cases:

- Every human being passes through stages where he/she depends on others. The child spends many years acquiring the competence in speech and consciousness which is typical for humans. Old people, finally, lose step by step their mental capabilities, in particular by strokes and dementia (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease).

- The contractor’s own future descendants could be mentally retarded, insane, handicapped or become orphans, so that it is in the contractor’s interest to protect them by law.

The protection of non-contractual cases also gets support from recent discoveries in biology:

- Self-interest is strongly influenced by the biological utility function, see God’s Utility Function. The insight that the temporary and biased self-interests (the motives of self-realization) are in truth the ones of the biological utility function can lead to a feeling of being manipulated, to the consciousness of heteronomy and to solidarity with the victims of biological mechanisms.

- In negative utilitarianism non-contractual cases also include sentient animals; speciesism is denied. This is reminiscent of ancient concepts or reincarnation, although genes are reincarnated rather than souls. Hinduism assumes that there is no essential difference between human souls and animal souls. Contemporary science reveals that sentient animals have a surprising genetic similarity to humans. Example: Chimpanzees and humans have 99% of coding DNA sequences in common (Humanzee, Wikipedia).

Animal rights and the higher purpose

Animal rights conflict with both Rawls’ theory of justice and negative utilitarianism:

- Animal rights conflict with Rawls theory (human rights) if animals and humans compete for resources

- Animal rights conflict with negative utilitarianism in cases where a violation of animal rights could reduce the total amount of suffering.

Moral dilemmas can only be avoided by retreating from life like Buddhist monks. But not every problem in the context of animal rights is an ethical dilemma:

- Slaughterhouses are not part of a moral dilemma because a vegetarian human population could progress as well.

- Animal experiments are only part of a moral dilemma, if they cannot be replaced by other research methods.

The difference principle

The absolute priority of the worst case is a possible interpretation of the difference principle, but in Rawls’ theory the worst case refers to economic welfare, whereas in negative utilitarianism it refers to general welfare.

According to Rawls risk-aversion follows from the idea of the original position and justifies the difference principle. But it is hard to see why distributive justice should be risk-averse and human rights risk-tolerant. Rawls obviously considered human rights to be risk-averse – consistent with the difference principle. This is plausible insofar, as human rights prevent some of the worst cases of suffering, like the torturing of opposition members in authoritarian and totalitarian systems [Stover]. But it is implausible in other cases:

Example: If a certain speed limit causes 2% or 20% victims a year is irrelevant in Rawls’ theory, if it reflects the will of the majority. A moral principle which demands to lower the speed limit against the will of the majority is considered to be authoritarian. Let us consider some justifications of risk-tolerance in the context of speed limits:

- Suffering belongs to life. Risk belongs to progress.

This argument does not hold because life and progress develop despite a lower speed limit.

- A further restricting of liberty rights asks too much from the majority and induces counterproductive results.

This argument does not hold because there are many laws demanding more self-control than a lower speed limit.

- To tolerate certain kinds suffering increases the competitiveness of a culture.

This is probably the essence of the matter. Road traffic is just one example of a whole collection of cruel customs with winners and losers, customs which are tolerated by the majority. The injustice concerns those who become victims despite denying the custom.

Conclusion: In many areas of life Rawls’ liberty principle allows applying Harsanyi’s risk-neutral utility maximization [California Digital Library], although the concept of the original position argues for the rationality of risk-aversion.

|

We all have the strength to endure the misfortune of others

|

Intergenerational moral impartiality

We shall have to make a serious effort to predict our actions’ effects on population, and to assign a value to those effects. In many cases, the factor we typically ignore—population—is likely to turn out the most important of all [Broome 2005, 411].

The number of future persons exceeds by far the ones of the actual generation:

- Rawls’ theory is neutral with regard to expansion and contraction, as long as the principle of intergenerational moral impartiality is respected, i.e. as long as the changes do not disadvantage an actual or future generation.

- Negative utilitarianism considers population ethics as a means to minimize total negative welfare.

In negative utilitarianism the future generations (as far as they can be analyzed) are treated like components of a multi-generation entity. This multi-generation entity is subject to a risk-averse principle in much the same way as a single generation is subject to the (risk-averse) difference principle. The actual generation therefore can be morally obliged to make sacrifices according to the same logic as a wealthy single person can be obliged to accept a redistribution of welfare. Possibly a small sacrifice of the actual generation could improve the situation of countless future generations. In Rawls theory there is no higher purpose like the total welfare across all generations. The principle of intergenerational moral impartiality assigns the same rights to each generation.

Example: If it were known that (due to a natural disaster) the world can only nourish a billion people after the next five generations then the actual world population (of about 7 billion people) would have to be reduced dramatically. But how should the responsibility be distributed among the generations?

- The logic of impartiality would ask for the same proportional reduction in each generation. Each single generation is a minority within the multi-generation entity. The arguments in favor of such a minority are the same as the ones in favor of minorities within a single generation.

- Negative utilitarianism treats multi-generations like a single entity. It would burden an over-proportional responsibility to the actual generation, if this policy reduces the accumulated suffering across all generations in question.

Population ethics is only one of many areas, where this principle applies:

- If it were known that biotechnological research leads to the eradication of suffering, then the actual generation of negative utilitarians would have an over-proportional responsibility to invest in this research.

- Conversely, the actual generation of negative utilitarians has an over-proportional responsibility to control and question high-risk technology, as far as this technology affects countless future generations.

For more information about negative utilitarian population ethics see Antinatalism and the Minimization of Suffering.

Comparison with Popper’s principles

Popper outlined the following three ethical principles [Popper 1945/2003, Volume I, Notes to chapter 5, Note 6, 255-256]:

(1) Tolerance toward all, who are not intolerant and who do not propagate intolerance (…) This implies, especially, that the moral decisions of others should be treated with respect, as long as such decision do not conflict with the principle of tolerance.

(2) The recognition that all moral urgency has its basis in the urgency of suffering or pain. I suggest, for this reason to replace the utilitarian formula “Aim at the greatest amount of happiness for the greatest number” or briefly “Maximize happiness”, by the formula “The least amount of avoidable suffering for all” or briefly “Minimize suffering”. Such a simple formula can, I believe, be made one the fundamental principles (admittedly not the only one) of public policy. (The principle “Maximize happiness”, in contrast, seems to be apt to produce a benevolent dictatorship) ……

(3) The fight against tyranny, or in other words, the attempt to safeguard the other principles by the institutional means of legislation rather by the benevolence of a person’s power.

Rawls knew Popper’s normative claims [Rawls 1958, 174] and may have been influenced by Popper’s work. Following a comparison of Rawls’ principles (chapter 2.3) with the ones of Popper:

- Rawls’ liberty principle is the basis of an open society as defined by Popper. It is reminiscent of Popper’s tolerance principle; see (1) above.

- Rawls’ difference principle takes account of Popper’s notes on the asymmetry between suffering and happiness. It is reminiscent of Popper’s call to minimize suffering; see (2).

- Rawls’ principle of equal opportunity is reminiscent of Popper’s institutional means of legislation against tyranny; see (3)

Popper should rather be associated with Rawls than with negative utilitarianism.

The implementation of the moderate NU has two aspects:

1. The metric for measuring ethical progress.

2. The derivation of ethical priorities.

In the following we focus on the metric for measuring ethical progress. Ethical priorities are discussed in

- Negative Utilitarian Priorities (public policy level) and

- Philosophy as Therapy (individual level)

Popper seemed to endorse a general duty to reduce suffering [Popper 1945/1966, 158].

Subjective indices

- Examples of positive utilitarian indices are the OECD Better Life Index, Satisfaction with Life Index, and the World Happiness Report.

- Ron Anderson proposes a negative utilitarian index by reversing the Cantril Ladder scale [Anderson, 5-6]. But he interprets the Cantril Ladder as a linear point scale, i.e. he does not account for the asymmetry between happiness and suffering.

A negative utilitarian index must be non-linear (chapt.3.3, Fig.2). The asymmetry increases with the intensity of suffering, i.e. the higher the level of suffering, the more happiness is required to compensate it [Caviola, 17-22]. For information about the degree of the asymmetry see Is There a Predominance of Suffering?

Objective indices

Because subjective indices include unavoidable kinds of suffering (like illnesses, aging and death) a corresponding ranking of nations cannot be related to the ethical standard of these nations. Objective indices focus on avoidable kinds of suffering. The International Human Suffering Index [Camp] and Anderson’s Objective Suffering Index [Anderson, 7] rely on the statistic of the World Bank, UN and other readily available resources.

- Objective indices exclude natural disasters in order to limit the measure to preventable suffering [Anderson, 8].

- Objective indices account for factors that are closely related to the definition of underdevelopment [Anderson, 7]. The correlation with the Human Development Index [Anderson, 14] therefore doesn’t come as a surprise.

- Objective indices do not consider the increase of technological risks as investigated in The Cultural Evolution of Suffering.

Subjective versus objective

In Happiness Economics, subjective life evaluations are related to objective data by means of factor analysis [Oswald]. Whereas above objective indices are defined by experts, factor analysis lets the majority decide about the determinants of suffering. Subjective suffering (partly) accounts for the ambivalence of technology.

Ron Anderson assessed a moderately high correlation between his subjective and objective suffering index. It seems that in higher developed nations subjective suffering correlates less with objective suffering than in lower developed nations [Anderson, 11].

Moral killing

The most controversial strategy of NU is a violent reduction of the population-size in order to improve the state of affairs [Fricke, 18]. An extreme pursuit of this thought leads to the extermination of humanity or life as a whole [Smart 1973]:

- A negative utilitarian believes that, if it was possible to exterminate all life in the universe instantly and painlessly and permanently, it would be correct and ethically required that we do so in order to prevent any future cases of suffering

- A classical utilitarian might decide either way, depending on his estimation of the relative amounts of future suffering and happiness.

(Introduction to utilitarianism, utilitarian.org):

There is, however, an empirical argument against such a strategy: Planning a project for the violent reduction of the population-size (e.g. by sterilization, inducing a nuclear war, destructing the biosphere etc.) would provoke immense distress and classify the supporters of this project among the worst kinds of lunatics or terrorists. A violent extermination of mankind is not feasible in practice. The result of such an attempt would be an increase in suffering and therefore contradict the ethical goal of NU.

Empirical arguments against moral killing are not convincing under all circumstances, but similar deficiencies can be found in classical utilitarianism and prioritarianism [Knutsson]. Adherents of consequentialism, who recognize the totalitarian potential as a problem, consider human rights as a basic condition, and not as a subordinated issue; see the section about Human rights and the higher purpose in chapter 3.4

For information about the moral ideal of childlessness see Antinatalism and the Minimization of Suffering.

Acceptance

Whatever the future holds, negative utilitarian ethics will presumably still fail to resonate with the overwhelming majority of the population (…). So perhaps the most effective way for a negative utilitarian to promote his/her ethical values is not to proselytize under that label at all. Instead, the negative utilitarian may find it instrumentally rational to give weight overtly to the "positive" values of ordinary classical utilitarians, preference utilitarians/preference consequentialists, and the far wider community of (mostly) benevolent non-utilitarians who share an aversion to "unnecessary" suffering. The indirect approach to NU is likely to yield the greatest payoff. Only by our striving to promote "positive" goals as well, and campaigning for greater individual welfare, is the ethic of NU ever likely to be realized in practice [Pearce].

Acceptance can be improved, if the NU-index is proposed as additional information, and not as a replacement of established indices. The NU-index strengthens the awareness that the suffering minority pays – in a statistical sense – the price for the happiness of the majority.

Negative utilitarianism

Negative utilitarianism (NU) is an umbrella term for ethics which models the asymmetry between suffering and happiness [Fricke, 14]. It includes concepts that

- assign a relative priority to the avoidance of suffering

- assign an absolute priority to the avoidance of suffering

- consider non-existence to be the best possible state of affairs

In this paper we investigate compensation across different persons (inter-personal compensation). For compensation within the same person (intra-personal compensation) see Why I’m (Not) a Negative Utilitarian.

1) A relative priority of (the avoidance of) suffering means that happiness has moral value, but less than suffering. The moral weight of suffering can be increased by using a "compassionate" metric, so that the result is the same as in prioritarianism. The more weight is assigned to suffering, the more difficult it becomes to compensate suffering by happiness. The intuition that “global suffering cannot be compensated by happiness” turns global welfare negative, so that the maximization of happiness turns into a minimization of suffering. The rationality of this intuition is investigated in The Denial of the World from an Impartial View and Is There a Predominance of Suffering?

2) Absolute priority represents a border case of relative priority, where the moral weight of happiness converges towards zero. Absolute priority can be approximated by relative priority. Relative priority is the general model.

3) Without metaphysical assumptions the statement that no state of affairs can be better than non-existence is counter-intuitive for most people; see Negative Preference Utilitarianism.

Rawls’ theory versus negative utilitarianism

1) Priority of human rights:

a) In negative utilitarianism it is theoretically possible to override human rights, if it serves the minimization of negative total welfare.

b) In Rawls’ Theory of Justice it is impossible to override human rights, even if this principle causes the perpetuation of suffering.

2) Distribution of welfare among social classes:

Rawls’ difference principle accords well with the intentions of negative utilitarianism, if the term welfare is interpreted as life satisfaction.

3) Compensation among generations:

a) In negative utilitarianism a generation may be obliged to sacrifice themselves, if it serves the long-term reduction of suffering.

b) Rawls’ theory promotes the principle of intergenerational moral impartiality.

4) Non-contractual cases:

a) In negative utilitarianism the minimization of suffering includes all sentient beings.

b) Rawls’ theory lacks a principle for the protection of non-contractual cases.

1. Anderson Ron (2012), Human Suffering and Measures of Human Progress, Presentation for a RC55 Session of the International Sociological Association Forum in Buenos Aires, Argentina

2. Arrhenius Gustav (2000), Future Generations, A Challenge for Moral Theory, FD-Diss., Uppsala University, Dept. of Philosophy, Uppsala: University Printers

3. Bentham, J., Value of a Pain or Pleasure (1778), in: B. Parekh (ed.): Bentham´s Political Thought, London 1973

4. Binmore Ken (1994), Game Theory and Social Contract, MIT Press

5. Bleiker Roland (2002), Rawls and the Limits of Civil Disobedience, Social Alternatives, Vol.21, No.2, 37-40, Australia

6. Broome John (1991), Weighing Goods, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, Paperback version 1995

7. Broome John (1996), Can there be a preference-based utilitarianism? Cambridge University Press

8. Broome John (1998), Modern Utilitarianism, In The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics and the Law, edited by Peter Newman, Macmillan

9. Broome John (1999), Ethics out of Economics, Cambridge University Press, UK