Antinatalism and the Minimization of Suffering

B.Contestabile First version 2005 Last version 2023

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Basics

2.1 The Asymmetry between Happiness and Suffering

2.2 Compassion

2.3 Risk-Aversion

3. Antinatalism

3.1 Basics

3.2 Comparison with Ancient Indian Philosophy

3.3 Comparison with Person-Affecting Views

3.4 Criticism and Reply

4.1 Basics

4.2 Comparison with Utilitarianism

4.3 Criticism and Reply

5.1 Basics

5.2 Scenarios of the Future

6. Conclusion

Starting point

Classical utilitarianism has the deficiency, that it favors expansion at the cost of the quality of life, see Repugnant Conclusion. Unconditional expansionism is a characteristic of the utility function of biology (the maximal proliferation of genes). It not only leads to lives with minimal welfare, but also to lives with negative welfare. The ethical goal to minimize suffering – which does not favor this expansion – conflicts with biological forces.

Type of problem

Does the ethical goal to minimize suffering necessarily lead to antinatalism?

Result

- cases where an expansion of the population reduces suffering,

- cases where a contraction of the population increases suffering, and

- cases where antinatalism doesn’t affect total welfare at all.

These scenarios, however, are currently not relevant. The growth of the world population – which will continue until the second half of the 21st century – is likely to have more negative than positive effects on global suffering (see The Cultural Evolution of Suffering). Consequently, for adherents of suffering-focused ethics, there are good reasons to promote antinatalism.

Starting point

Classical utilitarianism has the deficiency, that it favors expansion at the cost of the quality of life, see Repugnant Conclusion. Unconditional expansionism is a characteristic of the utility function of biology (the maximal proliferation of genes). It not only leads to lives with minimal welfare, but also to lives with negative welfare. The ethical goal to minimize suffering – which does not favor this expansion – conflicts with biological forces.

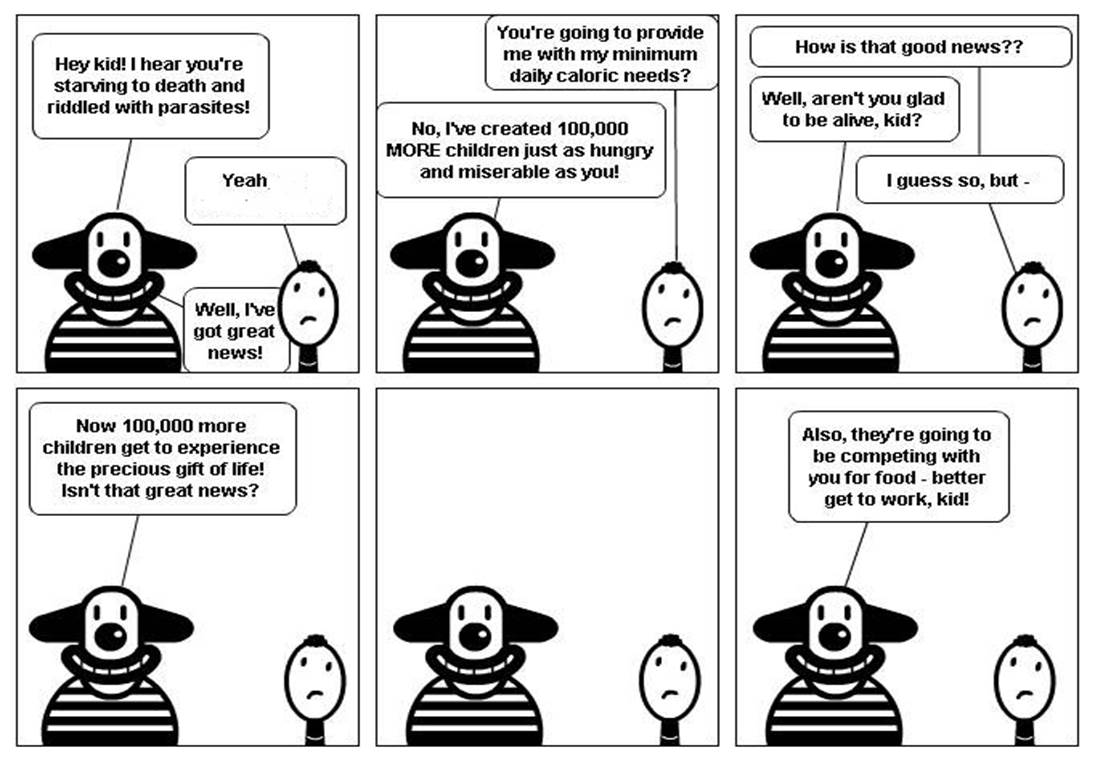

The following comic illustrates the conflict:

Robin Hanson, Curator, 9.Mar, 2011

Type of problem

Does the ethical goal to minimize suffering necessarily lead to antinatalism?

The ethical goal to minimize suffering is guided by compassion (chapter 2.2) and risk-aversion (chapter 2.3). As compared to social contract theory it seems to be built on emotions. But these emotions have a cognitive aspect. Compassion and risk-aversion

- reflect the asymmetry between suffering and happiness (chapter 2.1)

- are a rational answer to the fact that a significant part of our self exists in others (chapter 2.2)

From the perspective of Rawls’ Original Position compassion and risk-aversion are the same.

2.1 The Asymmetry between Happiness and Suffering

Physics

Life is subject to the laws of thermodynamics and destined to decay. Suffering is unavoidable because of aging, illness, and death. Happiness is avoidable; it can be terminated at any point in time.

Biology

- There are genetic defects which cause immense suffering (e.g. Sickle-cell disease). No corresponding phenomenon is known which causes immense happiness.

- There are more cases of chronic pain than cases of long-lasting pleasure.

- Due to evolutionary pressure, creatures are capable of experiencing more intense pain than pleasure. The pleasure of orgasm is less than the pain of deadly injury, since death is a much larger loss of reproductive success than a single sex act is a gain [Shulman].

- In Better Never to Have Been, the South African philosopher David Benatar argues that there are a number of “empirical asymmetries”. He demonstrates this through the thought experiment of asking us to imagine an offer of accepting a short duration of the very worst torture in order to experience a longer duration of the best pleasures imaginable. Most people, he claims, would intuitively turn down the offer. Pain is more negatively intense than pleasure is positively intense, in both kind and degree (On Antinatalism and Depression, Sam Woolfe).

Neurosciences

- Recent results from the neurosciences demonstrate that pleasure and pain are not two symmetrical poles of a single scale of experience but in fact two different types of experiences altogether, with dramatically different contributions to well-being. These differences between pleasure and pain and the general finding that “the bad is stronger than the good” have important implications for our treatment of nonhuman animals. In particular, whereas animal experimentation that causes suffering might be justified if it leads to the prevention of more suffering, it can never by justified merely by leading to increased levels of happiness [Shriver 2014.2].

- The experiences of pleasure and pain are mediated by different cognitive systems [Shriver 2014.1]. We have receptors for pain, but none in the same way for pleasure [Szasz 1957].

Psychology

- It is easy to make someone unhappy but much less easy to make that person happy again. It is easier to produce suffering than to produce happiness.

Bad is stronger than good, as a general principle across a broad range of psychological phenomena [Baumeister et.al.].

- A repetition of painful experiences leads to higher sensitivity, a repetition of pleasant experiences leads to lower sensitivity.

- There is a kind of suffering which causes irreversible damage to the psyche, i.e. the psyche cannot be repaired by a symmetrical kind of happiness.

- Given an initial level of happiness it is more likely to return to this level after a happy event (like marriage), than after an unhappy event (like divorce) [Diener 2006].

- Many believe that joy can be experienced only in contrast to suffering and misfortune and can only then be valued appropriately. But hardly anyone claims that first one has to feel real joy to at least know what suffering is [Stefan, 94].

- Let us consider increasingly negative events on one side and increasingly positive events on the other side. The psychological effect of the former increases at a faster rate compared to the psychological effect of the latter [Rozin & Rozyman] [Caviola, 17].

- For most humans the worst suffering, either experienced or imagined, is likely more intense than the best happiness. This may have neurobiological and evolutionary causes. Failing to avoid harmful actions could lead to death, whereas failing to avoid beneficial actions doesn’t have similarly bad consequences” [Caviola, 65].

- In valuing entire populations, the majority’s intuitions are asymmetric about happiness and suffering [Caviola, 5-8].

- Psychometrics confirms the asymmetric nature of the hedonic scale. Positive and negative affect carry different information and need to be separately measured and analysed [Diener 1984].

For more examples see Negativity Bias, Wikipedia.

Sociology

The following asymmetry in the acceptance of suffering and happiness seems to improve the survival value of the community:

- It is more difficult to take part in other people’s suffering than to take part in other people’s joy.

- A person who masters his/her grief gets more recognition than a person who remains controlled in the hour of triumph.

- Compassion and tears are considered to be a sign of weakness (unless the emotions express admiration for heroic people). Conversely happiness is interpreted as a sign of strength so that people don’t hesitate to show it.

[Smith, chapter 1, section 3].

Economics

- In welfare economics the idea of an asymmetry goes back as far as Arthur Cecil Pigou (1877-1959) and Hugh Dalton (1887-1962). The “law” of diminishing marginal utility and the logarithmic effect of absolute income on happiness (see Easterlin Paradox) may have their reason in the psychological asymmetry between suffering and happiness

- The expected utility theory generally accepts the assumption that individuals tend to be risk averse.

- In prospect theory, loss aversion refers to people’s tendency to strongly prefer avoiding losses to acquiring gains. Some studies suggest that losses are twice as powerful, psychologically, as gains (loss aversion, Wikipedia).

- A loss creates a greater feeling of pain compared to the joy created by an equivalent gain (Prospect Theory by James Chen).

Phenomenology

The best known description of an asymmetry between happiness and suffering is the First Noble Truth of Buddhism. In Western philosophy the Buddhist view was taken up by Schopenhauer. Following a contemporary statement in this philosophical tradition:

Physical embodiment, impermanence and transience prevent any permanent satisfaction of preferences. The phenomenology of suffering is not a simple mirrorimage of happiness, mainly because it involves a much higher urgency of change. In most forms of happiness this centrally relevant subjective quality which I have termed the “urgency of change” is absent, because they do not include any strong preference for being even more happy. In fact, a lot of what we describe as “happiness” may turn out to be a relief from the urgency of change. The subjective sense of urgency, in combination with the phenomenal quality of losing control and coherence of the phenomenal self, is what makes conscious suffering a very distinct class of states, not just the negative version of happiness. This subjective quality of urgency is also reflected in our widespread moral intuition that, in an ethical sense, it is much more urgent to help a suffering person than to make a happy person even happier [Metzinger 2017, 254-255].

Ethical priorities

The normative claim that an increase of welfare is more deserving at low levels of welfare than at high levels first appeared under the name “the priority view” in Derek Parfit’s renowned 1991 article “Equality or Priority.” But the idea dates back to Temkin’s 1983 Ph.D. thesis, where it was presented under the name “extended humanitarianism.” (Larry Temkin, Wikipedia).

The same concept can also be found in [Broome 2004, 224] [Lumer, 6] [Holtug, 13] [Mayerfeld] [Chauvier] and many others. Following some citations:

- We should realize that from the moral point of view suffering and happiness must not be treated as symmetrical; that is to say, the promotion of happiness is in any case much less urgent than the rendering of help to those who suffer, and the attempt to prevent suffering [Popper, 235, note 6(2) ].

- I believe that there is, from the ethical point of view, no symmetry between suffering and happiness (…). In my opinion human suffering makes a direct moral appeal, namely, the appeal for help, while there is no similar call to increase the happiness of a man who is doing well anyway [Popper, 284].

- It is more important to relieve suffering than to increase (already happy people’s) happiness. We can retain this important intuition (…) by giving more weight to negative welfare than to positive welfare by, for example, incorporating some version of the Priority View in our axiology [Arrhenius, 138].

- Even classical utilitarians admit that in most cases the reduction of suffering should have a higher priority than the promotion of happiness [Fricke, 14]. It is easier to find a consensus on the kinds of suffering to be combated, than on the kinds of happiness to be promoted.

Ethical goals

The positive utilitarian imperative to “maximize happiness” is insatiable, while the negative utilitarian command to “minimize misery” is satiable: no matter how much happiness we have, the positive principle tells us that more would always be better. But the negative principle ceases to generate any obligations once a determinate but demanding goal has been reached: if misery could be eliminated, no further obligation would be implied by the negative principle [Wolf]. Note: Wolf’s statement refers to strict negative utilitarianism (chapter 5.1).

Risk ethics considers chances as well, but the emphasis is on the risks. There is no symmetrical “ethics of chances”.

The existence bias

There is also an asymmetry in favor of happiness, the so-called existence bias [Metzinger 2017, 243] [Metzinger 2009, 280-281]:

People treat existence as a prima facie case for goodness. Longevity is a corollary of the existence bias: if existence is good, longer existence should be better (Status quo bias, Wikipedia).

Except from cases like physical suffering and/or mental depression the existence bias generates a permanent feeling of satisfaction to exist. The capability to forget negative events, to limit compassion and to look optimistic into the future improves a persons’ biological fitness. The majorities’ perception of suffering and risk is accordingly distorted; see The Cultural Evolution of Suffering.

Empathy

Empathy is a psychological concept that describes the ability of one person (the so called observer) to feel in another person (the target). Most contemporary empathy researchers agree that two different aspects of empathy have to be distinguished: the cognitive and the affective aspect [Davis]:

- One speaks of cognitive empathy, if the outcome of an empathic process is that the observer knows what the target feels.

- One speaks of affective empathy, if the observer feels something while perceiving the target

Empathy might be created by mirror neurons in the human brain [Goldstein, 321], i.e. by a function which enables imitation learning and dissolves the barrier between the self and others. It has been speculated that empathy may be an essential part of the cause of moral and social behavior in humans and animals (see e.g. the research of Tania Singer).

Cognitive empathy

The cognitive aspect of empathy is sufficient to justify the Golden Rule (moral impartiality), if the law-maker is conscious, that his role of observer (of suffering) can turn into the role of the target. Cognitive empathy gets support from recent discoveries in biology. There is a close genetic relation between all humans.

On average, in DNA sequence, each human is 99.9% similar to any other human (Human Genetic Variation).

Life stories can be very different although genes perfectly match (see Twin Study). The characteristic of an individual is also formed by the environment and by chance (and not only by genes), but the phenotype and the socially caused differences belie the wide commonalities. There are good reasons to claim that the 0.1% genomic difference and the life story form individuality, but why should the other 99.9% not be an important part of our “self”? Most people consider 99.95% (children) and 99.925% (grandchildren) of their genome to be an essential part of their self. Why not 99.9%? The higher the level of suffering, the more we are all alike, i.e. the peculiarities of an individual’s gene combination and life story become unimportant.

A person can also apply cognitive empathy to him-/herself. It is a cognitive achievement to look into the future and think about one’s destiny. It is possible to consider the person one will be in the future like a different person. In this case the look into the future is similar to an empathic process. As far as the observer knows what the target (in this case the person, that observer will be in the future) feels, it is an example of cognitive empathy. If the person is conscious that his/her “role of observer” will turn into the “role of the target” then the Golden Rule can be applied within the same person.

Not only the person we will be in the future, but also the person we were in the past may appear to us like a different person [Rothman]:

Personalities change. You are not the person you were as a child, or even last year [Young, 29]. Four to eight weeks of psychotherapy and even a single session of consuming magic mushrooms can have a big effect on personality. As a scientific concept, the idea of a “true self” is not tenable [Young, 31].

If an elder person looks at his/her own past self, then

- the difference in time (different life phases, change of physical appearance and character traits) is experienced like

- a difference in space (other persons with different physical appearance and character traits).

The position of the ego becomes relative.

This may lead to the insight that we could be a different person, or any other person and – as a consequence – that the suffering of others is as real and as important as one’s own suffering.

Usually in the morning we wake up and remember our names, our occupation and our plans. We do not question our identity [Hampe 2014, 396].

- In dreams, however, it is not uncommon to have the consciousness of an earlier stage in life or a completely changed kind of consciousness. Dreams are perceived as real as everyday life and sometimes even more intense.

- Some people suffer from a nightly stroke, lose a part of their memory, and wake up as a permanently changed persons. Most of these people feel that they have lost something, but not all of them:

People with retrograde amnesia, for example, can lose memories from before the accident or illness that caused it, while retaining the ability to lay down new memories. They do not feel as if their self has been wiped out [Young, 32].

- People with a dissociative identity disorder feel that they have more than one self, and often cannot control when one of them is activated.

- Some people have memory flashes, about consciousness without an ego, or very early stages of the ego. The development of the self is an awakening from the void.

We have no control over these different kinds of awakening.

The “self” is a transient and contingent phenomenon [Hampe 2014, 403] which – metaphorically spoken – can change, emerge, or end every night.

|

The Other Self

If you awake in the morning and clearly recall the past then you are still the same and your self is secured by its history.

But if you wake up with new eyes and slowly begin to see then you are no more the same and your other self died with its memories.

|

Compassion

Compassion is affective empathy in response to other people’s suffering. The more cognitive empathy is accompanied by affective empathy, the more it controls behavior.

- The closer the relation to the suffering individual, the more affective empathy becomes dominant. The root of compassion is the biological utility function and the corresponding family relations. But the feeling of closeness can also emerge independent of the family. The more intense the suffering of an individual, the less he/she is a competitor, rival or opponent. It is easier to stay emotionally distant; if the victim is self-responsible for his/her suffering, but only up to a certain point. In extreme cases of suffering the judgment prevails, that nobody deserves such a fate. The saying “I wouldn’t wish this on my worst enemy” catches the essence of this phenomenon.

- If the feeling of closeness is lacking, then affective empathy often causes a spontaneous refutation, urging the observer to turn away. We don’t want “something like that” to exist. It disturbs, strikes as unpleasant or frightens.

It is known, that personal experiences of suffering enhance the capability to feel compassion. It is not required though, that these experiences must be exactly the same or have the same intensity as the ones of a victim. Personal experiences of suffering also change the attitude towards one’s own risks. A person who acts against his/her own interests is either not informed or irrational. In the latter case an empathic moral law could be used to protect the person from him/herself. But most people refuse a corresponding restriction of autonomy.

Example: A person sometimes changes his/her character within lifetime in such a way, that he/she seems to be a different person. The “person of age 15” does not much care about the “person of age 50” and smokes e.g. fully conscious of the risk of lung cancer. This lack of compassion within the same person is similar to the one across different persons.

Justice

Would the world become a better place, if we could feel the suffering of others more? That depends on the way empathy is applied. In everyday life empathy is biased and often leads to unjust decisions [Bloom]. If empathy is combined with impartiality, however, then the corresponding decisions do not favor a particular group of people (see Negative Utilitarianism and Justice).

The Open Philanthropy Project proposes radical empathy, i.e. an extension of empathy to all sentient beings. In the past we often discarded major sources of suffering because of our lack of knowledge. Empathy with all sentient beings leads to complex discussions how to weigh and balance human and non-human interests and how to extend the notion of justice to animals [VanDeVeer 1994] [Garner 2013].

Definition of Risk

In order to define risk, one has to define situations like loss, catastrophe or undesirable outcome. Risk can be expressed in terms of financial loss, suffering, risk of dying etc. This definition makes clear, that risk can only be valuated relative to a goal. If not mentioned otherwise in this paper, the term risk relates to suffering.

Definition of Risk-aversion

1) Risk-aversion is

- the preference for a more certain, but lower, expected payoff (e.g. a bank account with a low but guaranteed interest rate).

- opposite to a higher, but less certain expected payoff (e.g. stocks)

For an example see Interactive Tutorial on Risk-Aversion (https://sambaker.com/econ).

The opposite of risk-aversion is risk-tolerance.

2) A person behaves risk-neutral if he/she doesn’t demand a premium (compensation) for risk-taking. The person tolerates risk but doesn’t seek it.

3) A person is risk-seeking if it is attracted to risk, i.e. he/she prefers an investment with a lower expected return but greater risk, to a no-risk investment with a higher expected return. Example: A bungee-jumper pays for risk.

The cognitive aspect of risk-aversion

According to which criteria can we say that we learn something in life? To what extent is the perception of risk in the second half of life “more true” or “more realistic” than in the first half? Is this perception not just a mirror of the personal situation, as in the first half of life? There is undoubtedly a strong part of the evaluation which reflects the current situation. But the evaluations in the second half of life additionally have a comparative and cumulative character. Earlier evaluations can be corrected:

▪ The young people’s phantasy of an unlimited expansion of capacities is gradually corrected. Advice concerning the transience of power and love has no effect on adolescents, but only the experience of personal failure. In the midlife crisis experiences of failure meet the increasing awareness of one’s own limitations.

▪ There are not only transcendent experiences of happiness, but also transcendent experiences of suffering. In traumatic experiences the affected person is offset in a world of nightmares, which cannot be intellectually understood and assessed. The feeling of invulnerability which is inherent to the youthful (and still undefeated) observer is abruptly rebutted in the trauma. The “being out-of-oneself” of pain often induces a strategy of avoidance and a lower-risk way of living. A traumatic experience can change the character of a person even in early youth. But the usual course of things is an increase of traumatic experiences towards the end of life, whereby the world of nightmares slowly becomes real. Risk-aversion grows with negative experiences and – in the course of life – the proportion of negative surprises (accidents, illnesses, loss of close persons etc.) increases relative to the positive ones. As a consequence older people are more prudent than young ones, independent of the initial attitude and the individual sensitivity.

▪ The feeling that life lasts almost indefinitely, that death is far away, is gradually corrected by physical decay. In old age a kind of reversal situation arises as compared to the adolescence. The body, which was a source of joy, becomes a source of suffering. For young people the body procures a feeling of freedom, for old people it becomes a prison. The mind, which is locked in the body, looks for an escape.

|

One experiences happiness as a gift and later realizes that it was a credit.

Author unknown

|

Origin

Antinatalism originates in ancient Indian philosophy. From the Buddhist point of view the creation of egos is simply a misconception [Zimmer 1973, 214-215]. The suffering which is produced by the transience of the ego (aging, illness, death) can only be alleviated by weakening the attachment to the ego. So why create an ego in the first place? Once the ego is created, its perception is distorted by the will to survive. To ask the actual generation if it evaluates life positively is like asking an addict about his/her preference for drugs. Why should we create a state which forces us to interpret suffering in an endurable way? Buddhist and Hindu monks pursue the moral ideal of childlessness. Hindu monks believe that nothing detracts the human soul more from the path of liberation than the birth of a child, a claim that makes sense in the light of (genetic) reincarnation. The ancient Indian doctrine that incarnation is undesirable was taken up by Arthur Schopenhauer, who is considered to be one of the spiritual fathers of antinatalism.

Definition

Antinatalism is the philosophical position that asserts a negative value judgement towards birth. It has been advanced by figures such as Arthur Schopenhauer, Brother Theodore and David Benatar. Schopenhauer, in his essay On the Suffering of the World clearly advocates childlessness.

For Schopenhauer’s direct quote click here.

Similarly, Benatar argues from the hedonistic premise that the infliction of harm is generally morally wrong and therefore to be avoided, and the intuition that the birth of a new person always entails nontrivial harm to that person, that there exists a moral imperative not to procreate (Antinatalism, Wikipedia).

For information about the different versions of antinatalism see [Häyry].

For information on antinatalist movements see:

- Voluntary Human Extinction Movement (VHEMT)

- Antinatalism International (www.antinatalisminternational.com)

Repressed risks

The degree of risk-aversion, the weighting of the risks and the decision-making in procreation are an individual matter and cannot be delegated to an ethical committee. But it is evident that the perception of risks and chances is systematically distorted because the decision to have children is usually taken at an emotional peak of one’s life. From a biological point of view, it makes sense to couple procreation with a spontaneous conviction to do the right thing and (at the same time) with a loss of reason and realism.

Deciding for parenthood entails exposing one’s children to the human condition. This means, in particular, that every new life is also sentenced to death. In a state of infatuation it is almost impossible to apprehend what it means to get old and ill, and what it means having to die (see empathy gap). Similarly difficult is the imagination that one’s child could become the victim of an accident, crime, or severe disease. And not only the children, but also the parents are exposed to risk:

- The responsibility to defend one’s children in times of war and social conflict can make it impossible to lead a non-violent life.

- The love for their children makes parents vulnerable to being (emotionally) blackmailed.

- If the children suffer or stray from the right path, then most parents suffer as well.

Finally, the risk that children could become perpetrators (and not only victims) is largely ignored. The aggressive human nature not only threatens fellow humans but also other species and the ecological equilibrium. A small aspect of this aggressive potential is demonstrated by the killing of animals for food (for an example see Blood of the Beasts). An indication of the full potential is given by the List of wars and anthropogenic disasters.

|

We will never experience an acceptable world, for, in an acceptable world, humans do not exist.

|

The Omelas metaphor

Some antinatalists are guided by the intuition that the extreme suffering of a single individual is reason enough to deny the world. In her novel The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas Ursula K. LeGuin describes a city where the good fortune of the citizens requires that an innocent child is tortured in a secret place [LeGuin]. The city stands symbolically for the world community and the child stands symbolically for the innocence of extreme sufferers. The Ones Who Walk Away are the people who deny the world. We will associate them with antinatalists in this paper.

The metaphor suggests that individual happiness is ambivalent. The joy of the majority is at the cost of a suffering minority; one is not possible without the other. There is no doubt that the human suffering in this world is caused by procreation, but the relation is indirect. Parents participate in an immensely complex system of interactions and probabilities. Often a contingent event decides who becomes a victim. As a consequence, participants deny the responsibility for the results of the system – a phenomenon which is also known in the context of structural violence [Galtung]. If the human race were a sympathetic race, it could walk away from Omelas. But the majority is frightened by the imagination of a world without humans and prefers a silent agreement according to which the torture of a few is tolerable [Contestabile, 51]

3.2 Comparison with Ancient Indian Philosophy

In daily life major risks are repressed because the imagination of a constant horrible threat (like accidents, earthquakes, strokes etc.) paralysis all activity. Opinion surveys about happiness [Frey] rely on this repression. But the regularity of daily life is an illusion; the power of contingency is omnipresent [Hampe 2006]. Experiences with contingency might have contributed to the concept of the Hindu Maya, the imagination that we live in an illusory world and that our perception is distorted. The unconscious part of the psyche ignores all risks which are not accessible by the senses.

At the beginning of chapter 2 we mentioned that – seen from Rawls’ Original Position – compassion and risk-aversion are the same. Intentionally or not, this thought experiment has an affinity to the Hindu concept of reincarnation. With respect to the term “veil of ignorance” (an allusion to the Sanscrit “avarana” or “veil of Maya ”) it is allowed to speculate that Rawls was inspired by ancient Indian philosophy. Hindus imagine that a soul which descends into the body comes under the influence of cosmic delusion called Maya. Individual delusion or ignorance creates ego-consciousness. Rawls’ individual behind the veil of ignorance corresponds to a Hindu soul, waiting for incarnation.

Hinduism and Buddhism developed reincarnation ethics based on the knowledge around the 6th century BC. Recent discoveries in biology have shown that a contemporary interpretation of reincarnation could bring the concept back to life. Ever since the close genetic relation between all sentient beings is known, compassion and risk-aversion seem to be more rational and reincarnation less counter-intuitive. If the idea of individual souls waiting for reincarnation is replaced by the idea of the gene-pool, then nothing is left which couldn’t be reconciled with a scientific world view. Obviously, Rawls’ concept can be interpreted as a reincarnation metaphor if the term reincarnation addresses genes and not individual souls. The same 99.9% of the human genome are incarnated over and over, see Secular Buddhism and Justice.

Under the conditions of reincarnation, we would attempt to preserve our multigenerational experience in order to make an undistorted estimation of risks and chances. We can consider the reincarnations like a continuous stream of experiences similar to the different stages in the life of an individual. Because of the asymmetry between suffering and happiness (chapter 2.1) we would – if it were possible to preserve experience – become increasingly risk-averse. In particular, at some point in our stream of experience, we would know traumatic suffering not only intellectually but also emotionally. Traumatic suffering leaves irreversible traces in the memory, similar to irreversible physical injuries [Wenzel]. After many reincarnations (which can be seen as a learning process), we would come to the conclusion – in accordance with Hinduism and Buddhism – that the best decision is to quit the wheel of reincarnation. In the words of Jean Améry: “Anyone who has suffered torture will never again feel at home in this world”.

In real life, however, the transfer of experience between the reincarnations is prevented by death. The destruction of memories is a destruction of experience and a destruction of risk-aversion. Most cultures do not have a long-term memory about suffering. For today’s generation the memory of past wars, for example, is more intellectual than emotional. The suffering created by epidemics and natural catastrophes is forgotten as quickly as the fate of extremely suffering individuals. Optimism awakes again with each new generation. Retreat-oriented ways of living and the ethical ideal of childlessness are accordingly associated with irrationality or depression.

3.3 Comparison with Person-Affecting Views

Terminology

According to utilitarian theory there is a level of welfare, at which the value of a life is neutral [Broome 2004, 142]. Above this level a life is worth living, below it is not worth living. A neutral life has the value zero on the hedonic scale [Broome 2004, 257].

In this paper we use the term positive welfare as a synonym for life satisfaction, well-being, quality of life and happiness. The term negative welfare stands for uncompensated suffering [Fricke, 18] and is a synonym for lives not worth living.

Person-affecting views

In classical utilitarianism the creation of happy people has moral value. As far as happiness can be guaranteed, there is a moral obligation to create it.

Person-affecting views maintain that there is no moral obligation to have children, because unborn children do not suffer from missed chances [Narveson] [Caviola, 27]. Childlessness is only morally relevant if it affects existing persons.

Person-affecting views can be seen as a revision of total utilitarianism in which the "scope of the aggregation" is changed from all individuals who would exist to a subset of those individuals (Person-affecting views, Wikipedia).

Asymmetric person-affecting view

In the symmetric person-affecting view, the well-being and probable misery of possible people don’t count as a reason to bring them into existence. Having children is morally neutral. In the asymmetric person-affecting view

- the well-being of possible people doesn’t count as a reason for bringing them into existence. However, their probable misery counts as a reason for not bringing them into existence [Arrhenius, 115].

- Adding a life with positive welfare neither makes a population better nor worse, other things being equal. Adding a life with negative welfare makes a population worse, other things being equal [Arrhenius, 137].

Also see Asymmetric Person-Affecting Views, Wikipedia

In other words [Benatar]:

- The absence of pain is good

- The absence of pleasure is bad only if somebody is deprived of that pleasure

As a consequence:

- We are responsible for the probable misery of future people, but

- we have no moral duty to procreate because unborn people do not suffer from missed opportunities.

Diagram from the internet (Author unknown)

Since positive welfare doesn’t count in new lives and negative welfare cannot be excluded, the asymmetric person-affecting view demands to abstain from procreation. For that reason it can be seen as a possible theoretical foundation of antinatalism.

The asymmetric person-affecting view deviates from ancient Indian philosophy. Hindus and Buddhists strive to leave the cycle of reincarnation (except for metaphysical reasons) because the expected suffering of future people surpasses happiness, and not because the future happiness has no value.

Population ethics

The asymmetric person-affecting view emphasizes that the situation of an existing suffering person doesn’t get better by adding happy people to the population. Disregarding the happiness of possible people, however, creates a problem in the comparison of populations:

Is it counter-intuitive to claim that, other things being equal, we make a population better by creating an extra person with very high welfare? Consider the following two populations: “A” consists of a number of people with very low positive welfare and “B” is a population of the same size as “A” but made up of people with very high welfare. If we have a choice of either adding the A-people or the B-people then the Asymmetry Principle claims that “A” and “B” are equally good or incomparable [Arrhenius, 137]

I think that one of the motivating ideas underlying Asymmetry has to do with the weight of suffering: It is more important to relieve suffering than to increase (already happy people’s) happiness. We can retain this important intuition underlying Asymmetry (perhaps the main intuition underlying it) by giving more weight to negative welfare than to positive welfare by, for example, incorporating some version of the Priority View in our axiology. This move yields that in general, we have a stronger moral reason to refrain from creating people with negative welfare, or to increase the welfare of existing suffering people, than to create people with positive welfare, but it avoids the disagreeable implications of the Asymmetry Principle. [Arrhenius, 138]

We will investigate the Priority View in chapter 4 of this paper.

Empirical data

In an empirical study participants were presented with a scenario about a couple considering whether to have another child. Participants were asked to rate whether the hypothetical facts that the child’s life would either be full of suffering or full of happiness were morally relevant to the couple’s decision. Nearly 75% of participants thought that both facts are morally relevant. Only 15% of participants supported a strict asymmetry and thought that only the fact about suffering but not the fact about happiness was morally relevant. This could be seen as evidence that most people do not endorse the asymmetry [Caviola, 9, 31] [Spears].

It seems that the asymmetric person-affecting view is not the best theoretical basis for antinatalism. Following some more attempts to shatter the foundations of antinatalism:

Classical utilitarianism

According to surveys on subjective life satisfaction the majority of people are satisfied with their lives. From a classical utilitarian perspective the antinatalist ideal of a world without humans is therefore irrational. For a reply to this argument, see The Denial of the World from an Impartial View and Is There a Predominance of Suffering?

Some philosophers claim that – without the perspective of future happiness – humanity would fall in a deep depression and that “we” are therefore forced to think positively [Scheffler]. For an answer to this argument see [Hampe 2015].

Depression

Some psychologists argue that antinatalism cannot be taken seriously because its proponents have a mood disorder that is warping their view of reality. Curiously, though, having some degree of depression could help an individual to better see how things really are, which is surely one of the main – if not the primary – aims of philosophy. Depressive realism is a hypothesis developed by the psychologists Lauren Alloy and Lyn Yvonne Abramson in 1988; it essentially states that depression may afford an individual with a more accurate view of the world than the non-depressed (…). In terms of the evidence for and against depressive realism, some studies have indeed found that mild-to-moderate depressed participants were more accurate in their perceptions and judgements than their non-depressed counterparts (On Antinatalism and Depression, by Sam Woolfe).

The will to survive

A major argument against antinatalism is the biological will to survive. Parents imagine that the life of their children and grandchildren is somehow a continuation of their own life. Dynasties resemble pocket-size utopias. The individuals are comforted by the idea that their characteristics will survive within the dynasty. But is that true?

Your child, even your grandchild may bear a passing resemblance to you, perhaps in a talent for music, in the color of her hair. But as each generation passes the contribution of your genes is halved. It does not take long to reach negligible proportions [Dawkins].

The idea to preserve an individual’s characteristics by building a dynasty proves to be irrational. If we consider the ego as a project in which we have to invest, then we must conclude that this project has no future. Presently it seems that even the characteristics of humanity as a whole will become meaningless. Artificial intelligence may soon surpass and replace humans [Rees, 86].

Rawls’ intergenerational justice

Let us assume that the non-existence of humanity is morally preferable. Why should the actual generation get the task to annihilate the immense will to survive built up by all previous generations? The task to eliminate all future risks cannot be burdened to a single generation. Even if we adopt the moral demand for risk-reduction, the task of the actual generation is to reduce risk and not to completely eliminate risk.

Example: Consider the family like a pocket size population. In this case a population policy for reducing risk could be the following:

- If the possible parents do not severely suffer from childlessness, then they should abstain from procreation, because the next generation might suffer more from childlessness than the possible parents of the actual generation.

- It is defensible to have a child, if at least one of the parents suffers severely from childlessness.

- It is defensible to have two children, if both parents suffer severely from not having an additional child.

Since this strategy leads to a long-term decrease of the population size, it reaches the antinatalist goal by a morally less demanding route.

The Omelas metaphor

The antinatalist interpretation of Ursula LeGuins novel mentioned in chapter 3.1 can be criticized as follows:

If the suffering child is given the highest moral priority, then it becomes a moral dictator and creates a kind of inverse injustice [Contestabile, 51-52]. The majority of the citizens should suffer from childlessness in order to avoid the suffering of a single person. The antinatalist reply here is that the suffering caused by childlessness can in no way be compared to that of torture and therefore – despite the greater number of people affected – cannot serve as a justification.

Another criticism says that it is theoretically possible to improve the situation of the Omelas child. Arguments for and against such an improvement can be found in The Cultural Evolution of Suffering. Antinatalists, however, do not participate in speculations about the future. For them the City of Omelas is discredited once and for all. A system (respectively the laws of nature) that produced the history of torture, the Holocaust and the Hoeryong camp cannot be trusted and must be denied, regardless of its hypothetical merits in the future.

Dilemmas

Because of the “moral dictator argument” the Omelas metaphor can be seen as a moral dilemma (see www.friesian.com/valley/dilemmas.htm). Philosophical antinatalists argue that there is something inherently unacceptable in the construction of the world because moral dilemmas are unavoidable. Here some more examples:

- Animal testing: The stronger species avoids suffering at the cost of the weaker species.

- The torture of the mad bomber. A madman who has threatened to explode several bombs in crowded areas has been apprehended (…). The authorities cannot make him divulge the location of the bombs by conventional methods (…). In exasperation, some high-level official suggests torture (www.friesian.com/valley/dilemmas.htm).

- The atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki demonstrate that the arms race leads to an ever more insane destruction. There is no escape from this race for promoters of justice. The non-violent fighters for justice succumb to the violent representatives of injustice.

- The attempt to circumvent conflicts by leading a retreat-oriented life is also open to challenge. It is problematic to live a secluded and passive life when one could actively help (see the drowning child analogy). This attempt to avoid dilemmas ends in a new dilemma.

Finally, two well-known ethical dilemmas:

- The biological sense of life rewards having children despite of well-founded antinatalist arguments.

- The biological sense of life creates the fear of death even in cases where death could liberate from extreme suffering.

|

This world cannot be recommended to a child, ......... if you love the child.

Antinatalist blog

|

|

Self-defeat

The major antinatalist argument is the prevention of suffering. However, since antinatalists eliminate themselves (by definition) the percentage of compassionate people decreases in the remaining population. The opponents of antinatalism are (in the average) better able to repress risk, better able to forget painful experiences and less bothered by compassion. Consequently, suffering tends to increase in the remaining population.

Antinatalists reject the responsibility for this undesirable outcome. It is not in their power to persuade everyone of their moral view, a view that would definitely end human suffering. The idea of leaving the antinatalist movement and creating a dynasty of compassionate people is not realistic either. There is no guarantee that the motivation to reduce suffering survives. With each generation the compassionate parent’s genes fade away; the environment and the life stories change. And even if there were such a guarantee, it would be morally questionable. Antinatalists refuse to force children participating in a project with immense risks and uncertain outcome. Concerning the risks and the uncertainty see The Cultural Evolution of Suffering.

Theoretical foundation

We have seen that the asymmetric person-affecting view is not a convincing basis for antinatalism (chapter 3.3). Following two other consequentialist theories, which question the moral value of procreation:

1. Prioritarianism with negative totals (chapter 4).

2. Negative Utilitarianism (chapter 5)

Definition

Prioritarianism or the Priority View is a view within ethics and political philosophy that holds that the goodness of an outcome is a function of overall well-being across all individuals with extra weight given to worse-off individuals. Prioritarianism thus resembles utilitarianism. Indeed, like utilitarianism, prioritarianism is a form of aggregative consequentialism; however, it differs from utilitarianism in that it does not rank outcomes solely on the basis of overall well-being (Prioritarianism, Wikipedia)

Prioritarianism preserves the efficiency of utilitarianism and a particular concern for those badly off. It does not exclusively focus on total welfare but also accounts for an unjust distribution [Lumer].

Prioritarianism models the asymmetry between suffering and happiness (chapter 2.1).

The moral value of an improvement in well-being matters more, the worse off people are [Broome 2004, 224] [Lumer, 6].

Fig.1

Prioritarianism is not vulnerable to the so-called Leveling Down Objection. According to this objection it cannot in any respect, be better to increase equality when this means lowering the welfare of some and increasing the welfare of none (Prioritarianism, Nils Holtug).

Prioritarianism has two aspects

1. In a history of social welfare happy people get less moral weight than suffering people. The devaluation of happiness is a measure for sympathy [Lumer, 2] respectively compassion. Different prioritarian welfare functions correspond to different degrees of compassion (chapter 2.2).

2. In decisions under uncertainty, happy outcomes are morally devaluated relative to unhappy outcomes. The devaluation is a measure for risk-aversion (chapter 2.3).

For a representative in the Original Position the devaluation is the same in both cases.

- The measure for compassion in histories corresponds to

- the measure for risk-aversion in decisions under uncertainty.

The devaluation of happiness (respectively the priority of the avoidance of suffering) represents a consensus on compassion and risk-aversion.

The prioritarian intuition

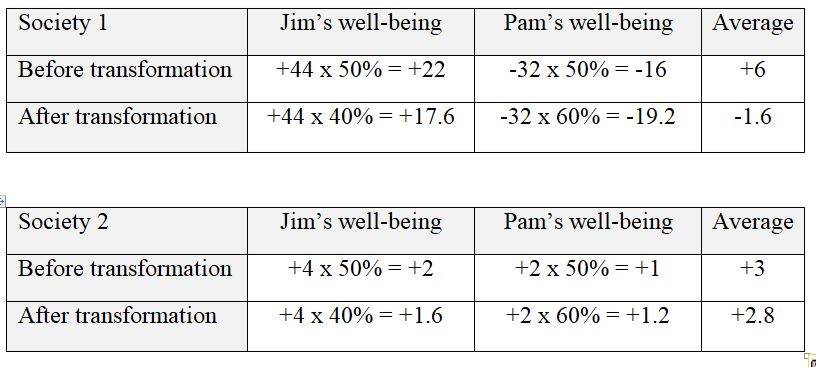

Imagine a two-person society: its only members are Jim and Pam. We compare the following two histories:

- In society 1, Jim’s well-being level is +44; Pam’s is -32; overall well-being is +12.

- In society 2, Jim’s well-being level is +4; Pam’s is +2; overall well-being is +6.

Prioritarians would say that society 2 is better or more desirable than society 1 despite being lower than society 1 in terms of overall well-being. Bringing Pam up by 34 is weightier than bringing Jim down by 40. Prioritarianism is arguably more consistent with commonsense moral thinking than utilitarianism when it comes to these kinds of cases, especially because of the prioritarian’s emphasis on compassion. It is also arguably more consistent with common sense than radical forms of egalitarianism that only value equality (adapted from Prioritarianism, Wikipedia).

The prioritarian transformation

How can we valuate social welfare in such a way, that society 2 in above example is preferable to society 1? (Social welfare is the accumulated well-being of all members of the society).

Roughly, the idea is that we should maximize welfare, but gains in welfare matter more, the worse off people are, and losses in welfare matter less, the better off people are [Arrhenius, 110]. Another way to express this intuition is to say that the marginal value of welfare is diminishing [Arrhenius 2000, 106]. One can achieve this result by applying a strictly increasing concave transformation to the numerical representation of people’s welfare before summing them up [Arrhenius 2008, 8]

Strictly increasing concave transformation means the following: The lower the welfare of an individual is relative to the others, the more weight it gets in the accumulation and vice-versa [Holtug, 13].

1. If the total of all weights (percentages) equals 100%, then the result is a weighted average (see example 1)

2. If the weight of a neutral life is =1, the weight of happy lives >1 and of suffering lives <1, then the result is a weighted total (see example 2)

Example 1

Let’s assume well-being can be in the range from -50 till +50. Moral weight is assigned as follows:

Prioritarian transformation, following the Prioritarian intuition above:

After the transformation society 2 is clearly preferable to society 1.

Example 2

Let’s assume well-being can be in the range from -60 till +60. Moral weight is assigned as follows:

If we apply this weighting function then positive values greater than 20 are cut into half and negative values smaller than -20 doubled:

- In society 1, Jim’s well-being becomes +44 / 2 = 22, Pam’s -32 x 2 = -64 and overall well-being -42.

- In society 2, overall well-being is unchanged +6, because the values are in the neutral range.

Again, after the transformation society 2 is clearly preferable to society 1 (see Fig.2):

Fig.2

4.2 Comparison with Utilitarianism

Comparison with classical utilitarianism

1. In the area of distributive justice (distribution of economic welfare) prioritarianism cannot yield negative totals. In this context prioritarianism represents an asymmetric (compassionate, risk-averse) kind of welfare maximization.

2. In the context of general welfare, however, it is possible to

- decrease the moral value of the happy majority and to

- increase the moral value of the suffering minority

in such a way, that total welfare turns negative (as in the middle of Fig.2). If total welfare turns negative, then the maximization of happiness turns into a minimization of suffering (which is the topic of our paper).

The following picture shows a simplified population, with a happy majority and a suffering minority:

- Classical utilitarianism: The suffering of the minority is compensated by the happiness of the majority, so that total welfare is positive.

- Prioritarianism: The application of a weighting function turns total welfare negative.

Fig.3

Rationality

Intuitions regarding global welfare are controversial:

- The majority thinks that happy people can easily outweigh the suffering of a minority (Fig.3, left hand side). Surveys like the OECD Better Life Index, Satisfaction with Life Index, Where-to-be-born Index, World Happiness Report report persistent happiness on earth.

- A minority does not share this intuition (Fig.3, right hand side):

Ancient Indian predecessors of antinatalism maintained that our everyday perception is distorted; see Negative Utilitarianism and Buddhist Intuition. Philosophical mentors of antinatalism like Arthur Schopenhauer, Philipp Mainländer and Emil Cioran suggested that global welfare is negative.

Who is closer to a realistic view?

- Analytical arguments for a negative global welfare can be found in The Denial of the World from an Impartial View.

- Empirical arguments can be found in Is There a Predominance of Suffering?

From a strictly hedonic perspective a world without humans is preferable to a world with negative total welfare. The efficacy of antinatalism in such a scenario will be investigated in chapter 5.

Comparison with Broome’s utilitarianism

Axiomatic defenses of utilitarianism relying on expected utility theory [Harsanyi, 1955] [Broome, 1991] offer a surprising objection to prioritarianism: the distinction between an amount of good (life satisfaction, well-being, happiness) and how this amount counts is meaningless. Instead of applying a weighting function, compassion and risk-aversion can be expressed by the metric of the hedonic scale.

Broome maintains that an appropriate metric makes the priority view obsolete.

If the priority view should turn out to be untenable, that would not be the failure of a substantive view that the good of worse-off people deserves priority. It would simply be because we have no metric for a person’s good that is independent of the priority we assign it [Broome 1991, 222].

Prioritarianism is not an adequate way to understand fairness [Broome 2004, 39] [Broome 1991, 34-35].

Moral betterness is represented by the unweighted total of people’s well-being [Broome 2004, 137] [Harsanyi, 1974].

Prioritarianism is an adequate theory for the distribution of income, resources or other material things, but not for well-being [Broome 1991, 221-222].

- Broome emphasizes that a person’s good can only be a relative value [Broome 1999, 162-170] and that this information is not captured by the point scales used in surveys on subjective life satisfaction. The relative value mirrors the asymmetry between happiness and suffering (chapter 2.1) and must be assessed separately. For an example of such an assessment see [Caviola].

- Prioritarians, in contrast, think that the surveys on subjective life satisfaction measure absolute values, like the pain intensity in an MRI scan [Hamzelou] or the income of a tax payer. Consequently, they make a distinction between the amount the good (in our context: life satisfaction) and how this amount counts (the priority given to each level of life satisfaction).

The assumptions and the terminology of the two theories are different, but the functionality is the same. Empirical studies about the asymmetry between happiness and suffering [Caviola] can therefore be seen both

- as a basis to construct a utilitarian metric or

- as a basis to construct a prioritarian welfare function

- If prioritarianism can be replaced by utilitarianism in general, then

- prioritarianism with negative totals can be replaced by negative utilitarianism in particular (chapter 5)

- In prioritarianism compassion and risk-aversion are expressed by a non-linear weighting function.

- In negative utilitarianism compassion and risk-aversion are expressed by a non-linear hedonic scale.

A different question is, if suffering and happiness can be mapped to a symmetric, linear scale at all. Possibly classical utilitarianism (which stands for risk-neutrality) works with a distorted, unrealistic hedonic scale (see paragraph Rationality above). If that is true, then negative utilitarianism may prove to be risk-neutral instead of risk-averse.

Technical prioritarianism

It is difficult to give precise content to the prioritarian claim. Over the past few decades, prioritarians have increasingly responded to this ‘content problem’ by formulating prioritarianism not in terms of an alleged primitive notion of quantity of well-being, but instead in terms of Von Neumann-Morgenstern utility [Greaves].

In decisions under uncertainty, the devaluation of happy outcomes is a measure for risk-aversion (chapter 2.3). If the decision about the goodness of outcomes conforms to expected utility theory, then we speak of Technical Prioritarianism.

The basic intuition of “priority to the worse off” provides no support for Technical Prioritarianism: qua attempt to capture that intuition, the turn to von Neumann-Morgenstern utility is a retrograde step [Greaves].

John Broome thinks that Technical Prioritarianism can be replaced by utilitarianism (chapter 4.2). Following some solutions to the “content problem” that do not depend on expected utility theory:

Commensurability

There are objections to quantifying, measuring, or making interpersonal comparisons of well-being, that strike against most if not all forms of aggregative consequentialism, including prioritarianism (Prioritarianism, Wikipedia)

If decisions are to be taken between incommensurable values (e.g. between the annoyance of car drivers and the avoided suffering by a decrease of the speed limit) then these values must be made commensurable by a normative act. The best way to legitimize this normative act is a referendum.

The weighting function

Another objection to prioritarianism concerns how much weight should be given to the well-being of the worse off (Prioritarianism, Wikipedia)

Again, the problem can ideally be solved by a referendum, for example in the acceptance or rejection of progressive tax tables. This is indeed practiced in Switzerland. For decisions in smaller groups an opinion poll could deliver the basis for designing the weighting function [Caviola] [Lumer].

Can a large number of people with a mild headache outweigh the torture of a single person? In utilitarianism this problem is known under the term Negative Repugnant Conclusion [Broome 2004, 213-214]. In prioritarianism the weighting function can be designed in such a way, that this kind of compensation is impossible. The aggregated mild headache increases linearly with the number of persons and is limited; the weighing function can be exponential [Lumer]. For information about the compensation of quality by quantity see Population Ethics – A Compromise Theory.

Population ethics

Utilitarianism and prioritarianism are vulnerable to the so-called Repugnant Conclusion. For a solution to this problem see Population Ethics – A Compromise Theory.

The levelling down objection

The levelling down objection says that there is no gain by lowering the well-being of the better off, just to make them more equal to the worse off. Ingmar Persson argues that prioritarianism – a central rival to egalitarianism – is also subject to the leveling down objection:

In the leveling down situation [. . .] there is a reduction of the sum of benefits since the better off lose something, and the worse off gain nothing. But the average moral value of benefits goes up because it is the benefits with the lowest such value that are removed, i.e., the benefits which make some better off than others [Persson 2013, 4]

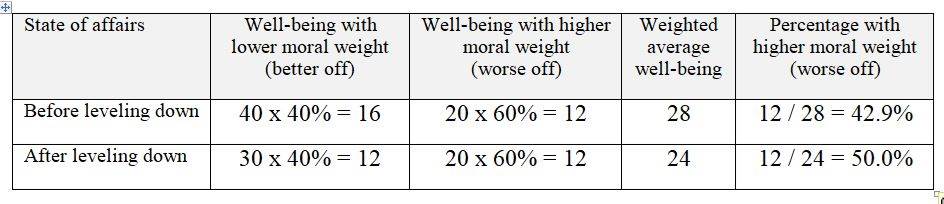

Example:

(instead of Persson’s term benefit, we use the term well-being)

We assume that there are two persons in a mini population: the better off with well-being 40, the worse off with well-being 20.

Leveling down means, in our example

- that the well-being of the better off (40) is reduced to 30 and

- that well-being of the worse off (20) remains unchanged.

Prioritarian transformation:

In above table we see that

- after the leveling down the weighted average well-being goes down (col.4)

- but the percentage of the higher moral weight goes up (col.5) and therefore also the average moral weight.

Persson’s objection fails, because his argument turns on increases in measures in “leveled down states” that have no value on the prioritarian view [Weber, 1, 21].

Persson mixes up moral value and moral weight. He writes:

“…. The average moral value of benefits goes up because it is the benefits with the lowest moral value that are removed” [Persson 2013, 4].

It is the well-being with the lowest moral weight, however, (not moral value) that is removed. As a consequence, the average moral weight (not moral value) goes up. In our example the moral value is measured by the weighted average well-being (col.4).

For more information on the defense of prioritarianism see [Adler].

Definition

Negative utilitarianism (NU) is an umbrella term for all forms of utilitarianism, which model the asymmetry between suffering and happiness [Fricke, 14].

NU includes concepts that

1. assign a relative priority to the avoidance of suffering: moderate NU

2. assign an absolute priority to the avoidance of suffering: strict NU [Caviola, 5-6, 19]

3. consider non-existence to be the best possible state of affairs: negative preference utilitarianism

For the reasons given in Negative Utilitarianism and Justice, we focus on the moderate NU. The moderate NU is functionally equivalent to prioritarianism. The ethical priority increases with the level of suffering.

- In prioritarianism total welfare can turn negative because of a weighting function.

- In the moderate NU the total can turn negative because of the metric of the hedonisc scale.

If total welfare turns negative, then the maximization of happiness turns into a minimization of suffering (which is the topic of our paper). Concerning the rationality of a negative total welfare see chapter 4.2.

Population ethics

- The most common argument against NU is the world destruction argument, according to which NU implies that if someone could destroy the world instantly and painlessly, it would be his/her duty to do so [Smart]. The totalitarian potential, however, is not a peculiarity of NU, but a characteristic of consequentialism in general [Knutsson]. Philosophers, who recognize this potential as a problem, amend their theory with human rights (as a side constraint of any attempt to improve the state of affairs). Such an anti-totalitarian, suffering-focused ethics corresponds to a political party or movement within a democratic system.

- A movement like VHEMT or Antinatalism International could theoretically persuade people to abstain from parenthood. In practice, however, antinatalism is no realistic option to eradicate humanity. There is only a choice between more or less suffering populations. In such a case the adequate theoretical framework is population ethics, i.e. theories about how to rank populations in virtue of their happiness and suffering. The most common axiologies to compare populations are total utilitarianism and average utilitarianism.

NU metrics

- In total utilitarianism quantity (population size) can outweigh quality (average level of welfare). If a large population with extremely low welfare outweighs a small population with high welfare we speak of a Repugnant Conclusion. A radical solution to this problem consists in disregarding the population size and focusing on the average level of welfare.

- Similarly, if negative total utilitarianism valuates a large population with minor suffering worse than a small population with extreme suffering we speak of a Negative Repugnant Conclusion [Broome 2004, 213]. The analogue solution consists in focusing on the negative average level of welfare [Chao].

Despite its theoretical deficiencies [Arrhenius, 54-57] average utilitarianism is the most popular axiology among welfare economists [Arrhenius, 53]. We will therefore use (negative) averages for comparing populations. For a theoretically sounder (but also more demanding) axiology than total or average utilitarianism see Population Ethics – A Compromise Theory.

In classical utilitarianism and prioritarianism (with positive totals) antinatalism is usually no issue at all. In a world of negative welfare, however, it is a possible strategy to reduce suffering. In the following we examine three scenarios where this strategy doesn’t work:

1. The case where an expansion of the population reduces suffering.

2. The case where a contraction of the population increases suffering.

3. The case where antinatalism doesn’t affect total welfare at all.

Expansion under uncertainty

In Fig.4 the actual population is expanded in a situation of uncertainty:

- The population size is represented by column width.

- The average level of negative welfare is represented by column height. As mentioned above, the moderate NU is functionally equivalent with prioritarianism. The NU averages therefore correspond to the weighted averages in prioritarianism. The most suffering people have the most impact on the average.

Fig.4

The scenarios in Fig.4 correspond to the actual situation because the world population will grow at least until the second half of the 21st century (World Population, Wikipedia). Following an example to illustrate the negative utilitarian view:

a) Optimistic scenario: Long-term sustainability can be reached despite of the current population growth. The growing population with its increasing competition and specialization leads to a boost in the health care sector and eventually to a lower average level of suffering [Ridley]. If cultural evolution is seen as a project which reduces the average level of suffering – where otherwise the status quo would persist forever – and if the success of this project requires a larger number of contributors, then it makes sense to expand the population (middle of Fig.4). Transhumanism and other utopias even claim that suffering will be defeated one day, so that total welfare turns into positive territory.

b) Pessimistic scenario: The growing population leads to a shortage of resources, mass migration, social conflicts, and wars (right hand side of Fig.4).

Most biologists and sociologists see overpopulation as a serious threat to the quality of human life (Human Overpopulation, Wikipedia)

Each new person makes demands on the earth’s resources, leaving less for the rest of us. So, on the average, each new person diminishes the lifetime wellbeing of the rest of us [Broome 2005, 400].

A detailed rationale for optimistic and pessimistic scenarios can be found in The Cultural Evolution of Suffering. According to this investigation the pessimistic scenario is more likely than the optimistic one.

Contraction under uncertainty

In Fig.5 the actual population is contracted in a situation of uncertainty:

- The population size is represented by column width.

- The average level of negative welfare is represented by column height. As mentioned above, the moderate NU is functionally equivalent with prioritarianism. The NU averages therefore correspond to the weighted averages in prioritarianism. The most suffering people have the most impact on the average.

Fig.5

The scenarios in Fig.5 may become relevant towards the end of the 21st century (World Population, Wikipedia). Following an example to illustrate the negative utilitarian view:

a) Optimistic scenario: The shrinking population leads to an abundance of resources, less migration, less social conflicts and, consequently, to an increase in the average level of welfare (middle of Fig.5). Children will feel more welcome in a world with less competition.

b) Pessimistic scenario: The shrinking population leads to a care problem in hospitals and nursing homes and eventually to a lower average level of welfare (right hand side of Fig.5). It is also possible that high-tech cultures require large populations, so that – at some point – the technological standard cannot be maintained.

Possible ineffectiveness

There may be cases where the antinatalist movement doesn’t affect total welfare at all:

- If there is a struggle for food, and the competitive pressure from antinatalists is eliminated, then other families will be able to feed more children.

- A similar mechanism could work for skills. Let us assume an antinatalist disposes of certain skills which correspond exactly to what the environment demands. Then other people with these skills could have more children to fill the gap.

Does the ethical goal to minimize suffering necessarily lead to antinatalism?

If we exclude the eradication of humanity by global voluntary childlessness, then the answer to the above question is not trivial. In theory there are

- cases where an expansion of the population reduces suffering,

- cases where a contraction of the population increases suffering, and

- cases where antinatalism doesn’t affect total welfare at all.

These scenarios, however, are currently not relevant. The growth of the world population – which will continue until the second half of the 21st century – is likely to have more negative than positive effects on global suffering (see The Cultural Evolution of Suffering). Consequently, for adherents of suffering-focused ethics, there are good reasons to promote antinatalism.

1. Ackermann Frank (2004), Heinzerling Lisa, Priceless, On Knowing the Price of Everything and the Value of Nothing, The New Press, New York, London

2. Adler Matthew, Nils Holtug (2019), Prioritarianism: A response to critics, SAGE journals, Politics Philosophy and Economics, Vol.18, Issue 2, 101–144

3. Arrhenius Gustav (2000), Future Generations, A Challenge for Moral Theory, FD-Diss., Uppsala University, Dept. of Philosopy, Uppsala: University Printers

4. Baumeister R.F, Bratslavsky E., Finkenauer C., Vohs K.D. (2001), Bad is stronger than good, Review of General Psychology, Vol.5, 323-370

5. Benatar David (2006), Better Never to Have Been, Oxford University Press

6. Bloom Paul (2016), Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion, Ecco/HarperCollins Publishers, New York

7. Broome John (1991), Weighing Goods, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, Paperback version 1995

8. Broome John (1999), Ethics out of Economics, Cambridge University Press, UK

9. Broome John (2004), Weighing Lives, Oxford University Press, New York, Paperback version 2006

10. Broome John (2005), Should We Value Population?, The Journal of Political Philosophy, Vol.13, No.4, 399-413

11. Caviola Lucius, David Althaus, Andreas Mogensen & Geoffrey Goodwin (2021), Population ethical intuitions, Department of Psychology, Harvard University

12. Chao Roger (2012), Negative Average Preference Utilitarianism, Journal of Philosophy of Life, Vol.2, No.1, 55-66

13. Chauvier Stéphane: A challenge for moral rationalism: why is our common sense morality asymmetric?

14. Contestabile Bruno (2016), The Denial of the World from an Impartial View, Contemporary Buddhism, Volume 17, Issue 1, 49-61

15. Davis Mark H. (1994), Empathy: A Social Psychological Approach, Madison, WI: Brown & Benchmark Publishers.

16. Diener, Ed and Emmons, Robert A. (1984). The independence of positive and negative affect, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 47, 1105-1117.

17. Diener Ed, Lucas Richard, Napa Scollon Christie (2006), Beyond the Hedonic Treadmill, Revising the Adaptation Theory of Well-Being, American Psychologist, May–June, Vol.61, No.4, p.305–314

18. Fischer Shannon (2016), What are you worth?, New Scientist, 22 October, 28-33

19. Frey Bruno, Stutzer Alois (2001), Happiness and Economics, University Presses of CA

20. Fricke Fabian (2002), Verschiedene Versionen des negativen Utilitarismus, Kriterion Nr.15, 13-27

21. Galtung, Johan (1969), Violence, Peace, and Peace Research, Journal of Peace Research, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 167-191

22. Garner Robert (2013), A Theory of Justice for Animals, Oxford University Press, New York

23. Goldstein Bruce (2007), Sensation and Perception, Wadsworth

24. Greaves Hilary (2016), Antiprioritarianism, University of Oxford

25. Häyry Matti (2023), Confessions of an Antinatalist Philosopher, Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 1–19

26. Hampe Michael (2006), Die Macht des Zufalls, Wolf Jobst Siedler Verlag, Berlin

27. Hampe Michael (2014), Die Lehren der Philosophie, Suhrkamp

28. Hampe Michael (2015), Kein Big Bang, Die Zeit, Nr.29

29. Hamzelou Jessica (2010), The scanner that feels your pain, in New Scientist, 6 March, p.6

30. Harsanyi, John (1955), Cardinal Welfare, Individualistic Ethics, and Interpersonal Comparisons of Utility, Journal of Political Economy 63 (4): 309–321.

31. Harsanyi John (1974), Non-linear Social Welfare Functions or Do Welfare Economists have a Special Exemption from Bayesian Rationality?, University of Bielefeld, Germany

32. Holtug Nils (2004), Person-affecting Moralities, in The Repugnant Conclusion, Essays on Population Ethics, Kluwer Academic Publishers

33. Knutsson Simon (2021), The Word Destruction Argument, Inquiry, Vol. 64, Issue 10

34. Johnson Denis (2008), In der Hölle: Blicke in den Abgrund der Welt, Rororo Verlag

35. LeGuin Ursula (1973), The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas, New Dimensions No.3, edited by Robert Silverberg

36. Lumer Christoph (2005), Prioritarian Welfare Functions, in Daniel Schoch (ed.): Democracy and Welfare, Paderborn: Mentis

37. Metzinger Thomas (2009), Der Ego Tunnel, Berlin Verlag

38. Metzinger Thomas (2017), Suffering, the cognitive scotoma, in The Return of Consciousness, 237-262, Editors Kurt Almqvist & Anders Haag, Stockholm, Sweden

39. Mayerfeld Jamie (1996), The Moral Asymmetry of Happiness and Suffering, The Southern Journal of Philosophy, Volume 34, Issue 3, pp. 317–338

40. Narveson, J. (1973). Moral problems of population. The Monist, 57(1), 62-86

41. Popper Karl R.(1945), The Open Society and its Enemies, London, I 9 n.2

42. Persson, Ingmar (2013), Prioritarianism, In International Encyclopedia of Ethics, ed. Hugh Lafollete, Hoboken, Wiley

43. Rees Martin (2003), Our Final Hour, Basic Books, New York

44. Ridley Matt (2015), The Evolution of Everything, Harper, New York

45. Rothman Joshua (2022), Becoming You, New Scientist, 10 October, 20-24

46. Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001), Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and social psychology review, 5(4), 296-320.

47. Scheffler Samuel (2015), Der Tod und das Leben danach, Suhrkamp Verlag, Berlin

48. Sen Amartya (1986), Social Choice Theory, In Handbook of Mathematical Economics, Vol. III, K.J. Arrow & M.D. Intriligator (Eds.), North-Holland, 1073-1181.

49. Sharot Tali (2011), The optimism bias: A tour of the irrationally positive brain, Random House, New York

50. Shriver Adam (2014.1), The Asymmetrical Contributions of Pleasure and Pain to Subjective Well-Being, Review of Philosophy and Psychology, Vol.5, 135–153

51. Shriver Adam J. (2014.2), The Asymmetrical Contributions of Pleasure and Pain to Animal Welfare, Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, Volume 23, Issue 02, 152-162

52. Shulman Carl (2012), Are pain and pleasure equally energy-efficient?

53. Smart R.N. (1958), Negative Utilitarianism, Mind, Vol 67, No 268, 542-543, available from www.utilitarianism.com/rnsmart-negutil.html

54. Smith Adam (1759), Theorie der ethischen Gefühle, Felix Meiner Verlag, Hamburg, 2004

55. Spears, D. (2019). The Asymmetry of population ethics: experimental social choice and dualprocess moral reasoning. Economics & Philosophy, 1-20

56. Stefan Cornelia (2017), Homo Patiens, A socio-philosophical concept, Ph.D.Thesis Nr.726023, Università degli studi dell’Insubria, Italy

57. Szasz, T.S. (1957), Pain and Pleasure – a study of bodily feelings, Basic Books Inc., New York

58. Young Emma (2017), Your True Self, New Scientist, 22 April, 29-33

59. Keown, Damien (1992), The Nature of Buddhist Ethics, New York, Palgrave.

60. VanDeVeer Donald (1994), Interspecific Justice, in The Environmental Ethics and Policy Book, edited by Donald VanDeVeer and Christine Pierce, Belmont, Wadsworth, 179-193

61. Verhaeghen Paul (2015) Good and Well: The Case for Secular Buddhist Ethics, Contemporary Buddhism, 16:1, 43-54

62. Weber Michael (2019), The Persistence of the Leveling Down Objection, Erasmus Journal for Philosophy and Economics, Vol.12, Issue 1, 1–25.

63. Wenzel Thomas, H.Griengl, T.Stompe, S.Mirzaei, W.Kieffer (2000), Psychological Disorders in Survivors of Torture: Exhaustion, Impairment and Depression, Psychopathologie, Psychopathology, 33(6), 292-296